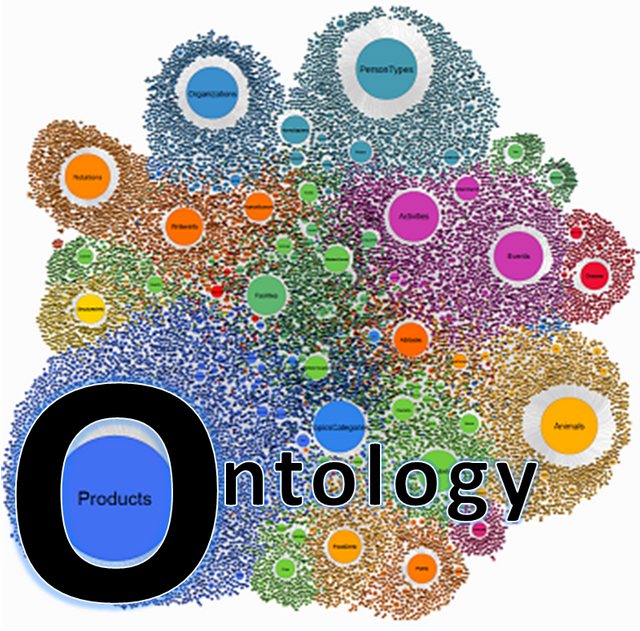

Understanding The Basic Concepts of Mind and Ontology

Image Source

The world gives off an impression of being made of many things. However we know from perception that nature frequently shows the capacity to make variations from a theme. In this manner, it is sensible to ask whether the evident assorted variety of things around us mirrors a hidden themes, that are less, complex, more universal, and more fundamental. When this approach is acknowledged, the conspicuous questions are these : How many such themes are recommended to exist? What is the nature of the hidden themes? How would they identify with each other and to the evident assorted variety of the ordinary world? Such a request is frequently viewed as an essential point of metaphysics.

Since the time of the ancient Greeks, "How many?" has been a fundamental ontological question. Philosophers, generally, have looked for theories in which the plurality of things is reducible to minor variations from one or a couple of fundamental themes, principles, or elements. Regularly an early Greek arche was a substance or some likeness thereof, so a much of the time made inquiry was "What number of substances constitute the whole of reality?" The responses to this question typically fall into two general groups: those proposing one fundamental substance and those proposing two or more substances.

Monist theories date from the most punctual days of philosophy, when Thales held the view that everything was a form of water. The Eleatic philosophers Anaximenes and Anaximander were monists, as were Parmenides and Heraclitus. After the time of the early Greeks, monist ontology turned out to be very uncommon. For a few centuries after the ascent of Christianity, the soul was viewed as real and as unmistakable from the body, and dualist and pluralist philosophies overwhelmed. Not until the Renaissance, when Girolamo Cardano, Giordano Bruno, and Benedictus Spinoza enunciated their systems, did the monist view again end up plainly unmistakable.

Image Source

In the 1700s, the theories of dynamism and energeticism started to build up a scientific reason for monism, making ready for the "mass monism" that came to overwhelm the Western worldview. Pluralist cosmologies started with Anaxagoras' view of the world as made up of bunch sybstances, "infinite in number." Empedocles, another early pluralist, considered all things as made out of four components working in conjunction with two all-encompassing forces, Philotes and Neikos. In the Middle Ages, Paracelsus contended that all things were made out of sulfur, mercury, and salt.

Afterward, Leibniz and James pushed pluralistic views of the universe. More normally, however, philosophers restricted to monism thought about less complex pluralist plans, with just two fundamental substances. Such ontological dualism started with Plato, for whom the genuine reality was the realm of the Forms and the secondary reality was the ordinary "realm of phenomena". The Christian worldview separated reality amongst earthly and heavenly realms, the former the domain of the body and the last of the soul or mind.

This division was fortified by Descartes' refinement between the res extensa and the res cogitans. It was additionally upheld by theories, pushed by Newton and others, that the universe was a law-driven, mechanistic system, as indicated by these theories, mind or soul was verifiable but then clearly not material and accordingly was a different part of reality.

The theory of evolution and the secularism of the twentieth century had a tendency to undermine this duality, driving many contemporary thinkers to a materialist monism as indicated by which mind is a reducible or subordinate substance. However the nonappearance of a persuading theory regarding monism, consolidated much of the time with religious beliefs and intuitive feelings, has kept the idea of ontological dualism alive.

Image Source

Another fundamental question is that of the historical nature of mind: Over the course of universal evolution, how and when did mind become? It appears to be certain that either mind in the most general sense has dependably been present in the universe or else it appeared. The first view is panpsychism, the second is emergentism. Nearly all present-day philosophers of mind are emergentists, who expect that mind developed sooner or later in evolution. Usually, notwithstanding, they don't address the question of how such development is possible, and they don't recognize that one need not accept this.

The question of emergentism is vital to any sufficient theory of mind. Each theory ought to expressly recognize its standpoint on this question. On the off chance that it is an emergentist theory, it should detail how and under what conditions mind has risen, in the event that it isn't emergentist, it ought to expressly acknowledge the panpsychist extension. A few theories of mind, for instance, Searle's necessity that mind be constrained to biological organisms, join rise in the bigger theory, yet such methodologies presently can't seem to win much acknowledgment.

Most generally one finds a soft middle ground in which philosophers neglect to clearly express their views one way or the other. They appear to realize that an unmistakable and intelligible theory of rise is to a great degree tricky, yet they can't force themselves to embrace the main practical option. The above does not suggest that panpsychism is some way or another fundamentally hostile to emergentist.

Panpsychism can, and in truth nearly dependably does, concede the presence of a huge scope of mental complexities, each new level of complexity expressly developing under some condition. Mind is regularly corresponded to basic or advanced complexity, as new physical forms of being rise, so do new forms of mind. Clearly, for instance, Homo sapiens appeared over some period ever, 10 million years ago there were none of these creatures, and 10,000 years ago there were many. Hence, the exceptionally human form of mind without a doubt developed. However mind as a general wonder may have dependably existed. Analyze mind and another fundamental element, gravity. Gravity is all over, and it has dependably existed.

Image Source

super

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Anyway, we all die. And words will scatter in the wind like ash.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yeah indeed but its much better that somehow we have understood those words.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Interesting post.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit