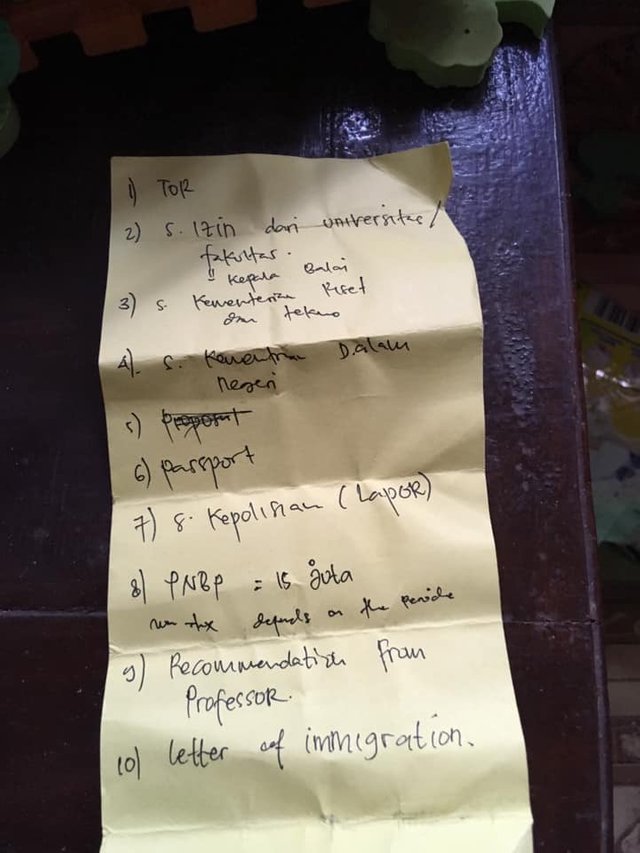

My experience in June can be best described in one word: lethargic. Reason being that not much was done in regards to field work that I’ve described in my last blog post. There are several reasons for this but ultimately it comes down to two primary culprits: bureaucracy in Indonesia and the Eid al-Fitr (called “Idul Fitri” in Indonesia) holiday weeks. Due to the latter, my coworkers at WARSI had to take two weeks off to celebrate the holidays with their families. While I stayed for an extended time in a hotel for the first week, I returned to the field office by the second, ignorantly believing that Idul Fitri was over. While this was a mistake on my part, I did wait, hoping to see my coworkers by next week. Unfortunately, it didn’t even end there, as WARSI had to attend a workshop that was coordinated by the National Park Authority. This lasted for the third week of June and then, given the scope of the topics discussed, WARSI had spent another week discussing the outcomes. Thus, essentially terminating any chance I had of making any significant progress last month! No doubt that these increased discussions show how tedious the bureaucratic process is in Indonesia, which brings me to my next point. When I had visited the Authority Office for Bukit Duabelas NP in May, the Director told me that she required seven steps before I was able to do my research freely in the National Park. It was outlined in the paper below.

The List is:

The List is:

- Term of Reference (ToR)

- Recommendation letter from Professor and University

- License from Research Minister

- License from Home Affairs Minister

- Passport

- License from Police

- Money

- Letter of immigration

As you can clearly see, three of the essential requirements were getting licenses from two separate ministries and from the regional police. This I found unnecessary to which my WARSI coworkers had agreed with in subsequent discussions. Indonesia is notorious for its difficulty towards foreign researchers to gain permission to do research. Where it can take many months to get approval from a single ministry. Even keeping this in mind, I was still perplexed by the many requirements that I had to meet. Since then, I found out that there are strict new regulations which requires foreign researchers to gain more permits before conducting their activities. To not do so could lead “offenders” to be imprisoned for up to two years. On top of this, the topic of research needs to be “beneficial for Indonesia”. What this means usually comes down to pure political interests. Due to environmental issues being a very controversial topic for the Indonesian government, it’s not surprising that most conservationists and environmental advocates are against this ruling. If the worst happens, I could see, at least, a few more months passing before I get full approval. Which means, for now, I am unable to enter the BDNP (unless I get a one-day pass for 150,000 RP or US$10.50) and experience the Orang Rimba’s traditional lifestyle as intended. For the time being, WARSI is discussing with the National Park authority to see what I can do.

Interacting with the Orang Rimba

Regardless, I wasn’t going to let my negative experience with bureaucracy affect my time when I’m at the BDNP camp. Since I was at the WARSI field camp for three weeks, I wanted to get to know the Orang Rimba better in the meantime. With myself now able to speak very remedial Bahasa Indonesia, I could make some simple sentences for my daily activities. One Orang Rimba, Bejujung, stood out to me as he had a desire to learn the English language and he wanted me to teach him as much as possible. I did so with the very limited Bahasa Indonesia I knew (I accredit myself but, admittedly, I relied on Google Translate to communicate around half of what I needed to say) and in return I asked for him to teach me the Orang Rimba language. I say “language” but, in reality, what the Orang Rimba have is a different dialect rather than a full-on language. For the most part, the Orang Rimba “language” has the same grammar and word dictionary as Bahasa Indonesia with a few exceptions. Certain words are different for the Orang Rimba, here are several examples: Yes: Iya Nih (Bahasa Indonesia), Ao (Orang Rimba); No: Tidak (BI), Hopi (OR); Water: Air (pronounced Ai-ree) (BI), Ai (OR). Many terms the Orang Rimba have for the local wildlife is also different, Tiger: Harimau (BI), Merego (OR); Elephant: Gajah (BI), Gedjoh (OR); Helmeted Hornbill: Rangkong Helm (BI), Burung Gading (OR). Also, it should be noted that Orang Rimba speak in more pronounced gaps when saying certain words, a phenomenon which linguists have called “Glottal” stops. For example, an Orang Rimba person would say “U’rang” rather than “Orang”. This makes it feel like I’m learning another language at times and I’m not the only one who came to this conclusion. Ramsey Elkholy (2016, pg. 51) during his studies, found it very difficult to learn Bahasa Rimba and it took him many months before he was able to speak it at a fluent enough level. This was despite the fact that he taught himself a good amount of Bahasa Indonesia beforehand (Elkholy, 2016; pg. 6). To top that off, one WARSI employee I conversed with, who’s new to the organization, needed a translator to come to the field with him to understand what the Orang Rimba are saying, and he’s a fluent Indonesian speaker! Suffice to say, this will be quite the challenge for me for the duration of my time here.

Going back to topic, what struck me out about Bejujung more than his desire to learn English was his character. For one, he spoke notably less with the Glottal stops compared to even the other young Orang Rimba at camp, whom themselves were increasingly using more Bahasa Indonesia words. On top of that, he had his hair slightly dyed, with golden streaks appearing on the top of his head. This was something I expect more from the youths in Jambi City or Palembang rather than here at Bukit Duabelas National Park. I found out the reason behind this, Bejujung was one of three Orang Rimba to go to Yogyakarta to be educated on the secondary level (equivalent to High School in the USA) due to exception performance. This was through a new scholarship program set by PT.SAL (an education company) and supported by WARSI.

While outwardly, I congratulated Bejujung for his achievements, it did exemplify an observation I made when I first came here. The Orang Rimba at the WARSI camp are quite accustomed to what is deemed as a more “modern” lifestyle. They frequently wear western clothing, eat meat from domesticated animals (a taboo in traditional Orang Rimba society), regularly drink coffee and tea, and most of the young adults have their own personal smartphones. It became apparent to me that the Orang Rimba at camp were at what the Indonesian Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) has deemed the “residing level” (Prasetijo, 2015; pg. 98). MoSA categorize the Orang Rimba in three primary “levels”: “nomadic”, “half-nomadic”, and “residing”. Whereas the first two levels describe Orang Rimba that retain, at least, parts of their cultural lifestyle, ‘residing’ Orang Rimba are those who are adopting the lifestyle of outsiders and are in the final process of assimilation (Prasetijo, 2015; pg. 98). The most stark moment I had to tell me how assimilated these indigenous peoples were becoming was a conversation I had with a Orang Rimba named Kemetan.

Towards the end of the month, I struck up a conversation with Kemetan and it got to a point where I was asking him about his personal experience as an Orang Rimba person. Our conversation went roughly how it did below:

“Me: Have you faced discrimination as an Orang Rimba by villagers?

Kemetan: No, I haven’t faced any of that.

Me: None at all?

Kemetan: None.

Me: That’s interesting to hear and your experience is quite different from what I’ve read. I want to know, what do you think the Orang Rimba’s future should be.

Kemetan: I think we should live like the villagers and not in the forest anymore.

Me: Okay, but not all Orang Rimba feel this way, right?

Kemetan: No, in fact there’s a lot arguments of where we should move forward.”

To further solidify Kemetan’s transition, he proceeded to show me a picture of a girl on his phone (which he had been on for half of our conversation). She’s a Malay villager whom Kemetan met through Facebook and Instagram and has been dating for a month by the time of our conversation. This mentality from young Orang Rimba is not new and has been going on for some time now. Anne Berta has written of her experience with the older generation who feel that their young people (especially their young men) are spending too much time away from the forest and are not learning the traditional laws or adat (Berta, 2014; pg. 37-38). Given what I’ve seen, it appears that these young Orang Rimba are continuing to defy their elders to potential cultural oblivion. To give a little hope, not all young Orang Rimba feel this way, as a little boy named Gading told me that, despite living regularly at camp, he wants to continue learning the laws of his people and he prefers to be in the forest rather than a village.

Information from the Jungle People

Another noteworthy information I’ve gathered in June was when I talked with Jalo, who is Gading’s father.

Jalo, a man of high status and respect amongst his people, asked me, at first, small questions about myself, as he wanted to know more about me. This elevated when I told him of my goals and overall intentions of being here. Seeing an opportunity, Jalo told me that he feels the Zoning System doesn’t provide enough for their economic well-being. He explained that the Zoning System must include improving the roads, so that the Orang Rimba can have better access to village markets where they can sell their rubber products.

This way, they’ll have more money which they want to use for better education and healthcare. Which Jalo feels the government also seriously neglects. While, at first glance, Jalo’s statement may seem to contradict the complaints his generation have made, it really isn’t considering the Orang Rimba’s circumstance. Since the 1970s, palm oil companies have been grabbing more and more land by categorizing them as Industrial Plantation Forest (HTI), which can be exploited at will for industrial use (Prasetijo, 2015; pg. 106). As a result, the Orang Rimba’s forest home is now too small and restrictive for them all to live a nomadic existence. In fact, only a few Orang Rimba at Bukit Duabelas still live a full nomadic forest-based life (Prasetijo, 2015; pg. 138); the majority switch between a nomadic lifestyle and tending to their Jungle Rubber plantations.

These plantations are what’s giving monetary means to the Orang Rimba and they need it for their daily activities like sending their children to school. While reluctant at first, many older Orang Rimba came to accept the need for education as many of them were perviously taken advantage of by outsiders due to their illiteracy (note the “thumbprint agreements” in my last post). If their children can learn to read and write effectively, then they won’t be taken advantage of in the future. It’s just that the elders want them to maintain their customary laws along with getting better education. It’s the abandonment of the former which causes the generational conflict.

Time in the Forest

Towards the end of the month, being at camp constantly with little physical activities to do was becoming a huge problem. The overall feeling I got was of stagnation and restriction. To the point where I decided to get a day pass from a National Park branch nearby. I was reluctant to buy a day ticket before because I was keen on saving money as I felt I spent far too much in May (you can partly thank my overpriced language course for this). But the stagnant feeling got to me too much by month’s end and I took the chance. Accompanied by an Orang Rimba named Gako, going into the rainforest of Bukit Duabelas was enhancing, giving a calm and tranquil experience which I definitely needed by that point. Seeing the lush and biodiverse forest instantly set me in a better mood but it also saddened me that this type of forest (lowland tropical rainforests), once widespread across the Sumatran central plains, is now restricted to a few protected areas.

Regardless, my day in the forest did end with a visit to a Rumah Godong/Adat, the biggest type of architecture for the Orang Rimba (Kurniawan et al., 2014). Usually built in the middle of clearings for shifting cultivation plots and can last for up to two years, they are used when settling disputes.

On the way back to camp, Gako and I heard the call of a Rhinoceros Hornbill and then we saw it take flight.

It was a great way to end the month. Still, I certainly will keep my ears clear to hear the call of the critically endangered Helmeted Hornbill while I’m here.

Looking Ahead

For now, I’ll have to continue receiving all the items required on the list. As mentioned earlier, WARSI will continue talking with NP Authorities and we’ll see what needs to be done. So far, I have received a letter of recommendation from my professor who’s the head of the Social Science Department at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia (where I’ll be going to for my Master Thesis in the future). As well as the money total of 15,000,000 RP (equivalent to US$1050) needed for my year long stay in Indonesia. Along with my Terms of Reference (ToR) and Passport. It’s the licenses which seems to be the biggest hurdle so far and I am concerned how long they will take to receive. I’m hoping sometime by the end of July but, given how long the bureaucratic process is, I can’t say for certain. But as one of my teachers at Yogyakarta told me when I was late to class one day due to a delayed time at the Immigration Office: “Welcome to Indonesia”.

Work Citation:

Berta, A. E. V. (2014). “People of the Jungle: Adat, Women, and Change among Orang Rimba” (Master's thesis). University of Oslo, Norway.

Elkholy, R. (2016). “Being and becoming: embodiment and experience among the Orang Rimba of Sumatra.” Berghahn Books.

Kurniawan, K.R., Fadhil, M.N., Iasha, M.C., Putranti, N.D., Saifullah, A.B., Hamid, R.A. & Fardani, N.A. (2014). “Architecture of Semi-Nomadic ‘Orang Rimba’ in the Bukit Duabelas National Park Jambi.” University of Indonesia, Indonesia.

Prasetijo, A. (2015). “Orang Rimba: True Custodian of the Forest.”