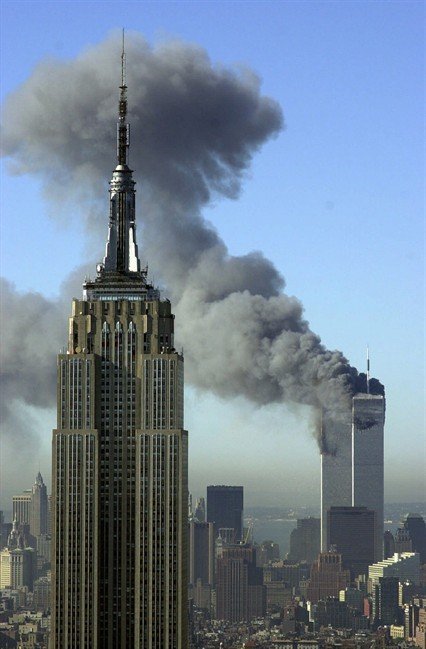

Al-Qaida’s attack on America made Maureen Basnicki a widow and a single mother with two kids, post-traumatic stress and bills for treatment and lawyers. It also turned her into an advocate for victims.

Following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, the former Air Canada flight attendant co-founded the Canadian Coalition Against Terror, and convinced MPs to pass legislation allowing victims to sue state sponsors of terrorism such as Iran.

She testified before parliamentary committees, fought for a federal ombudsman for crime victims, and had Sept. 11 declared the National Day of Service in Canada.

More recently, on Aug. 20 she represented terrorism victims on a United Nations panel marking International Day of Remembrance of and Tribute to Victims of Terrorism.

“I have some victories,” she said.

But there is also unfinished business. The accused 9/11 mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, was caught in Pakistan in 2003 but remains on trial.

And there have been setbacks, most recently the return to power of the Taliban militants who harbored Al-Qaida’s leaders and network of terrorist training camps.

“There hasn’t been any justice for me,” Basnicki told Global News in an interview.

“There probably never will be.”

Still, she feels she can help make things better for victims, building on the experiences she endured.

Maureen was at the Hilton Hotel in Mainz, Germany, on an Air Canada crew layover, when she turned on CNN and watched hijacked planes ramming the World Trade Centre.

She tried to call her husband Ken, who was at a meeting on the 106th floor of the North Tower. He didn’t answer.

But he managed to relay a message through his mother, telling her the room was full of smoke, the roof was blocked and he didn’t know how he was going to escape.

And then the line went dead.

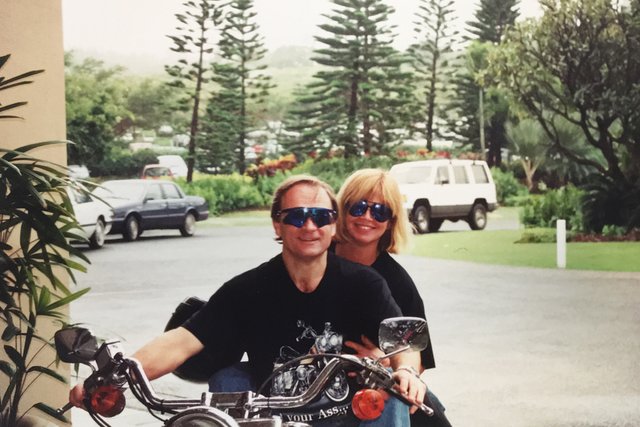

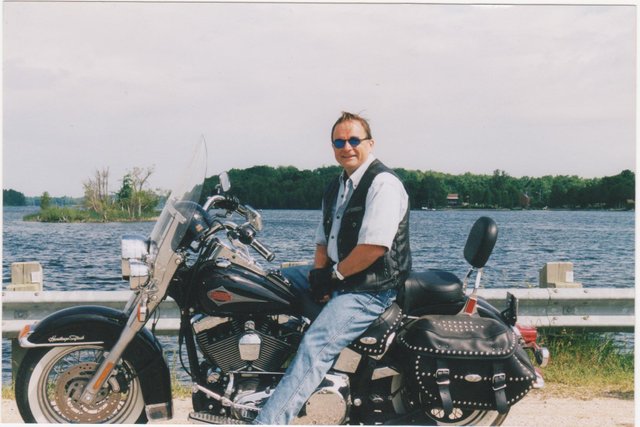

Ken was fit and calm under pressure. He rode motorcycles, coached his kids’ teams and had been building a home in Collingwood, Ont. If anyone could get out of a burning building, it was Ken. But as the days passed without any word from him, they knew he hadn’t made it.

Heartbroken and in a fog, Maureen found herself largely abandoned. She had her friends and family, but no official assistance, she said.

“No federal help, only photo ops,” she said.

She could have used it. There were forms to fill out, papers to sign. Insurance companies and lawyers. She had to figure it out by herself, but she angry and frustrated, and it was hard.

“I just wanted to cocoon and try to heal,” she said.

It wasn’t until April 2002 that the Ontario Office for Victims of Crime tracked down her daughter, Erica, and asked if she needed help.

Unable to bring herself to return to work on planes, given how her husband died, Maureen was referred to the Canadian Red Cross for financial assistance, but they wanted to see her grocery receipts for the six months before the attacks.

“Who saves grocery receipts? Certainly, I didn’t,” she said.

She did eventually receive aide, “but do I think that I got the proper compensation from Canadian Red Cross? I just will never know.” That’s because the man who handled her case fled to Africa after learning he was wanted for fraud, she said.

A year after the terrorist attack, the first of three shipments of Ken’s body parts arrived from the United States. A comb he’d left in his car at the airport provided the DNA match.

But his death certificate said that his body had not been found. Now that the search had turned up remains, it was deemed invalid, so she had to start again.

“It was just overwhelming,” she said.

Days later, a letter arrived for Ken. It was from the federal government. She opened it and learned that, rather than offering help, the government wanted her to pay taxes on her late husband’s income.

In the U.S., 9/11 victims were given a pass on income taxes for the years 2000 and 2001, a gesture of support. But Canada would not do so.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” she said.

In speeches and testimony, Basnicki has called for a national strategy to support victims of terrorism and mass violence, whom she said need proper compensation, treatment and justice.

“There is no plan or policy in place, not that addresses adequately the supports that are so necessary for victims of terrorism, for victims of mass murder,” she said.

Although terrorism is a federal responsibility, with minor exceptions, support for victims of crime comes from the provinces.

“This goes beyond the capability of the provinces,” Basnicki said. “The feds must step in and take care of their citizens.”

She said that while the federal government funds de-radicalization programs for extremists, and settles lawsuits, it has turned its back on terrorism’s victims.

“Victims’ rights and victims’ needs shouldn’t be pushed aside,” she said.

In 2013, Basnicki flew to Guantanamo Bay to watch the trial of several al-Qaida members linked to 9/11. She wanted to look them in the eye, and she wanted to meet other families.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed kept his head down throughout the proceedings, but Basnicki managed to catch the eye of one conspirator, Ramzi Binalshibh.

She stared him down, she said, and it felt like a small triumph.

Since then, Basnicki has convinced the federal Justice Department to help pay some of the travel costs associated with her role as a 9/11 victim.

After 20 years, she still misses Ken, but she’s found her advocacy has helped.

“I can’t change the past, I can’t bring Ken back,” she said.

“Really, the best legacy I can leave for Ken is doing what I’m doing in trying to help others and make changes.”