He was fast asleep, and I had been staring at him for the past 40 minutes or such. From the outside, I’m sure it looked like some sort of dad and newborn son bonding moment. First trip parents have this habit of looking as mesmerized as their infants.

But the truth is, I was not really looking at him anymore. My vision was unfocused, my attention inwards. Three days after my firstborn first came to this strange world, I gave myself an unsolvable puzzle: “What do I need to teach this creature?”

This question brought things into perspective in an unsettling way. I knew how to order pizza, how to pay taxes or how to drive a car. Above all, living in the São Paulo megalopolis, I had been honed and shaped as a master of work. Yet, none of this seemed fundamental, intrinsic to life. What was it then?

So I wondered while I wandered through the LED-lit city streets.

A concrete breath

Life is pretty sweet for an art director in “Brazil’s New York” — or so I would think while eating smoked salmon sushi paired with Belgian draft beer. People think Paris or Sydney are big cities, but only if they’ve never experienced anything like my hometown. Even the original New York is dwarfed by our 12 million inhabitants (and counting). Anything any other big city has to offer, we have it with extra bacon on top.

Perhaps the most important thing a big city offers you is access to knowledge, particularly access to knowledgeable people. No matter how specific your area of interest is: perhaps you’re a big fan of baking reality shows — well, there’s a real chance that a specialist will visit your city one day or another.

So I looked far and wide for the people who seemed to carry a piece of my new jigsaw — what are the fundamentals of a good life. This is how I ended up finding Joanna Macy, an amazing American environmental activist and scholar of Buddhism, and signed up for a four day retreat.

It changed me.

I started to move away from finding the answers to the important questions and instead I was searching for the systems that operate around those questions — I felt my questionings were somehow fresher. If we need food to live, then where does it come from, what does it do inside my body and where does it go? I got interested in permaculture, bioconstruction, and systems thinking, and I spent all my free hours trying to learn how to apply them myself.

It was by no means a quick process: years went by, we had another baby boy, and still the ball was spinning around the ring, taking its sweet time to land. Yet, the path led to an inevitable (and weirdly enticing) conclusion — our just-like-our-parents’ São Paulo life was not helping us teach the truly important things to our children.

A few months after yet another permaculture immersion retreat, my wife (nicknamed the Wizard, long story) and I finally amassed enough courage to play our big poker move: we sold everything. Our apartment, our TV, our chairs, our damn door knobs — all to fuel a dream of buying a piece of land in the green and fresh outskirts of our town.

We have a common expression in Portuguese: “When I got here, everything was bushes” — something similar to the English expression, “before it was cool.” Well, in our case it was very literal. Our beloved new home was nothing but a bunch of grass and more bushes than you would believe. In fact, it was so wild that it was pre-Stone Age uninhabitable, so we rented a small house in the nearby town. A provisory arrangement so we could start preparing our new home.

While I spent a big chunk of my time trying to raise money for our daily life and to afford the many specialized services a new house needs, the Wizard was juggling between taking care of our little boys, finding where to obtain unusual building materials, and teaching yoga. Luckily the Wizard can always count on her enchantments.

So, the real journey has begun… from dream to drawing, from drawing to building.

With our bare hands.

We’re not in Kansas anymore

Fine, we did use our bare hands a lot, but admittedly not everything was manual labour — and that was a problem.

Two city-dwelling souls living in a tiny nowhere village was challenge enough: if you needed something, it will not always be available. That might sound pretty normal to many of you, but to me it was extraterrestrial. What do you mean when you say that no store in town have spare drill parts?

What do you mean when you say no store in town ever had any spare drill parts...ever?

It’s amazing how many things I took for granted — I remember after our second month there I’d have sold my soul for a simple washing machine. Phone signal became a luxury, electricity was not always guaranteed, internet was bumpy (and honestly it still is). I remember, years later passing by São Paulo, just looking at the asphalt on the street and thinking, “thank you for being here,” and also imagining all the many invisible labours that putting that blessed thing there represented.

Some days the countryside gods were so displeased with us that we’d drive somewhere and by the time we were going home, the dirt road had been destroyed by a tropical storm.

When that happened, we’d sleep on somebody’s floor. I cannot thank them enough for their kindness, but still I felt the whole deal was a bit humiliating. Why did I leave my wonderful apartment and my food delivery app to put my kids to sleep in someone’s couch?

During moments like this I’d look at my children expecting to be chastised — I guess the Wizard and I were always too attuned to the financial and infrastructure crisis happening almost daily, and we expected our little ones to be just as well.

Instead, I’d find them sleeping. To them, sleeping on somebody’s couch was just part of life — they adapted much quicker than we did. Looking at them, I’d relax my shoulders and my worries. It felt like living inside one of those Pixar movies where the children understand some layers and adults understand others. Somehow, it was working: this whole great escape was already teaching them many of the truly important lessons.

The problem laid with the grownups.

I was juggling all my tasks the best I could so I could still keep my old art director job remotely. It was tricky and headache-inducing sometimes, but doable. The Wizard had a tougher time: she used to teach yoga for big companies and made a good buck out of that — in fact she earned significantly more money than I did. Now, all of the sudden, she was earning very close to zero. For the first time since she moved away from her parent’s place, she was a financial dependant again.

You might think you’re ready for that, you might plan it step by step in your head, but you’re not. You’ll never be. Perhaps if you anticipated how difficult it would be, your courage would fail you.

Some days were just fine, others she would wander around the house feeling lonely, even when the kids were around. Fights would break out between us and again and again I had that feeling of what the hell am I doing here. I remember wondering if we could persist on being together.

Eventually she found a job as a physical education teacher at a local school — it was stiff work: the education methodologies were quite archaic and the money was a mere shadow of her former São Paulo wages. Yet, it was a beginning — above all it was the perfect excuse to connect us with the local community.

It was the beginning of some sort of emotional spring — and the rewards would soon follow.

Distinguished members of the audience

Picture that: a pleasantly warm evening in the middle of a wild place, around us a cacophony of chirps. We’re all preparing to go to sleep while the fireflies make beautiful patterns everywhere — we need to mind them because tonight my family and I are sleeping inside a camping tent.

Surrounding us, the unfinished walls of our half-baked new home. There’s more bricks laid down today than there were yesterday. We’re all smiling, chatting about windows and kitchen sizes: our new place is so customizable that it feels like playing some sort of colossal Lego game.

It’s amazing how freedom can paralyze you sometimes. The beginning of the construction was a bit delayed, exactly because we could do anything! How big do you make your home when the only limitations are your imagination and vigor? How do you organise the rooms? Do we really need rooms? Why?

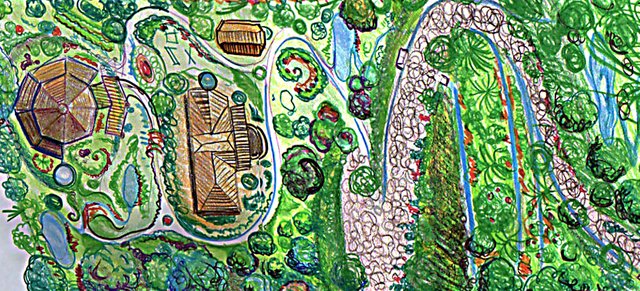

It all came together one day when I was doodling possible homes. My first 14 drawings looked like versions of the same old blueprint with various sizes of living rooms and toilets. As an artist, I knew this was going nowhere, so I started with something different: a circle. It clicked. Perspective and context were always big drivers. The geographic and climate conditions worked as constraints to guide bold decisions. East, West. North, South. The strong winds directions, the sun movements from solstice to equinox. I felt alive and I felt the paper could feel it.

3 months later, our new house looked like a big circus tent, an illusion boosted by our quasi-lack of internal walls, the different spaces separated only by colourful pieces of fabric. I gotta say, it really looks like a great place to play: so my children played. They ran around and climbed on the windows they built themselves — even a round window by their own suggestion! Why not? We could do anything.

The locals, who really went out of their way to help us stack the bricks and install the electric system, were delighted. From the start our new place was a powerful gathering spot: with didgeridoo classes, ecology workshops and potlucks happening weekly. We hosted people from all around the world and even (to my utter delight) some permaculture jedi masters.

It was a dream.

Except when it was not.

I saw the guys in the distance

It was not the first time it happened, but soon enough I’d find out this instance would be different. While I prepared myself, armouring my body with the thickest of all my clothes even under the scorching Brazilian Sun, the guys vanished. It meant it was about to begin.

The fire started gingerly, as they always do — an orange glow colouring the forest’s green. The dry day helped: quickly the blazes were roaring. For the longest time I felt so angry that I refused to believe there was a reason for someone to set a forested area on fire, I’d rather think the people who did this were just evil. Turns out, of course, that there’s a profit to be made, a whole fire market.

It was time for my last preparation: a cold bucket wash. It served to contain the heat, but also to heighten my senses.

It always felt to me that the worst part of dealing with the wildfires was that I was forced to destroy what I had so dearly created: a huge chunk of the firefighting work was to keep the flames away from fuel, that meant hastily removing small trees and bushes from its possible path.

I knew the fire was stronger than I was, so I’d sacrifice a part of my own reforestation area as a tribute to this angry entity — and I’d do my best to create some sort of wet barrier where the fire could not spread any further.

I was lucky the first two times. This time, when I got closer to the action — my whole body sweating profusely — I thought that was it. It was too big. I’d have to run back home, save a couple of precious belongings and flee. The fire was spreading so violently that I’d even miss the chance to see my dream house burning to the ground.

Somehow I persevered — I don’t think my brain was functioning in its perfect state that day. While I desperately fought the flames (and even fought for my own safety a dozen times), I kept thinking it was all for naught. It was too big, too quick, too destructive. Why would these people set fire to this beautiful place? To my family? Too big. Quick. Destructive.

By the end of the day, I had lost a lot — but the house was still standing. My muscles aching, I thought to myself that it would take over a year to rebuild and plant everything we lost, and who knows when I’ll see the guys in the distance again? I didn’t cry that day after the fire, but I had a somber expression.

The Wizard approached me in my gloomy mood. She waited until I was ready to talk, which was a while. I asked her exactly what I was asking myself: why did I bother? Why did I risk my life putting out a fire if other fires were to come?

That day she told me something I’ll never forget. She said:

— “You didn’t go out to put out a fire today. You went out to show your children how to find the strength to fight for what you care about.”

What comes after home

But the next fire hasn’t come, and everything was rebuilt and even expanded. If the fire comes again, we’ll deal with it — this time with more experience and more tools. If anything comes, we’ll deal with it.

While I was writing this tale, I looked up and there was my son — the same son I saw in a cradle a lifetime ago, just a bit bigger now.

I realised I knew everything about him.

The ideas that influenced our family to go through this journey were so powerful that they seeped into other areas. Our relationships have reinforced beams we installed ourselves, our conversations are cyclical and its byproducts are used in songs. We live in our circus tent and we really know every detail in it — and in ourselves. Even more: by creating this environment, we’d somehow created a powerful invitation, a social magnet. Our house is always full of movement, of knowledge, of people who want to be here.

It felt to us that we had somehow surpassed the rank of home — we needed a new word to represent our attunement state. Thus we came across Waru: a term originally from Australian aboriginal people that means, “a way of living that improves others’ lives.” It might sound poetic, but to me Waru has a very bioconstruction-inspired realness to it, as if the word itself felt like the clay I could build a house with.

I remember one day overhearing my sons’ conversation — they decided they’d raise chickens. Among them, ages 10 and 13 by then, they chose a place and a size for the coop, and they made sure to dedicate some extra energy so the chickens wouldn’t feel cold during the chilly days. When the plan was laid down, then they came to me to ask for advice and materials. I was suddenly the sidekick and couldn’t be prouder.

Finally, I had an answer to the difficult questions I asked myself right at the beginning: what is really fundamental to life? What should I teach my children to improve their existence?

Better yet, I didn’t have an answer: I had a process. Whatever I was thinking I should teach my newborn son all those years ago proved to be a two-way street. I learned as much as I taught. Every new idea had a ripple effect.

This is not a lesson you can get from a book: you need to live it every day. Our captured rainwater becomes our next soup. Our waste provides the nutrients that our banana trees need. Our conversations transmute into invitations to the community and eventually gatherings, classes, encyclopedias.

Every system is thought through — from electric insulation to emotional triggers. We’re in constant contact. We depend on each other and we wouldn’t want it any other way.

Yes, that is my home. But it’s also more. It’s Waru.

This story is part of a new series called Enspiral Story Dojo, a place of tales about practice and transformation into a life with more meaningful work.

This tale was about (and co-written by) Renato Inácio, a designer and permaculture enthusiast living in the countryside of São Paulo, Brazil. Narrative support by Joriam Philipe, Enspiral catalyst.

If you’re curious about Enspiral and its participants, you can read more here or support the network.

Congratulations @enspiral! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPVote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit