The Role of Law is to Embody and Enforce Morality

The following paper will explore the idea of law enforcing morality and law embodying morality. The latter concept is argued against by positivist jurists, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Austin, but supported by Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword. Enforcement of morality by use of law is supported by Lord Patrick Devlin and opposed by H. L. A. Hart. Both, Jeremy Bentham and John Austin are jurists of positivist inclination and are arguing that positive or man made law is no way dependent on morality. Some positivists adopt an approach developed by Kant where laws are regarded as external influences on human conduct and morals govern internal conduct. On the other hand, Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword build their argument on the notion that law is a moral phenomenon, hence according to them there is an intrinsic connection between law and morality. Lord Devlin argues that morality, acts as cement to human society, has to be protected through the use of law, especially criminal law. H. L. A. Hart on the other hand, opposed Lord Devlin’s views on the basis of lack of evidence and other factors which will be discussed later in this paper. However, an optimal view, is that law needs to be morally sound but in no way should law enforce morality.

What is Natural Law and Legal Positivism?

Natural law and Legal Positivism have opposing views on law and morality. However, both theories overlap in a sense that they both advocate that law affects our reasons for action from within. Natural law advocates believe that valid legal rules create moral obligations and those advocating Positivism view laws in a morally neutral way. Natural law theorists see law as a reason for action and therefore argue that law cannot be understood without morality. Legal Positivism theorists see law as a social institution therefore making a morally neutral approach possible and valuable.

Law embodying morality

Classical Natural Law theorists claim that man made laws are not valid unless they pass through a moral filter. They argue that every law has to have some moral value to it. There has however, been a major change in Natural Law theory, many Natural Law jurists oppose the idea of a moral filter due to its’ incompatibility with the real world application. Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword argue that law is a moral phenomenon, that law stems from community morals. They contend that law is founded directly upon morality. In Law as a Moral Judgement the authors blatantly state that ‘the thesis that the concept of law is morally neutral … is wrong’. Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword argue that rules exist solely to deal with social problems, existence of such rules can only be explained in ‘reference to conditions of human social order, which presupposes a moral base to the order which is thus to be maintained.’ Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword theorise that any rational person that performs an act, has done so by reference to a supreme moral principle.

They also support a view that a duty to obey laws relates directly to the moral quality of those. As was stated in Law as a Moral Judgment ‘Laws, for us, are morally legitimate prescriptions … and they straightforwardly generate legal-moral obligations.’ Therefore, laws which are both moral and formally identified must be obliged with. However, Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword do agree that formal identification and morality of law are not absolute prerequisite for obedience of law. Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword knowledge that there are instances where one element, or the other, is not fully present. They also agree that it does not mean that the laws in question are null and void, some degree of obligation still stands to preserve an overall morally robust system.

Such thesis is congruent with the Natural Law theorists. One of them John Finnis, in his work Natural Law and Natural Rights, discusses a multifactorial influence on obligation to follow laws. Finnis' notion of ‘collateral moral obligation’ is in sync with, what was later proposed by, Deryck Beyleveld and Roger Brownsword in Law as a Moral Judgment known as ‘external synthetic collateral obligation’. Both concepts support the idea ‘that in disobeying a law, a person places at risk the whole legal system and that there may therefore be a ‘collateral’ moral obligation to obey such a law’.

One of the biggest advantages of incorporating morals into law is that morality can act as a stopping mechanism to ensure that laws are not abusive of individuals’ or groups’ rights. For example, before and during World War II a positivist approach to laws was the dominant one. This resulted in a large scale legal abuse in Germany, because of positivist approach focusing on the descriptive aspect of law and not it’s moral validity. The disadvantage of such approach is that there is no objective standard of minimum moral validity of law. It can be argued that individuals create their own moral threshold.

The opposing view to the Natural Law theory of law embodying morality is the Legal Positivism supported by Jeremy Bentham and John Austin. These theorists claim that law is a set of standards governing human behaviour and those standards are in no way connected to morality, and the existence of those norms is only granted by the threat of sanction. Jeremy Bentham and John Austin do not deny that morality can play a part in law, but it is in no way essential.

Jeremy Bentham does not accept the notion of natural rights, he judges law by its efficiency. Jeremy Bentham regarded legal morality as ‘lying in the greatest good of the greatest number’. He argued that it is much more efficient to lay down strict codes and rules, as it will allow ease of governing without hinderance by chaotic moral tests. Jeremy Bentham, along with John Austin, believed in the ‘separation thesis’ which states that existence of law is one thing and its merit or demerit is another. Essentially arguing that there is nothing that connects law and morals, however there are instances where laws can have a moral tone, due to influences of people’s pre-existing morals. It is important to understand that there is nothing that dictates that law is intrinsically infused with morality.

John Austin very much supports the idea that law’s validity comes entirely from its source in an act of a sovereign. Because law is positive in nature (man made law) it can have any kind of content, regardless whether it is morally good or morally bad. John Austin explicitly separates positive law from its merits and demerits and does not deny that sometimes positive law conforms and sometimes conflicts with divine law.

John Austin acknowledges that empirical scientific approach alone cannot sufficiently explain the necessity of certain legal norms. He argues that ‘certain kinds of legal institutions are necessary because of the moral requirements of human life and other human goods’. This deduction allows to assume that ‘merely contingent norms of human law demands a science of jurisprudence both empirical and moral’. John Austin’s study of Gaius has led him to uncover that ‘every independent nation has a positive law and morality (‘leges et mores’), which are peculiar to it-self . . . . Every nation, moreover, has a positive law and morality which it shares with every other nation’. However, John Austin does not fully support such claim, he calls it speculative rather than practical.

John Austin being a utilitarian philosopher, denies that there are acts which are seen to be intrinsically evil due to lack of moral standing of such acts, and other acts are seen as evil because they are prohibited by state. John Austin acknowledges only one reasoning that tests moral principles, that is their empirical consequences.

One can say that human law contains both elements of the above theories. However, positive law, in isolation, enables political powers to trigger an immense coercive power of the state. Such process can lead to tremendous disturbances, such as seen during World War II. Positive law tends to create new obligations for those who in no way consent to them. Therefore a moral filter may serve as a safety mechanism to avoid drastic consequences.

Law enforcing morality

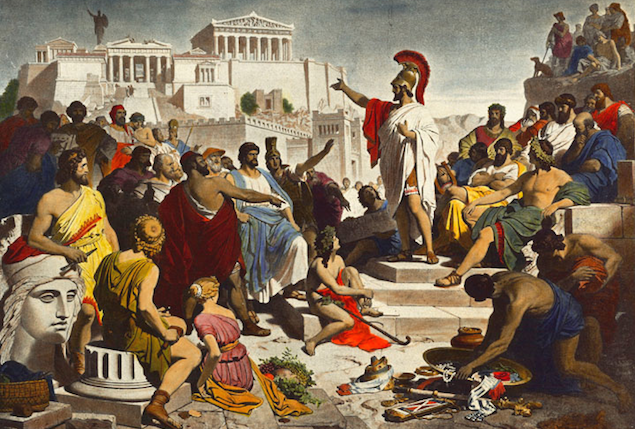

Plato held a view that law does not simply exist to ensure that people lead a morally good life, it is there to enforce such a lifestyle. This notion assumes that law will be used not just to enforce morality but also to punish those who do not conform. In the 1960s a heated debate erupted between H. L. A. Hart and Lord Patrick Devlin and it ended with Lord Devlin losing that debate.

Lord Devlin strongly argued that public morality holds society together and that criminal law is there to uphold such public morality. Public morality is decided on what the public feels, therefore specific legal punishment would also depend on what the public feels like. In accordance with that principle it is safe to assume that if public feels outraged by homosexuality it is ought to be sanctioned. Lord Devlin believes that when society’s morality is challenged and is not sanctioned legally, it puts the integrity of society in danger. Such thesis, to some extent, was upheld in a court room where R v Brown was decided. The notion of morality holding society together is termed as ‘disintegration thesis’.

According to Lord Devlin every society has a right to uphold its’ own values and protect own existence. If that is the case, then law should be used as an instrument of societal protection. Lord Devlin does, however acknowledge that there are limits to this thesis. Most importantly he outlines that the biggest safeguard is the principle that there needs to be a balance of individual freedom that is consistent with integrity of society. At the same time Lord Devlin omits to point out his previous claim, that when public feelings of disgust and condemnation run high, legal sanction must follow, and if the feelings do run high how would a society know that the danger is great enough to warrant such sanction?

H. L. A. Hart opposes Lord Devlin’s view with some compelling arguments. First and foremost, H. L. A. Hart points out that ‘disintegration thesis’ is a central point to Lord Devlin’s argument, he then proceeds to give examples of how Lord Devlin describes such thesis. ‘Moral structure’, ‘public morality’, ‘a common morality’ are some of the examples H. L. A. Hart provides. He then states ‘The disintegration thesis, under pressure of the request for empirical evidence to substantiate the claim that the maintenance of morality is in fact necessary for the existence of society, often collapses into another thesis’. This other thesis is the ‘constructive thesis,’ meaning that society ought to enforce moral convictions as it has a right to follow own moral views, and that the moral environment is something that has to be protected from change.

H. L. A. Hart acknowledges Lord Devlin’s position but also points out that there is no empirical proof for Lord Devlin’s claims. Lord Devlin refers to historical trends of societies’ loosening moral bonds as a first stage of disintegration, but gives no supporting evidence to such statement. Even if he attempted to provide evidence, one would look at disintegrated societies of the past and try to ascertain a causal link between change in morality and societal collapse. Although, ‘would such evidence be persuasive in considering modern societies?’ H. L. A. Hart goes on further so say that a mixture of different morals, seen in contemporary Britain, supports the notion that different moral stances lead to co-existence and tolerance, rather than disintegration.

In short, Lord Devlin strongly supported the argument that law is ought to be used as an enforcing instrument of morality by the state. Lord Devlin saw moral deviance of the same category as state treason and thought that the state had every right to protect the society from such danger. Lord Devlin strongly supported the notion of society having a right to make a judgment in accordance with contemporary morals, he argued that such judgment was essential for survival of the society.

H. L. A. Hart has acknowledged the need for law to enforce some morality, but he denied such application in a contemporary society. It appears that H. L. A. Hart agrees with Lord Devlin on the notion of minimal shared morality for a society to survive. However, where does one draw the line of how far the state goes to enforce morality? John Stuart Mill established the ‘harm to others’ principle and H. L. A. Hart upheld it. Furthermore, H. L. A. Hart added an element of paternalism to the ‘harm to others’ principle but unfortunately he never defined the meaning of paternalism. Although it is speculated that the notion of paternalism may refer to the prevention of self-inflicted harm. ‘Harm to others’ with paternalism aims at minimising self-inflicted harm to those who lack intellectual capacity and are in some way infirm.

In conclusion, law should be embodying morality, it appears that Natural Law jurists make a stronger argument that those of Positive and Utilitarian persuasion. The moral safeguard which dominates Natural Law is an appealing concept, especially after the events of World War II. Hopefully in contemporary society legislators would ask themselves whether the bill they are debating contains some degree of morality and is not completely repugnant to societal moral conscience. As for enforcement of morality H. L. A. Hart makes a much stronger argument. Law is ought to stay out of citizens’ private affairs, otherwise core values such as democracy may be threatened, simply due to the state deciding it is not ‘morally fashionable’ any longer.

Bibliography

A Articles/Books

Beyleveld Deryck, Roger Brownsword, Law as a Moral Judgment (Sweet & Maxwell, 1986)

Bix Brian H., Jurisprudence: theory and context (Sweet & Maxwell, 6th ed, 2012)

Cosgrove Richard A., Scholars of the Law (NYU press, 1996)

Dworkin Ronald, ‘Devlin and the Enforcement of Morals’ (1966) 75(6) The Yale Law Journal

Finnis J. M., Natural Law and Natural Rights (Clarendon Press, 1980)

Freeman M.D.A, Lloyd’s Introduction to Jurisprudence (Thomson Reuters, 8th ed, 2008)

Hart H. L. A., ‘Social Solidarity and the Enforcement of Morality’ (1967) 35(1) The University of Chicago Law Review

Marmor Andrei, Sarah Alexander, The Nature of Law (7 August 2015) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lawphil-nature/#Aca

Martin Daniel, ‘Legal Positivism: Hart, Bentham and Kelsen’ (2014) 1(2) The Carrington Rand Journal of Social Sciences

Moens Gabriel A, The German Borderguard Cases: Natural Law and the Duty to Disobey Immoral Laws (Butterworths, 1996)

Murphy James Bernard, The Philosophy of Positive Law (Yale University Press, 2005)

Penner J. E., McCoubrey & White’s Textbook on Jurisprudence (Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 2008)

B Cases

R v Brown [1994] 1 AC 212

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit