Victor Hugo, in one of his best-known and at the same time most exciting works, highlighted some of the numerous secrets that affect one of the most spectacular cultural beacons of the medieval heritage of the West: the Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris.

The work I am referring to, entitled, precisely, Our Lady of Paris, depicted the presence, in those dizzying heights dominated by grotesque gargoyles, of a character, apparently terrifying, but paradoxically tender, whose myth still continues to enchant the imagination of our children: Quasimodo.

Naturally, keeping all the distances, something similar could be placed in the heights of one of the most fascinating cathedrals in Spain: the Cathedral of Saint Mary of Burgos.

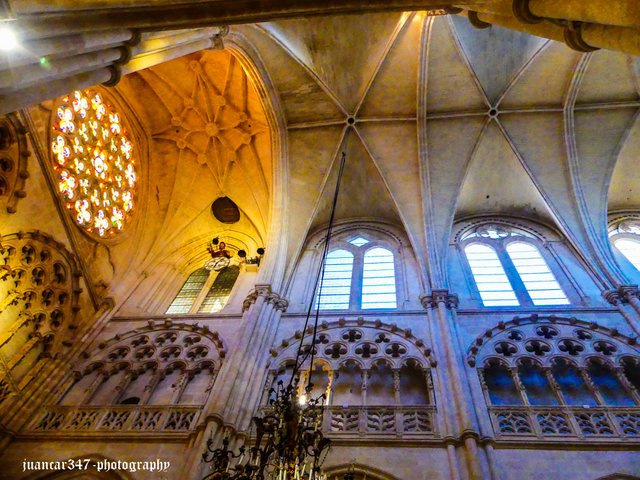

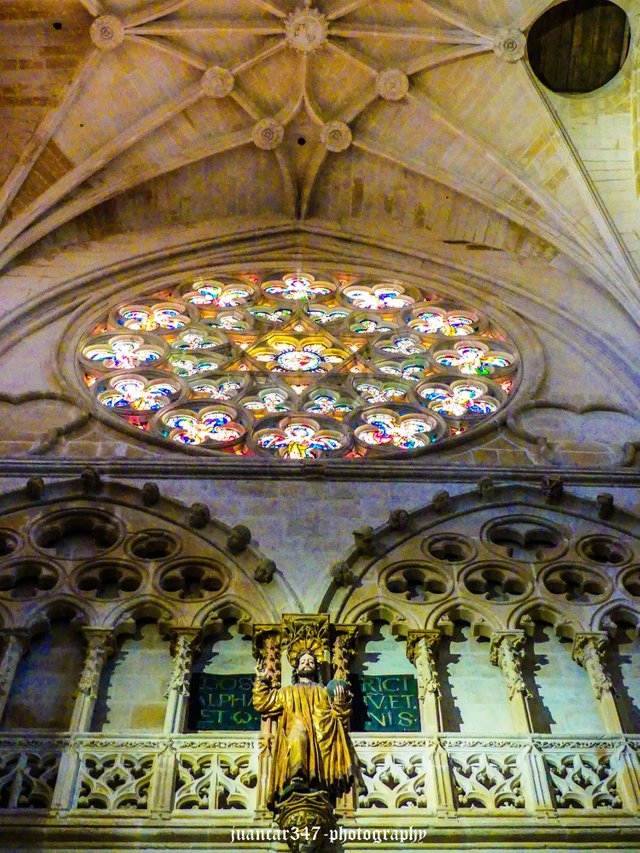

Begun in 1221, within the walls of some walls, which, today, barely preserve several of the formidable doors that protected it in those turbulent times of reconquest and siege, of advances and retreats, the Cathedral of Saint Mary is not only a metaphorical textbook that gathers, in its fascinating pages of stone, a good part of the knowledge, both architectural and artistic, of a style, which, emerging as a natural evolution from the obsolescence of previous styles, such as the Romanesque, according to some historians, still exerts a seductive influence on the spectator, due to the influence of its elegance and fantasy: the Gothic.

Leaving aside the fact that not only masterful architects but also important sculptors and designers participated in its construction, who, throughout the different periods, left precious details of their skill, the Burgos Cathedral is also, by default, the repository of countless beauties, which, distributed throughout its spectacular layout, powerfully attract attention, challenging the imagination of the visitor with their cryptic messages.

But legends and traditions are, in addition, an essential part of its most ancient secrets and offer the opportunity to verify that, after all, even in those times, dark for some, there was a glimmer of a dream with a mechanics, which, in some way, anticipated robotics.

This is where we can place the comparative Quasimodo of the Burgos Cathedral: an automaton, which, located on the main façade, the façade of Saint Mary, in the frame of a pointed window close to the triforium, opens its mouth and rings the bell every hour on the hour.

Its appearance, also somewhat grotesque, like Victor Hugo's Quasimodo, draws attention, perhaps because its ironic smile, together with its goatee and also the inflexible scrupulousness it has when ringing the bell, opening and closing its mouth, can become like a diabolical warning that, sooner or later, time catches up with us all, calling us by our name.

And as the poet John Donne said: ask not for whom the bell tolls. It tolls always for thee.

NOTICE: Both the text and the accompanying photographs are my exclusive intellectual property and therefore are subject to my Copyright.