A core function of skepticism is the analysis of concepts. It works alongside traditional scientific skepticism, which investigates claims in a direct, hands-on way. One advantage that analysis has over investigation is that it can be done purely in the mind, and thus avoids limits on travel, time, or investment of physical resources.

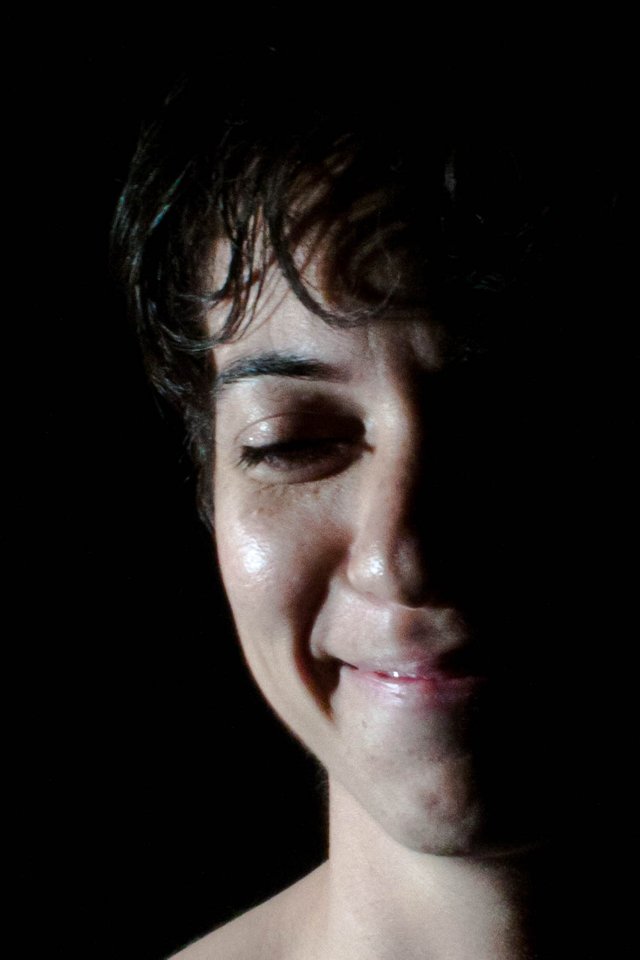

Consider the notion that taking a photograph of a person “steals his or her soul.” For most of us in developed countries, this idea seems like a pre-technological fear born of simple ignorance of photography. It’s an easy concept to dismiss, as it seems so simplistic and overtly fallacious. But I claim there is value in actually considering this notion more carefully, because it functions to exercise our critical thinking skills, and it demonstrates that there is often a great deal going on with an extraordinary claim if we simply think about it carefully.

First off, I’m going to take the claim at face value and assume that it’s not been articulated in a precise way by a theologian. At the very least, it can be differentiated from beliefs about photography by groups such as the Amish. For them, photographs of members of the community may be considered “graven images” and as such violate the Bible’s second commandment. For some Amish, the issue of consent becomes a factor, as active participation in their own photography is considered prideful, and thus sinful.1

The religious and spiritual beliefs of some cultures are not detailed in written records. Anthropologist and photography librarian Carolyn J. Marr2 notes that some Native Americans stated they did not want to be photographed based on the belief the photograph would steal their souls. Nevertheless, this was not a belief held by all Native Americans, as many examples of carefully staged and posed Native American portraits exist.3 The ill-defined nature of the fear of soul theft even makes an appearance in pop culture humor. In the Futurama episode “The Thief of Baghead,” the characters debate whether their souls or their “life force” was sucked out of their bodies by a photographic print.4 Even as a comedic device, the Futurama segment illustrates the very concept of the “soul” is fuzzy, to say nothing of its empirical foundations.

Assuming that some people at some times have genuinely believed that photography can steal their souls, how do we begin to analyze this claim? It’s safe to assume that the soul is made of light, for why else would there be a concern that a machine that captures light is capturing the soul? If the soul were something besides light, then we might worry it could be captured by a vacuum cleaner, a fishing line, or a Ziploc bag.

During the act of soul theft, we must ask when this occurs, as the process of photography is not instantaneous and neither is the movement of light. Does it happen when the shutter first opens or before, when the light first enters the lens? Maybe it happens when the light hits the negative or the electronic sensor. Perhaps it waits until the image is actually printed, or maybe electronically shared.

Consider that light can be captured without lenses, such as with a pinhole camera. By thought alone, we can eliminate the lens as a necessary condition of soul theft. Is the negative or sensor a necessary condition? What about the use of a camera obscura? What if the person’s light is not captured automatically, either chemically or electronically, but rather applied by a human hand? An artist can certainly draw or paint a very realistic image of a person onto paper or canvas using a camera obscura or camera lucida.5

Is the soul one thing, or is it divisible? If each human has only one soul, then what happens if I take two photographs of a person? Is their soul stolen twice? If the soul is one thing, like the Statue of Liberty, can it be in two places at one time? If it’s argued that the soul is incorporeal, and thus could be omnipresent, then why are we worried about cameras at all? If we accept that the soul is light and can be stolen by cameras, then what about black and white photographs? Do color photos have more soul than the souls Diane Arbus might have stolen? There seems to be a tacit assumption in all this that we’re talking about visible light. Yet humans most certainly give off invisible light in the form of infrared (IR) radiation. If I point an infrared thermometer at you, I gather your infrared light. Do I still steal your soul? The IR thermometer forces us to consider whether our souls exist only in range of frequencies visible to other humans. The metaphor of the IR thermometer offers another conundrum as well, as many consumer-grade IR thermometers simply give a digital numeric readout of the temperature of whatever is being measured. In this case, the result can be thought of as the “brightness” of one color of whatever it is that is being measured. Essentially, it’s the numeric readout representing a single color. In conventional photography this is known as a histogram, which is a chart representing the multiple color values of a photograph. This raises yet another issue: Assuming for the sake of argument that a soul is captured on a digital sensor, what then if we are only provided a numeric or graphic readout of its electronic values? Odd as it may seem, this is essentially what’s happening when we point an IR thermometer at a surface. If we concede that we are not stealing a soul simply by remotely measuring a person’s temperature, why is this so? Is it because seeing a non-abstract, non-numeric representation of the person is a necessary condition?

There is also the tacit assumption that our souls are only the light reflecting off our skin, which is an organ that only makes up a fraction of our bodies. Consider an endoscopy. Can a gastroenterologist accidentally steal your soul if he snaps a picture of your large intestine? Your colon is no less a part of you than your skin.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that a necessary condition for soul theft is capturing the light that comes off a person’s skin. With this stipulation, we completely eliminate images such as medical X-rays. But what about so-called “millimeter wave scanners” now commonly found in American airports? In this case, reasonably detailed images of a person’s skin can be seen beneath clothing. In such a case, would a person’s soul be stolen even if they were totally covered, as in a burka? Setting aside the esoteric technology of millimeter wave scanners, another question is raised. Consider that most people are wearing at least some clothing when photographed. Since most people’s visual identity is strongly associated with their faces, perhaps the face being visible is a necessary condition of soul theft. What if we wear a mask? From there it’s a bit of a slippery slope, as one could continue covering or hiding one’s self further and further until completely occluded. Is there a point along the continuum from being completely naked to being completely covered that soul theft could or could not occur?

As with matters of law, intention plays a huge role. For a theft to occur we need a thief. Perhaps the presence of the photographer is a necessary condition. But now we have another problem, as we need to account for self-portraits. Can a person steal their own soul with a selfie? Is it even a meaningful concept to steal something from yourself? All the other conditions we suppose might be necessary are there: a machine for capturing light, a photographer, a person being photographed, and a non-abstract representation of the person. But perhaps our thinking is too limited here; perhaps something entirely else besides theft happens. Perhaps the soul discorporates and leaves the body during the selfie, yet returns when the image is posted on Facebook.

Perhaps our thinking that the soul is “one thing” is too narrow. What happens when the camera is digital and the soul falls on the sensor? Is each pixel a mere part of the soul? In such a case we could consider that the soul might be holographic and that each pixel somehow contains the information needed to reassemble the whole soul.

Our thinking on this issue is also constrained in supposing there is only one camera functioning. What if we used two cameras to capture a stereoscopic image? This is not a fanciful concern, as stereoscopic photo pairs were quite the rage in Victorian times.6 A stereoscopic image is fundamentally different than any 2D image, as the 3D image is perceived in the brain of the viewer. But what does this mean for the soul? Perhaps the soul contains spatial information or more technically “Cartesian metadata” that was first perceived by Victorian thrill seekers.

What about distance from the camera to the subject? What if the subject is in the frame of the camera, but is too far away to be seen? If so, then souls were stolen en masse when the famous “Earthrise” photo of planet earth was taken during Apollo 8 in 1968. Is NASA the biggest soul thief of them all?

Troubling, too, is the subject of death. Are photos of deceased humans taboo too? Most conceptions of the soul describe it as leaving the body after death. Yet if a soul is light from a person’s skin, then there is still light reflected from his or her skin when he or she dies.

This exercise is intended to demonstrate that many extraordinary claims are poorly framed from the get-go. Even an assertion that sounds ridiculously simple on the surface can contain paradoxes, uncertainties, and multiple tacit assumptions. This is understandable in the study of fringe subjects, as many extraordinary claims exist outside the realm of conventional science, which places a huge emphasis on very precise definitions of concepts. The very subject matter of skepticism, analysis of extraordinary claims, offers the skeptic a fertile set of ideas that analysis alone may reveal as containing these paradoxes, uncertainties, and tacit assumptions. Before the hard leg work of scientific skepticism starts, time spent simply analyzing the initial claim is often very productive.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.csicop.org/sb/show/soul_theft_through_photography

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Dear friend! Next time also use #artzone and follow @artzone to get an upvote on your quality posts!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit