I've written one Pizzagate article before, which discusses my theories regarding the ancient origin of certain ruling class cults, and their relevance for American democracy.

I don't like writing about Pizzagate because I find it so upsetting, but as a friend lamented the lack of "professional" articles on the subject, I felt obligated to contribute a small piece.

Many men and women smarter than me have written about the central problem of interpretation: any interpretation, about anything.

Where do interpretations come from? There's a whole lot of answers to that one, but a good Enlightenment "scientific answer" is that interpretation of facts based on evidence tends to yield, at the very least, a reasonable simulacrum of the truth.

Let's leave the wikileaks emails out of our discussion of Podesta entirely. Regardless of what was meant by the "handkerchief containing a map that seems to be pizza-related," by and the large the more damning series of evidence of Podesta's guilt stems from his fascination with disturbing art.

Perhaps already we have to acquit him. This is no crime, of course. You can own any art you wish, presuming, I suppose, that it does not depict any illegal acts, but even then, it might be legal, even moral.

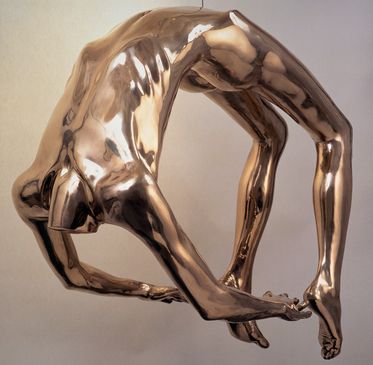

John Podesta owns a strange looking headless statue of a man that bears an odd resemblance to one of Jeffrey Dahmer's victims: the statue contorted in the same the body was discovered.

Again, let us say this is only evidence we have. We can't ask John ourselves; he doesn't answer questions like this. If we could ask his lawyer, I'm sure under duress he might only say something vague like "John categorically denies being involved in any illegal activity. These conspiracy theories are laughable."

We are confronted, in the case of this art, with what prosecutors most hate to present a jury with: a series of strange coincidences, from which they are encouraged to draw a conclusion.

Perhaps this article itself is entirely useless. Certainly I have found in so many discussions since the American elections in the summer of 2016 and all that surrounded that, with its competing hysterical narratives from both the mainstream and alternative press and from ordinary Americans of all stripes, that it's difficult to convince anyone of anything if they're not ready to move beyond their comfort zone.

Still, at least one of you reading this is ready to move beyond that comfort zone.

What, if anything, is a sensible conclusion to draw about someone who collects disturbing art?

As someone who produces disturbing art, I can say with authority that the process of producing it is cathartic, and healthy. Shrinks of all stripes advocate patients to write of their experiences, to help achieve "closure" and perspective on the traumas of your life. Even writers and artists who insist that their art, or even all art, must never be seen as a form of therapy, will admit that making art feels good, and helps the artist, and hopefully the audience, to understand one or two things about the difficult problems we confront in life.

None of that is controversial. And again, I myself own some disturbing art, in the form of the covers of my books, which depict strange fantastical creatures in dark settings. For me, my writing, and choosing to display the artwork associated with it, is a symbol of some public aspect of my psychological makeup: that I am interested in the dark side of human nature; that I believe it has something to teach us.

This could be true of John Podesta as well: as a politician, or "political operative" even the most innocent observer would agree that he is confronted (or participates in) some of the darker sides of human nature. His art, perhaps like mine, symbolizes his relationship with that dark side.

Still, John does not produce this art himself. So I think it is, at the very least, a slightly different relationship between man and art. For the artist, making disturbing art is usually therapeutic.

But even if you are not an artist, an obsession with "dark" art is not uncommon. Many normal, "well adjusted" people love horror movies, and human beings have loved ghost stories since time immemorial.

Someone who owned hundreds and hundreds of horror movies might be seen as a bit eccentric, but could just as easily be seen as a charming aficionado of a certain kind of art.

I do believe, however, that the problem of interpretation of man and art becomes necessarily more complicated when we are discussing powerful men and women.

I am a relatively unknown writer with a handful of readers and friends; and though as a "public intellectual," however modest, there is a limited sense in which my life is on display for the world, I am not under the same kind of scrutiny as a man like John Podesta who worked in a public capacity for the well known Hillary Clinton, trying to get her elected president.

It's one thing for me to own a statue that may resemble Jeffrey Dahmer's victim: it has no real public repercussions. My friends and family could see it, again, as a charming eccentricity or a disturbing fact about my tastes in art, but really it would end there.

If I were a political operative routinely inviting wealthy couples to my home to raise money for the Clintons and the DNC, such art takes on another quality: it is not solely about Podesta the man, but Podesta in the capacity of "public servant" if we can call him that, or at least a man involved in public affairs.

Public men, political men, know their tastes are being scrutinized by many hundreds and thousands of people: enemies, friends, allies, rivals, rich and poor, voters and non-voters, et cetera. This is why powerful people who have the money hire image consultants and fashion consultants, so that they can have some degree of control over how people perceive them, and what non-verbal messages they are sending out into the world.

So: I put it to you that Podesta's Dahmer-inspired statue is not only a private interest or obsession, but a deliberately public display, one which says, however subtly and obliquely: this art incorporates some aspect of not only how I see the world, but how the organization I represent sees the world too.

Consider the images that we're familiar with from campaign ads, of people of all races working together on some worthy project, like a public garden or social welfare center, as they smile and nod and have serious discussions -- that too is a kind of political art, and it would send a certain kind of message if Podesta had those images on the walls of his home where he invited over donors.

But I put it to you that, if Podesta did have such images, he would seen as a shallow and ineffective man, since it is well known those kinds of images are for mass public consumption via TV and the Internet, and well-heeled donors have a "right" to expect to see a different side of the man to whom they are perhaps about to write a very large check. Such images would not only be pedestrian and innocent and boring: they would be ineffective.

Political fundraising is very much about charm, and so a smart and charming man as John Podesta certainly appears to be, would know that it would behoove him to have something more unusual than those kinds of political images on his walls. Anything would do, really.

Ansel Adams photographs would be enough: Podesta already has an "environmental record" so donors could reasonable conclude, if confronted with a bunch of Adams prints, that John really does love National Parks, et cetera, or at least that he wants the DNC's environmental agenda (and where that donor money is going!) to be seen as being at the forefront.

Politics is a subtle business. Few men, even if wealthy and handsome, are likely to bed as many good looking ladies if they go around asking "wanna fuck" to all of them (the old joke about the Russian hussar notwithstanding). In sex, as in politics, at least a bare modicum of "misdirection" is seen as more pleasing, and indicative that you are capable of some form of double entendre, or "hint" rather than bare-faced libido. Perhaps I am entirely wrong about this and have been doing it wrong all along! But I don't think so.

Politics is a subtle business and so people appreciate subtle signals in that world.

Let's consider the statue of the headless man divorced from any context. If you didn't know it was an echo of Dahmer's victim, a victim of cannibalism, you still already will form impressions of John Podesta the man and John Podesta the public charmer for the DNC, out to solicit big donations for his team.

It's a headless man. It's "tough" in a way. Podesta is a different looking man than say, Jesse Ventura, but this statue could, in the right light, help to show him as a "killer" -- someone who can get the dirty deeds done when necessary.

Or, in addition or alternately, it can convey pathos: the headless body is obviously contorted and evokes a complex emotional response: pain or fear or revulsion or sympathy or a mix thereof.

Or, if you believe as I do that John Podesta is a child rapist and cannibal, this artwork shows what he likes to eat. And shows he's willing to violate a particular and ancient human taboo. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Already we see something interesting about interpretations in this particular political context: although art can be interpreted in a variety of ways, it is limited along a spectrum. The work can not mean anything. It means an array of certain things, depending on who you are, and who you take John Podesta to be.

At the absolute least, we know it is unusual. And at the very least, you will conclude John is an unusual man: you're confirmed in something you already knew, since not every man raises millions of dollars for the Clintons and the DNC. At the very least, the statue is an undergirder for Podesta's political authority.

Let's leave aside too reports that certain potential donors have fled Podesta's home in shock when seeing this artwork and being told what it represents. No video record exists of such an exchange, after all. Let's stay focused on the art.

Any serious discussion of art is always, first to last, from cave paintings to video games, connected with a discussion of politics. Politics are those things we do in private and those things we do together and the relationship between them. Like the saying goes, you may not be interested in politics but politics is interested in you.

The things we make, cave paintings, statues, clothes, hairstyles, dance routines, these are, among other things, political statements about the world.

And when we are talking about art which is endorsed by a prominent political figure, a Roman senator, say, or a Venetian nobleman, or the mayor of Los Angeles, or the political showrunner in a major American political campaign, then we are talking about art which is used in that political context.

Those ancient cave paintings in Lascaux are saying, at a bare minimum: hunting is something we do, and it is important. Good or bad, maybe, but not indifferent. It emphasizes the centrality of hunting in their culture. And whoever the chief caveman or men or woman or women or both was there, it's safe to say they endorsed that political message, since they had to look at it all the time. When those cavemen got in "political fundraising" mode-- needed a bigger hunting party, say, or a couple of extra deer skins for winter, they could be assured that guests who were invited into that cave at Lascaux would understand that hunting was important, and valued, by those people.

What do the donors who view Podesta's headless man understand? The situation is similar: American political families and parties, like cavemen, need help to get what they want done. It takes a village, after all, and politicians' jobs are to forge such alliances.

Well, I've already said the bare minimum we can take away: Podesta is a strong man, an unusual man, with an emotional appreciation for art and life.

If you are extremely skeptical of all things "conspiracy" related, and refuse to accept anything less than full-motion video evidence of cannibalism and child rape as proof of something rotten in the state of Denmark, well, I suppose then we have to end here.

Such evidence has not yet surfaced. But note that already we have accomplished one thing: something unusual is going on here. Something powerful.

But let's say we're willing to take as fact (which some may dispute) that the statue is modeled on Dahmer's victim. Let's say we take as fact that Podesta knows the artist intended this 'echo' of a famous cannibalistic murder, and so we consequentially must assume Podesta is willing and, even eager, for his guests and potential donors to see and appreciate this artistic echo in the context of visiting his home and discussing American politics.

I would say the typical understanding of Jeffrey Dahmer's story is that he was a lunatic who indulged his depraved desires to kill and eat other human beings, and evidence was discovered of his partially severed and eaten victims in his freezer and elsewhere at his home. That's the bare facts of the case, nor do we need to delve more fully into them, assuming you accept those facts. (I don't think anyone claims he was framed!).

So, again, for the sake of argument, let's consider that work of art in a private context.

Let's say I had that statue. I could have many reasons for owning it--I might even hate the statue!-- but if I have it on display in my home at the very least it’s something I want to look at occasionally, something that means something important to me. We could have a wide range of interpretations of this decision to own this art work, including, I suppose, a humanitarian one. To support victims of cannibalism, per chance? That is barely possible but extremely unlikely as a valid interpretation, for one reason: it does not have a head.

With a head, we have a human being, or its simulacrum, and we identify with it as a human being on some level. Even as the famous statues of victims of the Irish potato famine on the Dublin shore urge us to identify with those political victims, a Dahmer victim with a head would help us to empathize, and we could think: what a poor man, to have been used so horribly. What a strange world we live in! Something like that.

Without a head, it's something else, something more abstract and less human. It becomes, perhaps, just an aesthetic form, akin to Greek statues missing heads and limbs where we still admire the artistry and the human form there captured.

But again: because we know (at this stage in our interpretation) that that figure depicts a victim of cannibalism, we can't have the same reaction as we would to a Greek statue. Most such statues are seen to be images of heroes and gods, with idealized human forms: celebrations of man's abilities and destiny. Even something like the Laoocon statue, where he is eaten by snakes, for instance, shows us a man competing with the elements. He is a victim, but he is fighting back.

The Dahmer statue is, by comparison, lifeless. It is the body the cops see when they show up. If you’re the cop who discovers Dahmer's apartment, assuming you're not yourself a cannibal, you're going to be disgusted. You're going to ask yourself: how could one human being do this to another?

So I think we have our second most important point here: Podesta's work of art is engaged in moral questioning. It does ask some form of that very basic question: how could one human being do this to another?

An important question. Not an easy one to answer. One that gets at the heart of the nature of war, for instance.

Already, look at all the potential good it is doing for Mr. Podesta, political fundraiser. We already knew he was strong and unusual. Now we see he's engaged with moral questions. The statue invites us to believe that he is invested in this political game at a level beyond mere wealth-accumulation and shows of status. He is interested in morality. He is interested in how people treat one another. And he is interested in when they do horrible things to each other.

But again, this is not, say, the Korean War memorial or the statue of Iwo Jima with the GI's planting the flag. Nor is it, say, the suffering body of a cancer victim. This is a private murder. One done for the perverse titillations of a disturbed man.

And remember: without a head it is difficult to identify with the victim on a human level. We're moved more quickly to some form of disgust: as in, "we are reduced to that."

So we could say there is a kind of nihilism involved here, already. That yes, these moral questions are important, of why men do these things to one another, but because "all flesh rots" and we are all mere assemblages of body parts, the question ultimately becomes unanswerable, and we are forced to conclude some form of "humans do crazy things and I don't know why."

But if that is our conclusion, why display this art so centrally? Why have a big "I don't know" statue in your living room?

Well, it's about ambiguity. Very plausibly, John Podesta is interested in indicating to his guests that he is extremely interested in ambiguous situations. Professional politicians appreciate subtle signals, remember. Even our First Oaf, Donald Trump, can occasionally try to make one. They're expected. And John Podesta is much more subtle that Donald Trump. Probably more subtle than Hillary Clinton as well: he works mostly behind the scenes, stepping behind the podium only when necessary, as when Clinton declined to attend her concession speech after her loss in November 2016.

Podesta is indicating to his audience that ambiguous situations (ambiguities very much interrelated to the problems of interpretation I am writing about right now), are of great interest to him.

Any student of American politics in the 20th and 21st century will likely be familiar with the phrase "manufacturing consent" and "muddying the water." Ambiguities are useful to writers like me, and they're even more useful to politicians. If you can say one thing-- the same thing, carefully crafted--to different audiences and have them reach different conclusions when they hear it, so much the better. Your time has been saved; your position consolidated; your audience grown.

We all know and lament the ambiguities inherent in public displays of political goals, political sentiments. We want politicians to say what they mean, but we also want to hear what we want to hear. The dual, competing nature of these desires leads naturally to ambiguity.

Podesta is saying, quite naturally: I'm with you. I live in this world. We don't always know why we do what we do. We don't always know what it means. I understand that. And I want to share that knowledge with you.

This is a very powerful position to take. He is demonstrating that he is an educated and urbane man, accustomed to making fine distinctions in a complex world.

Fine, fine! All from a statue of some headless guy!

Let's say, for the sake of argument, that John Podesta is a kind of saint. He enjoys playing with children in his private pool out of an overwhelming love for his fellow man, and wants to bring joy to children. It would be great if that were true; perhaps it is still barely possible.

In that case, I think it's very hard to argue that a man known to be a saint (no skeletons in his closet!) would be in a close working relationship with the Clintons, and I find it hard to see how this complex work of art, with all its ambiguities and strong imagery, would cooperate well with the public image of "innocent man." It doesn't, really. The art work -- this public symbol! -- rather says the opposite. It says: "I am compromised in interesting ways-- even if only in my mind. And I am okay with that."

This art work is a symbol of compromise: another strong and natural political position. The cavemen of Lascaux can't get help with the hunt for free; can't get extra deerskins for free. Trade is the backbone of politics.

So again, the statue is saying: I live in a world of compromise. A world of ambiguities. A world of difficult truths.

Rich people know something about that world. And some of them will appreciate a man who signals openly that he understands these things about the world they inhabit.

If we leave it there, we have already learned something interesting. This work of art cannot be innocent, because of who Podesta is. He is too smart for that; we are too smart for that; his donors are too smart for that.

This is the artwork of a compromised man. Even if he is no pedophile, no cannibal, this art work still signals his willingness to engage in-- and even his affection for -- this world of competing human motives, a world with no small amount of pain. Like Roman Emperors and their worlds, it is a subtle landscape, replete with contradictions and difficult truths. A world of monsters, and perhaps even angels.

Even if we never prove anything about Pizzagate; we have already learned a lot.

And reasonable people, when confronting such interesting signals of political compromise, might well be persuaded there is more to the story.