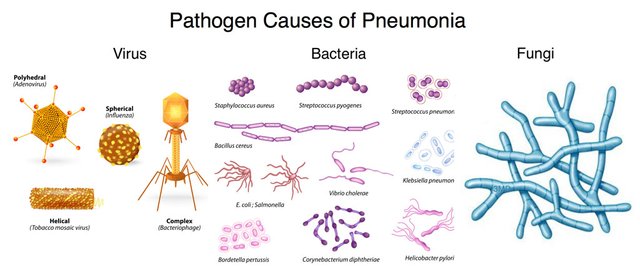

According to the germ-theory of disease, most common diseases are caused by pathogens―microbes engineered by nature and millions of years of evolution to prey upon larger multicellular organisms, such as Homo sapiens. By far the majority of these pathogens can be assigned to two principal categories: bacteria and viruses. A smaller number are identified as fungi or other microorganisms―eg unicellular protozoans. Among the diseases attributed to bacteria are tuberculosis, anthrax, tetanus, leptospirosis, and cholera. Those attributed to viruses include influenza, the common cold, covid-19, AIDS, and herpes. Fungal infections are blamed for problems such as athlete’s foot and ringworm. Malaria is attributed to the single-celled microorganism Plasmodium. African sleeping sickness is caused by another protozoan: Trypanosoma brucei.

But there are also a number of diseases which are attributed to both bacteria and viruses: eg pneumonia, meningitis, and bronchitis. In some cases a disease may even be assigned multiple causes: bacterial, viral, fungal, microbial, and environmental. Pneumonia is an example of a disease that has a variety of different causes, some pathogenic and infectious, some non-pathogenic and non-infectious. This makes it an ideal test case for germ theory:

Pneumonia describes an acute lower respiratory tract (LRT) illness, usually but not always due to infection, associated with fever, focal chest symptoms (with or without clinical signs) and new shadowing on chest radiography ... The many infective micro-organisms and pathological insults that cause pneumonia are listed in Table 5.1. ―McLuckie 51

In Table 5.1 we read:

Bacterial Infections that Cause Pneumonia Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia Coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetti, Chlamydia psittaci, Legionella pneumophila

Fungal Microbes that Cause Pneumonia Aspergillus, Candida, Nocardia, Histoplasmosis

Viruses that Cause Pneumonia Influenza, Coxsackie, Respiratory syncytial, Cytomegalovirus, Adenovirus

Protozoa that Cause Pneumonia Pneumocystis carinii, Toxoplasmosis, Amoeboesis

Non-Infectious Causes of Pneumonia Aspiration, Bronchiectasis, Cystic fibrosis, Lipoid pneumonia, Radiation

It is actually quite rare for a case of pneumonia to be attributed to a specific pathogen:

In the clinical situation, microbiological classification of pneumonia is not practical, since identification of the organism, even when possible, may take several days. Likewise, anatomical (radiographic) appearance (e.g. lobar pneumonia, which describes consolidation localised to one lobe; or broncho-pneumonia, which describes widespread, patchy consolidation) gives little practical information about the cause, course or prognosis of the infection. ―McLuckie 51

And when steps are taken to identify the pathogen, the results may depend on the method employed:

Aetiology

Identifying the causative pathogen in CAP [community-acquired pneumonia] is difficult and results vary with methodology (e.g. bacterial quantification), geography (e.g. the UK, Europe, the USA) and illness severity (e.g. community, hospital or ICU). No infective cause is found in 30–50% of cases, but in virtually all studies the most frequently identified organism is S. pneumoniae (20–75%). ―McLuckie 52

Let that sink in: even when laboratory tests are carried out to identify the pathogen responsible for the pneumonia, nothing is found in up to half the cases.

The History of Pneumonia

Pneumonia is not a new disease.

Pneumonia has been a frequent and serious human illness throughout recorded history. Histologic examination of Egyptian mummies (1250 to 1000 BCE) revealed hepatization of the lungs compatible with acute pneumococcal pneumonia. The disease was well known to the Greeks and Romans, and the symptoms and management (including a drainage procedure for empyema) were described by Hippocrates. Laennec described the pathologic changes and physical signs of pneumonia and pleurisy in 1819, and Rokitansky distinguished lobar pneumonia from bronchopneumonia in 1842. ―Feigin & Cherry 1:302

The name is Greek: πνευμονία, from πνεύμων, lung. And the symptoms of pneumonia were first described by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates in the 5th century BCE―assuming that the appendix to the treatise On Regimen in Acute Diseases was actually authored by him:

11. Peripneumonia, and pleuritic affections, are to be thus observed: If the fever be acute, and if there be pains on either side, or in both, and if expiration be if cough be present, and the sputa expectorated be of a blond or livid color, or likewise thin, frothy, and florid, or having any other character different from the common, in such a case, the physician should proceed thus: if the pain pass upward to the clavicle, or the breast, or the arm, the inner vein in the arm should be opened on the side affected, and blood abstracted according to the habit, age, and color of the patient, and the season of the year, and that largely and boldly, if the pain be acute, so as to bring on deliquium animi, and afterwards a clyster is to be given. But if the pain be below the chest, and if very intense, purge the bowels gently in such an attack of pleurisy, and during the act of purging give nothing; but after the purging give oxymel. The medicine is to be administered on the fourth day; on the first three days after the commencement, a clyster should be given, and if it does not relieve the patient, he should then be gently purged, but he is to be watched until the fever goes off, and till the seventh day; then if he appear to be free from danger, give him some unstrained ptisan [tisane], in small quantity, and thin at first, mixing it with honey.

If the expectoration be easy, and the breathing free, if his sides be free of pain, and if the fever be gone, he may take the ptisan thicker, and in larger quantity, twice a day. But if he do not progress favorably, he must get less of the drink, and of the draught, which should be thin, and only given once a day, at whatever is judged to be the most favorable hour; this you will ascertain from the urine. The draught is not to be given to persons after fever, until you see that the urine and sputa are concocted (if, indeed, after the administration of the medicine he be purged frequently, it may be necessary to give it, but it should be given in smaller quantities and thinner than usual, for from inanition he will be unable to sleep, or digest properly, or wait the crisis); but when the melting down of crude matters has taken place, and his system has cast off what is offensive, there will then be no objection. The sputa are concocted when they resemble pus, and the urine when it has reddish sediments like tares. But there is nothing to prevent fomentations and cerates being applied for the other pains of the sides; and the legs and loins may be rubbed with hot oil, or anointed with fat; linseed, too, in the form of a cataplasm, may be applied to the hypochondrium and as far up as the breasts. When pneumonia is at its height, the case is beyond remedy if he is not purged, and it is bad if he has dyspnoea, and urine that is thin and acrid, and if sweats come out about the neck and head, for such sweats are bad, as proceeding from the suffocation, rales, and the violence of the disease which is obtaining the upper hand, unless there be a copious evacuation of thick urine, and the sputa be concocted; when either of these come on spontaneously, that will carry off the disease.

A linctus for pneumonia: Galbanum and pine-fruit in Attic honey; and southernwood in oxymel; make a decoction of pepper and black hellebore, and give it in cases of pleurisy attended with violent pain at the commencement. It is also a good thing to boil opoponax in oxymel, and, having strained it, to give it to drink; it answers well, also, in diseases of the liver, and in severe pains proceeding from the diaphragm, and in all cases in which it is beneficial to determine to the bowels or urinary organs, when given in wine and honey; when given to act upon the bowels, it should be drunk in larger quantity, along with a watery hydromel. ―Hippocrates, Appendix to On Acute Diseases 11 (Adams 324–325)

The author of this treatise regarded pneumonia as an old disease:

Acute diseases are those which the ancients named pleurisy, pneumonia, phrenitis, lethargy, causus, and the other diseases allied to these, including the continual fevers. ―Adams 283

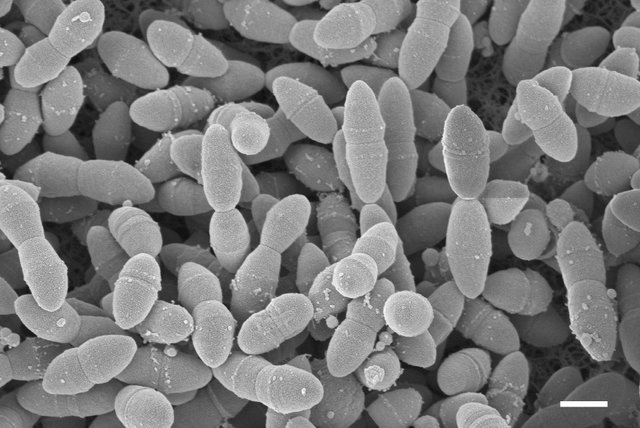

Streptococcus

The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae is said to be the commonest cause of the disease. But is Streptococcus pneumoniae actually pathogenic? This bacterium is commonly found:

residing asymptomatically in healthy carriers typically colonizing the respiratory tract, sinuses, and nasal cavity. However, in susceptible individuals with weaker immune systems, such as the elderly and young children, the bacterium may become pathogenic and spread to other locations to cause disease. (Wikipedia)

This is a common feature of so-called pathogens. When they are found in diseased tissue, they are identified as the pathogens that caused the disease. But they are often found in the tissues and organs of healthy individuals without causing any disease. Is there really such a thing as an asymptomatic carrier? Why would nature evolve a pathogenic organism that can only prey upon animals whose immune systems have been weakened by age or comorbidities? How does an organism that is found in the tissues of healthy individuals become pathogenic?

The diagnosis is usually tailored to fit the circumstances, whether this makes sense or not:

The bacterial “pathogen” is present and the patient is ill: Bacterial Pneumonia.

The bacterial “pathogen” is present but the patient is healthy: Asymptomatic Carrier.

The bacterial “pathogen” is absent but the patient is ill: Viral Pneumonia.

In this article I have taken pneumonia as a typical example of an infectious disease, but I could just as easily have chosen any one of a dozen or more common diseases. Louis Pasteur’s simple model of the germ theory, in which each infectious disease is caused by a specific pathogen and obeys Koch’s Postulates, has never resembled what doctors actually observe in the field. But did Louis Pasteur really claim such thing? It is only fair to go back to the primary sources and read what Pasteur actually wrote about germ theory. And that is what we will do in the next article.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Francis Adams (translator), The Genuine Works of Hippocrates, Volume 1, The Sydenham Society, London (1849)

- Ralph D Feigin & James D Cherry (editors), Feigin & Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Sixth Edition, Volume 1, Volume 2, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia (2009)

- Angela McLuckie (editor), Respiratory Disease and Its Management, Springer-Verlag, London (2009)

- René Vallery-Radot, La vie de Pasteur, Twenty-Fourth Edition, Librairie Hachette, Paris (1923)

Image Credits

- COVID-19 Poster: © 2021 Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Fair Use

- Pathogens Believed to Cause Pneumonia: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- A Woman Suffering from Pneumonia: Karl Heinrich Baumgärtner, Kranken-Physiognomik, Dr Madaus & Co, Radeburg (1838 : 1929), Wellcome Images, Public Domain

- Hippocrates Refusing the Gifts of Artaxerxes: Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (artist), Museum of the History of Medicine, Paris, Public Domain

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: © Muhsin Özel, Gudrun Holland, Rolf Reissbrodt (electron microscopists), Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Creative Commons License

- Louis Pasteur: Paul Nadar (photographer), Public Domain