What makes politics a reality for you? What grounds it in a moment when you can say, “Okay -- this is where we are?” Or, to put this another way: why did Iowa Congressman Steve King think it was okay to celebrate the expulsion of a DREAM student by photographing a glass of beer while seeming to express deep, dismissive contempt regarding the deported student’s academic potential? Why did activists in Portland think it was okay to all butimmediatelycall for the resignation of Ted Wheeler after he assumed office?

This is an essay about politics, what have come to be known as ‘information silos,’ and art. It’s a meditation on how to go about making all three better, an attempt to fracture the mobius strip that passes itself off as civic engagement, that all but blends itself into it, and it begins with this question: is every act a textual act?

The question is an attempt to ask the obvious, to seek out the countervailing and the creaky, to engage with the fact that there were a thousand Flappy Bird think pieces were written, edited, and published, and no one seemed to bat a collective eye, nor even take note of the fact that citing something like a sudden outpouring of Flappy Bird think pieces is worth weighing up in any serious way, that -- even if there are enough people who feel like they know better and express as much cynically, humorously, or knowingly -- the structure beneath Flappy Bird is still in place, still exists, and the problem related to that structure still exists.

What do I mean by a ‘textual act?’ What is the ‘problem?’ Why does it persist? I’m suggesting that to treat something as a ‘textual act’ is to say that any action taken at any point is worthy of being treated as an academic text, as something capable of yielding as much exegetical output as there is exegetical energy put into the text. I am using ‘the textual act’ as a piece of synecdochal coinage because the internet is broad, and it’s worth hitting on a variety of points about the internet simultaneously. If I were to spend my energy focusing on one thing, it would be like playing a game of whack-a-mole. Something would arise somewhere else.

So: if I lift a glass of water and place it back down on the table from which it was raised, how much of that is worth segmenting into various data points of information? Is it worth thinking about a sociological read of raising the glass of water? Should we talk about the future of water security? (We should, but what about my lifting a glass up and down compels us to talk about it?) What part of lifting up a glass of water and putting it back down upon the table tells us about the news and the talking points of the day? In other words: how can move from saying -- as David Foster Wallace once put it -- ‘This is water’ to ‘This is how we liberate ourselves from water?’

You can’t argue with the realness of what’s being treated as a textual act, because to read a text requires a text -- that is, something real. It’s right there. It’s right in front of you. You can’t argue with the facts. The glass is in your hand. You’ve lifted it up, and then -- after a dramatic pause -- you’ve returned it to a surface. And you can’t really argue with the argument either: not only is it hooked into something that’s real, it’s done in a compelling, intense way that’s saturated in the text itself.

Where does that strategy of engagement take us?

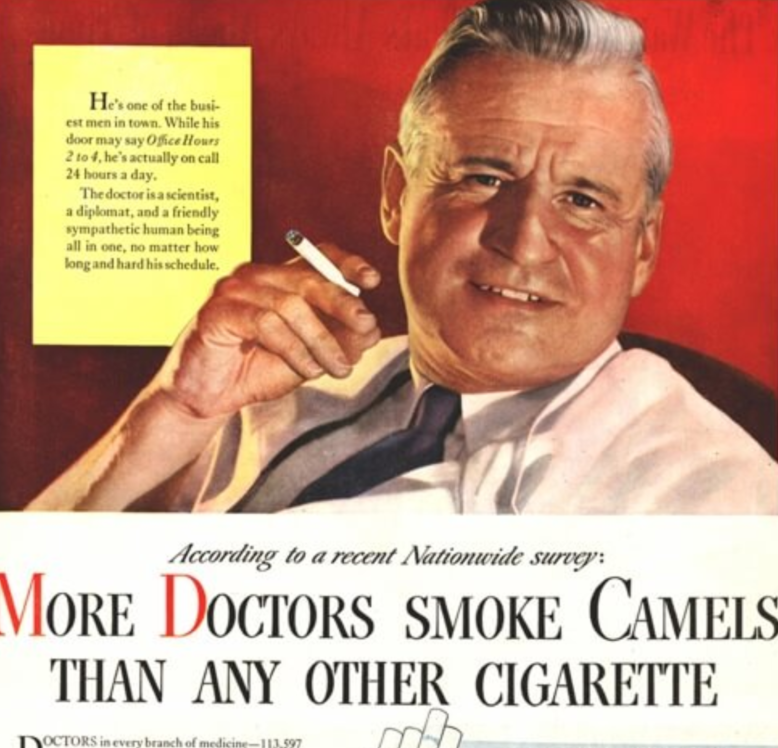

Let’s begin in a lateral place: what is happening when people decide to call out someone like Dave Chappelle for telling a joke that doesn’t quite fit -- to the point where someone calls it transphobic? Is it a matter of a changing world? What happens when we look at a routine of his and someone responds with “Black and brown women have been the victims of misogyny and systemic racism for centuries?” How can we seemingly seem to respond to something designed to open the aperture in our lives by insisting that the aperture close? Does that mean that Seinfeld was right to complain about performing on college campuses, and are students right to complain about Seinfeld in return? Is a comedian right to complain about his act being filmed, saying that they need to have the chance to work before a crowd unfiltered? That they now have to learn how to jump over the hurdles of both cameras in the crowd and a new political culture taking shape? And if comedians are the allies that they claim to be -- and I believe that they are (think of how musicians lent fissures to the walls of apartheid in South Africa or of the history of engaged literature; art already knows how to take responsibility for the world and dream of the future) -- then why are they being cast aside as such?

If the point of art as seen from the perspective of Theodore Adorno is to pursue a certain kind of unhappiness to highlight the gap between what is and what could be (see: Saunders, George; Wire, The), then wouldn’t one pause for a moment in encountering a culture that seems to exhibit signs of either unhappiness or displeasure? Consider how often Jonathan Franzen has been dragged. Consider the response to Lionel Shriver. Consider the time when The Oscars were dragged. Consider the request that a painting be destroyed. Consider the campaign to ‘Cancel Colbert’ after a joke of his was taken out of context -- and the kind of treatment the woman calling for Colbert’s cancellation received in return. None of this seems to be done out of joy. Instead, this was done out of urgency. But urgency for whom? In the name of what?

“Artworks tend a priori towards affirmation,” Adorno wrote in Aesthetic Theory, adding --

The clichés of art’s reconciling glow enfolding the world are repugnant not only because they parody the emphatic concept of art with its bourgeois version and class it among those Sunday institutions that provide solace.

Why are we reminded so often of our repugnance? Is it possible to defend the a priori nature of art (as well as its capacity in generating empathy and exploring nuance) while still maintaining a healthy, agile concept of the socio-economic concept of the world without perpetually and explicitly twinning the two together?

One answer for our sense of our own repugnance is the obvious one, the one that called upon Toni Morrison to look at the work of the Africanist presence in the works of Willa Cather, Edgar Allen Poe, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, and Ernest Hemingway in Playing in the Dark.

“As a disabling virus within literary discourse,” Morrison writes, “Africanism has become, in the Eurocentric tradition that American education favors, both a way of talking about and a way of policing matters of class, sexual license, and repression, formations and exercises of power, and meditations on ethics and accountability.”

She continues --

The literature of the United States, like its history, represents commentary on the transformations of biological, ideological, and metaphysical concepts of racial difference. But the literature has an additional concern and subject matter: the private imagination interacting with the external world it inhabits.

But looking at literature and art like this -- including a particularly grim, dispiriting thread that runs through Hemingway’s To Have And Have Not -- also depends on the nature of how we ultimately decide to interpret (and live with) the notion of a national sin -- and not through a matter of denial, a matter of sailing along as if it never happened at all.

That being said: are we offering up sufficient repentance for slavery and racism’s subsequent transmutations when we seek to shape the landscape to re-render Jonathan Franzen’s name the literary equivalent of Mitt Romney’s “Binders Full Of Women?” How does going after a painting square with the idea of fighting to ensure that -- if a school has at least one black teacher -- “the black students assigned to black teachers graduate high school at higher rates [and] were more likely to take a college entrance exam?” Of fighting to ensure there are policies that monitor suspension rates of minorities in school districts so as to keep an implicit racial hand from showing itself and needlessly punishing those who (in all probability) shouldn’t be punished? Of reminding people of the historical context of how a slave-owner would be punished if he killed a slave, but a cop might not be charged if he killed someone like Tamir Rice? (And how Campaign Zero is therefore worth emphasizing and reemphasizing again and again?) Of passing a local ordinance to give a headstone to slaves whose bodies reside in our unmarked earth without a headstone to call their own? (Consider the work of The Periwinkle Initiative here.) Of fighting to institute a tradition -- perhaps in conjunction with the French -- where a voudou ceremony is enacted once a year for a certain number of years, where the spirits of the first enslavers who arrived on San Domingue come from France to apologize to the loa named Agwé? Of articulating and overcoming the economic legacy of racism?

.

Photo via

Photo via

Perhaps the potency of the issue here is aligned with the fact that digital natives speak to the identity of the matter first, where their identity is the size of the entire internet, and then work backwards into the physical world: if you uploaded every American’s brain to the internet and downloaded it into an android you’d created, who’s to say it wouldn’t look like what we see before us online today?

“I do not know what white Americans would sound like if there had never been any black people in the United States,” James Baldwin once wrote in an essay on Black English in 1979, “but they would not sound the way they sound.” But how is any of this dialogue different from what Norman Mailer encountered on the campaign trail when he was running for Mayor in 1969? How is any of what we've seen recently different than something like this?

Before [Jimmy] Breslin spoke, a boy in the audience told him that he must denounce a teacher who was present as racist, or he would not be allowed to speak.

And what would make for an appropriate transpositive joke here, anyway? Would you talk about how former North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory first tried to pass a bill banning large harps with large googly eyes pasted on them from bathrooms, thinking that they were somehow a threat, too? And why hasn’t Patton Oswalt’s joke about how some of this has been framed received more attention?

Above: Patton Oswalt on the difference between words and intent in the Netflix special, “Talking For Clapping.”

“It’s insulting to artists as aesthetic thinkers to impose the bluntest political readings on their work without considering the ways in which their choices affect the expression of their ideas,” Alyssa Rosenberg recently wrote in The Washington Post, a sentiment which should be read in conjunction with Jaime Weinman’s look at how we talk (and have spoken) about film over at Vox. “And it’s also insulting to artists as political thinkers to pretend that their aesthetic decisions aren’t in support of anything.”

Above: Nina Simone in interview, which also features here.

So you are a Digital Native. You are interested in art. You are interested in politics.

What is your strategy for dealing with perception management? Choice architecture? Confirmation bias? Anchoring bias? An availability heuristic? What about information bias? Recency? Survivorship bias? Zero-risk bias? Do you have a plan for dealing with any of these? If not, why not? When’s the last time you spoke with someone else about this?

And, speaking more broadly, what has perception management done for us lately? (Besides give us Edward Snowden, or -- to extrapolate from Clint Watts’s testimony to the Senate Select Committee On Intelligence ever so slightly -- Donald Trump?) What has been built into choice architecture today? How do you reckon that combines with the Dunning-Kruger effect? (What do you think Russia thinks about this? The United States? China? Edward Snowden?) When’s the last time journalism called this out en masse? (Or -- indeed -- pushed through this mobius strip of a problem on their way towards something approximating the truth?) How long will Bayesian networks still leave us with ‘truth?’ (A related, abstract question: can you surprise enough layers of ‘if, then’ argument?) Will people heading online always only seek what they want -- and nothing more? What is someone who’s read Guy Debord to do? Seek Thomas Pynchon and MF Doom out and have perpetual over-the-shoulder drinks in an empty, windy bar somewhere in the woods of Washington state? Is it possible to oversaturate a network with ‘humanity?’ Is it possible to rearrange these networks so that the textual act switches to a broader contemplative daydream?

The textual act is a safe enough behavioral bet that Facebook was paying individuals to live stream on its site and Donald Trump feels free to tweet whatever he wants, whenever he wants. Fifty years prior, the computer program Eliza seemed to be a success merely because it parroted sentences back to the individual who typed questions into it. (Why was that moment between sitting down in front of Eliza and engaging with Eliza such a compelling choice? How many people noticed the moment between the before and after?)

Is there a danger here in framing that initial behavioral impulse with the internet and internet architecture as something resembling early cultural engagement with rock’n’roll, reading novels, and the like? Is there a way in which early socio-cultural engagement with novels or plays is distinct from socio-cultural engagement with what the internet and the internet architecture has been for the past ten-to-fifteen years? Ten years ago, I would have agreed with the first question wholeheartedly; now, I’m a little bit more cautious. I wait.

Julio Cortazar once wrote in 1976 that “Nothing seems more revolutionary to me than enriching the notion of reality by all means possible,” and it’s here where I think I draw my difference with the textual act of the moment, as the textual act seems to follow a worryingly predictable linear line. And, not only that, but our responses to the textual act seem to follow a worryingly predictable loop-de-loop as well. Mitt Romney has binders full of women? Dismissed. Ed Miliband once ate a bacon sandwich in a bit of a funny way? Well, he’s just a little bit weird, isn’t he? Never mind how well Miliband was versed on policy. Never mind how Mitt Romney seemed to express concern about the gap between the Hillbilly Elegy voters and the lawyers in The White House before his first debate in the documentary Mitt. We have seen something grounded in reality. We’ve invested something in that. Who are you to deter us and say otherwise? Who’s to say that the medium by which these engagements occur has any degree of responsibility in the matter at all? I’m the responsible one when I drive. The other driver is the problem.

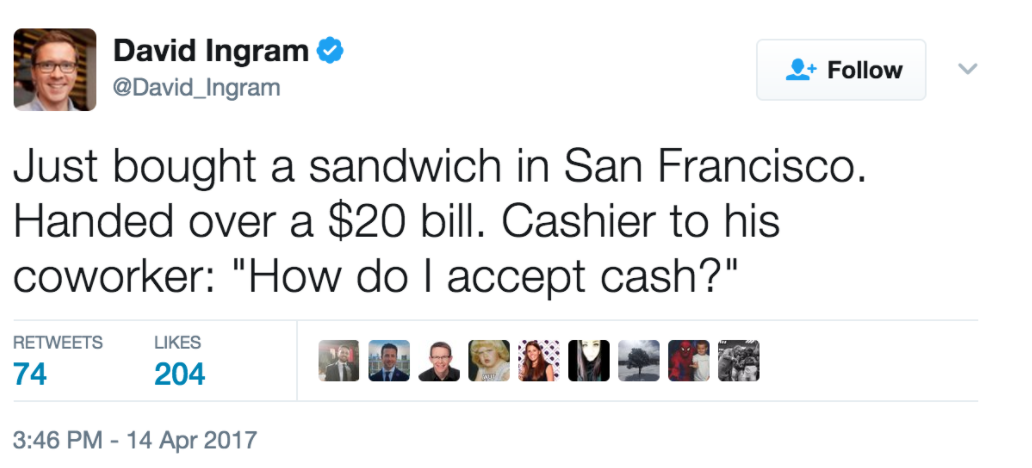

But, here’s the thing: to explore political choice on the internet means exploring what feels like political choice inside a particular business model that is much more canny at keeping you connected to the framework of its business model than television; with television, the high water mark of cleverness can be in watching an ad on television make fun of the fact that it’s an ad on television to keep you watching, the key difference between the two being that you don’t ultimately carry your television with you in your pocket wherever you go. You don’t turn on the television you carry with you in your pocket 150 times a day. And though this is well known amongst those who look into the matter, it’s worth emphasizing again how much more quickly lies travel on the internet than the truth, as well as that thing called anger.

And that’s why I don’t agree with the binary political divide that’s making itself manifest in relation to college campuses across the country either (which receive attention but aren’t really part of a cross-campus trend, as PEN America notes): when Noah Rothman decries “Highbrow Fascism” in Commentary Magazine, he’s not only ignoring the harm of certain ideas being broached -- though it does raise something an interesting sidebar: how contagious is a Richard Spencer in today’s web-based world? To what degree can that be quantified? (Will the ADL’s soon-to-be-constructed center be able to provide us with any answers?) -- but he seems to be ignoring the broader architecture of the dialogue in which this is occurring as well. On the other side of the equation, when The Wellesley News writes of free speech, they seem to elide over how they came to the conclusion that shutdowns are more beneficial to the campus than engagement, education, outreach, counter-arguments, counter-protests, and the like, jumping to the end of a scenario out of emotions we cannot necessarily begin to presume.

“With little comment,” Jeffrey Herbst writes in a white paper published by the Newseum, “an alternate understanding of the First Amendment has emerged among young people that can be called ‘the right to non-offensive speech.’

He continues --

The approach to diversity in many elementary and secondary schools seems to be little more than “Don’t say things that could hurt others.” While this might be very good life advice, students have come to interpret it as curtailing the First Amendment.

Further data in the white paper seems to indicate that a healthy majority of those at university campuses believe in creating “an open environment” and that “colleges should not restrict political speech.” Data also indicates that a cross-party political majority also believes in some form of self-censorship as well.

A figurative cat’s cradle exists, which means … what? How concerned should we be that these instances are playing with the idea of an absolutist defense of free speech?

It’s also worth noting that the frame of “a textual act” is a self-evident failure by nature of its singularity. One size does not fit the intellectual all here. I could not mold the phrase “the textual act” and wear it as a hat as I wandered about town -- even if there was a part of me that would not mind if this happened to happen. But this frame is useful in asking certain questions, like, “If every act is a textual act, then what is the textual act where an elected representative and someone who voted for a U.S. Senator share a unifying moment? What does it mean to move beyond ‘the textual act?’ Can you ever liberate yourself from water? Would you want to? What would be the consequences, if you did?”

I do not intend to disparage the liberal political tradition (or project) or seek to advocate a certain kind of anemic moderation. I can’t stress that particular aspect of this enough, as a lot of my commentary here will be interpreted as something internecine, so, again: I want you to believe someone when they talk about racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, or Islamophobia. I want you to believe someone when they talk about sexual assault. I want you to believe someone when they talk about representation and a diversity of voices. I want you to ask yourself what white privilege means and find the ability within yourself to avoid offering up an answer that could very well see itself appear in the eventual follow-up to “Get Out.” I want you to think of potential answers to the current articulation of the problem of race yourself without asking Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, or DeRay McKesson to solve all problems related to race. I hope you regularly use the internet as a tool to seek out voices you’ve never heard before.

But I don’t want you to uncritically believe the internet as a vehicle of that representation.

Arguments can be (and are frequently) hollowed out. Coalitions are hard to build. To go online in America means something different here than it does in the rest of the world. (To get a better sense of what social media means across the world, I’d recommend reading the Why We Post books put out by University College London -- or simply asking a friend who lives in another country.)

But place still matters. Community still matters. Neighbors matter. Time matters. Wisdom matters. Listening matters. Attacking “information silos” deserves much more than what we’ve been able to bring to the table thus far, and -- based on some of what I’ve outlined here -- I worry that treating everything as a textual act might not help.

This is not a criticism of the internet. This is a criticism of how you are using (and have been using) the internet. (And there’s evidence out there to back this up, too: “A recent study based on Facebook data found that algorithms play less of a role in exposure to attitude-challenging content than the individual's own choices.”) This is my way of saying that I want you to remember that for all the unconscious drifting the internet implicitly and explicitly encourages, you can grow, and that you are someone who is capable of growing. (It’s also worth noting that this entire piece was written well before The New York Times Magazine profile of E. Williams went live.)

Here’s an extreme example of something to bear in mind if we don’t grow: if we find that in revisiting the analysis of Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui in Unrestricted Warfare that what was posited within the book still holds true and that -- to draw one lesson from those pages -- the battlefront is everywhere (that it has “re-invaded … post-modern, post-industrial … society in a more complex, more extensive, more concealed, and more subtle manner”), as -- for instance -- Vladislav Surkov posited in Putin’s name in the short story “Without Sky,” then a crucial civic organizing aspect regardless of whether or not we have war or peace or this thing that attempts to dance between the two going forward will be in breaking the pernicious effects of the ‘information silo’ apart. (At the state level, Anne-Marie Slaughter’s The Chessboard And The Web is emphatic about the need to encourage greater strategic thinking here, and -- at its broadest -- it is not a call we should ignore.)

So if we insist on behaviorally prioritizing the ‘internet space’ first -- i.e., if we check our phone the moment we roll out of bed in the morning -- then how might we go about breaking down an ‘information silo?’ One study of 14 million users suggests that self-selection begins after either someone’s fiftieth comment or fiftieth ‘like,’ so perhaps the algorithms that enable us to catch up on what we’ve missed or reflect back to us posts we’ve already expressed an interest in seeing could adjust ever so slightly to also share something we don’t agree with or like as well, and not -- perhaps -- push forward the idea that to share something is to agree with something, because if the diversity of content on Facebook is filtered by friend choice and filtered further still by what friends engage with, what’s to keep engineers from adding something a little bit more proactive and diverse than a ‘news feed?’ What’s to keep Spotify from making it a little bit easier for users to listen to the four million songs on Spotify that have never been played? If people like educated nudges, what’s to keep them from liking this? If people believe in the idea of operating on the internet with a certain degree of personal agency and still like nudges that won’t insult their idea of personal agency, then what is the delay? What’s the hold up?

And this isn’t just about the fact that people seem to be trapped inside information silos, but that we also seem to have been having the same conversation within the context of these so-called information silos every day for years. Replying to Corey Stewart now for defending confederate statues is no more interesting than it was when Gawker took a pointless shot at David Simon or when a writer who was part of the Gawker network decided to change Justine Sacco’s life.

“Shifts of power and control are going on all the time,” Ursula Franklin wrote in The Real World Of Technology. “Any task tends to be structured by the available tools. It can appear that the available tools represent the best or even the only way to deal with a situation … If you have a particular type of kitchen equipment, you begin to slice and dice as you never have done before. Other means of food preparation become less attractive and you may eventually forget about them.”

“During the US 2016 presidential election period,” Helen Margetts, the director of The Oxford Internet Institute, wrote in Nature, in an article we’ve already cited, “around 128 million people across the United States generated 8.8 billion likes, posts, comments and shares related to the election on Facebook alone.”

She goes on to warn us that --

Speculation over the existence of echo chambers, and their interaction with other pathologies of social media such as fake news, vastly outpaces any experimental studies of their existence.

In other words: we are both flying blind and committing a disservice to the dialogue at hand and the issues at play because of this. When’s the last time someone with a significant internet-based platform who said or believed in the idea of ‘Blue Lives Matter’ took the time to read President Obama’s article on criminal justice reform in the Harvard Law Review and then offer up comment? How do they feel about the fact that “With just 5% of the world’s population, the United States incarcerates nearly 25% of the world’s prisoners?” Or the fact that --

The federal government spends more than $7 billion a year to house prisoners, nearly a third of the Department of Justice’s budget and a figure that crowds out spending on other critical public safety initiatives?

Or would this strawman throw up their hands, say that the country needs more law and order, and move on, letting Jeff Sessions invent facts where and when he pleases? (Regardless of the recommendations made therein, like the fact that evidence seems to back up a lowering of mandatory minimums, the merits of the Smarter Sentencing Act, how correctional education programs really do seem to have an impact in lowering recidivism, how one might circumnavigate employment discrimination (or discrimination in education) based on prior convictions, and more?) Would activists swirling about the edges of the left look at the issue themselves, call America a fascist police state, and then move on, too? What would the constancy of life impose upon their particular sense of thinking the issue through?

Above: a screenshot from the music video for St. Vincent’s “Digital Witness” paired with the lyrics of Arcade Fire’s “We Used To Wait.”

Above: a screenshot from the music video for St. Vincent’s “Digital Witness” paired with the lyrics of Arcade Fire’s “We Used To Wait.”

15% of Americans still aren’t online. (That’s over 47 million Americans.) 68% of Americans use Facebook. 20% of Americans use Twitter. And, per Eszter Hargittai of the University of Zurich, the woman from whom I’m drawing these statistics -- socio-economic status determines who adopts these systems in the first place. In other words: part of the problem isn’t just about information silos or a lack of data -- it’s about seeming to oversample the data we already have based on class, too. (Think of how Chris Arnade’s work stands out. Think of how often news stories about Uber never seem to square themselves with the access Uber affords those living in or near the poverty line, especially in areas with terrible transportation infrastructure. Think of how -- in 2013, at least -- we read about statistics like how “all of Africa combined contains only 2.6% of the planet’s Wikipedia articles despite having 14% of the world’s population and 20% of the world’s land.”)

How does a culture filled with digital-first natives seek to reach 47 million Americans in political dialogue and discussion? Is there a plan? If not, why not? How does a culture of digital-first natives plan to listen to those 4 million songs on Spotify that have never been played before? Do they even realize they’re there?

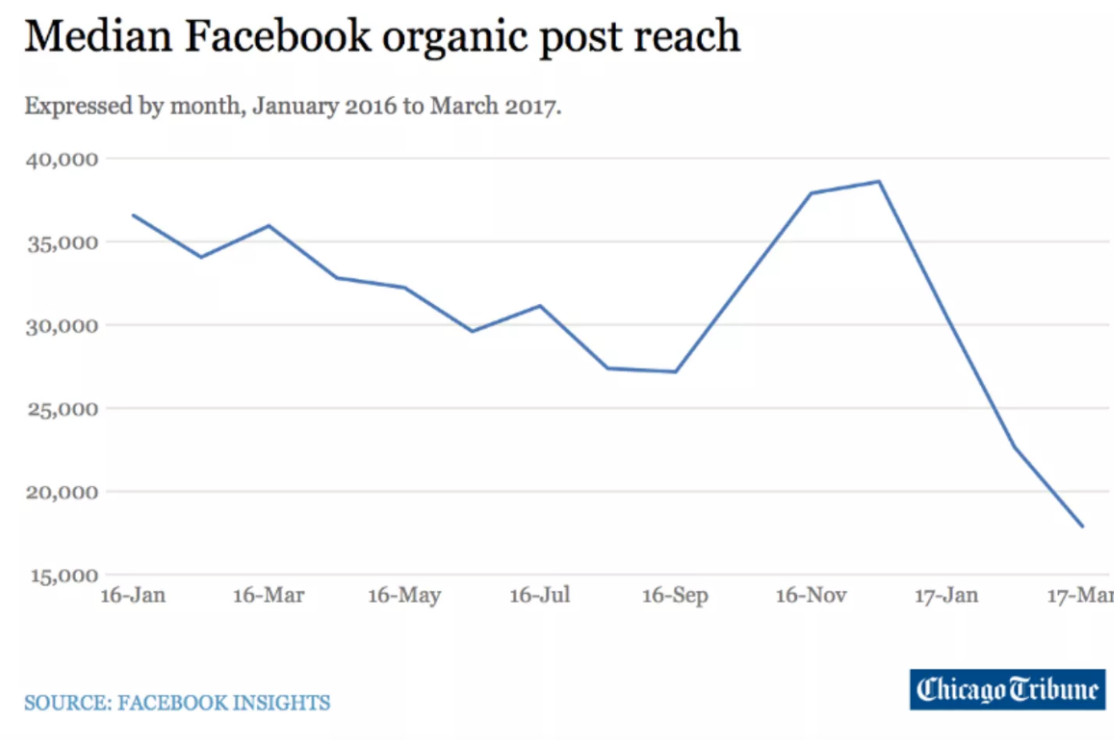

And how well does all this square with the state of our democracy? Shall we rise and offer up an oily reassurance of the United States’s capacity to change, as Christopher Buckley did in an Oxford Union debate with James Baldwin? Shall we spend one day a week clicking on the banner ads that appear on The New York Times and The Washington Post? Should we look at the data coming from The Chicago Tribune and pressure Facebook into changing their algorithm? (Or start work to encourage more ways web users can naturally head to newspapers beyond through something they see on Facebook?)

Via Poynter.

Via Poynter.

How we behave online doesn’t necessarily have a direct bearing on how well journalism thrives in our country, but, as the Columbia Journalism Review notes, “Journalism with high civic value—journalism that investigates power, or reaches underserved and local communities—is discriminated against by a system that favors scale and shareability.” The report continues --

If news organizations are to remain autonomous entities in the future, there will have to be a reversal in information consumption trends and advertising expenditure or a significant transfer of wealth from technology companies and advertisers.

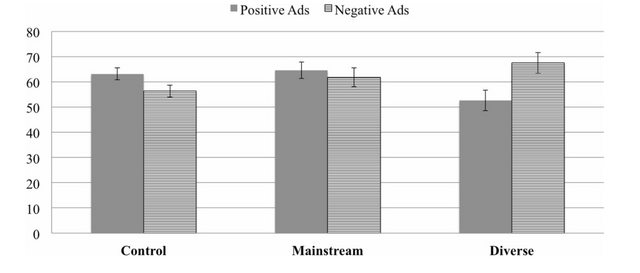

Chart via LSE: “Effect of media environment and Ad Tone on affective polarization.”

Chart via LSE: “Effect of media environment and Ad Tone on affective polarization.”

The choice of how our journalism functions going forward (and, therefore, how it functions as a factor in our democracy) won’t just be depend on our habits of information consumption (and how it factors into polarization); the availability and number of all the different ways in which someone might be able to dislike someone else politically seems like it will have an impact going forward, too, and that is something that calls for a much more immediate sense of online media literacy that goes a step beyond being something like an explainer akin to Vox or a shortcut around clickbait like ‘Saved You A Click.’

What happens when you combine the idea of a textual act with the worlds of how you experience politics on a college campus online, how you experience journalism online, how you experience the discussion about race online, and how you experience art online? To what degree are you prepared to think each particular issue through? To what degree are you prepared to think about them holistically? How would each of those serve as a training ground to prepare you in case you encountered someone spreading false information?

In mapping out the tweets connected to the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, Kate Starbird noticed that the 8th most re-tweeted account connected to the hashtag #oilspill contained a few interesting particularities -- first, it was (in effect) a conspiracy theory account consistently trafficking in politicized fear-mongering; secondly, it was not connected to the network of local twitters and actors at all. “These alternative narrative rumors rarely resonated within crisis-affected populations,” she later noted (as someone who was at the Boston Marathon bombing, I was surprised when I found myself arguing with someone from Al Jazeera that what had happened wasn’t the result of an electric generator blowing up), but the danger of disinformation campaigns is that it leads to “crippled epistemologies,” which can create mindsets that won’t make great decisions when it comes to engaging with journalism, college campuses, race, and the like.

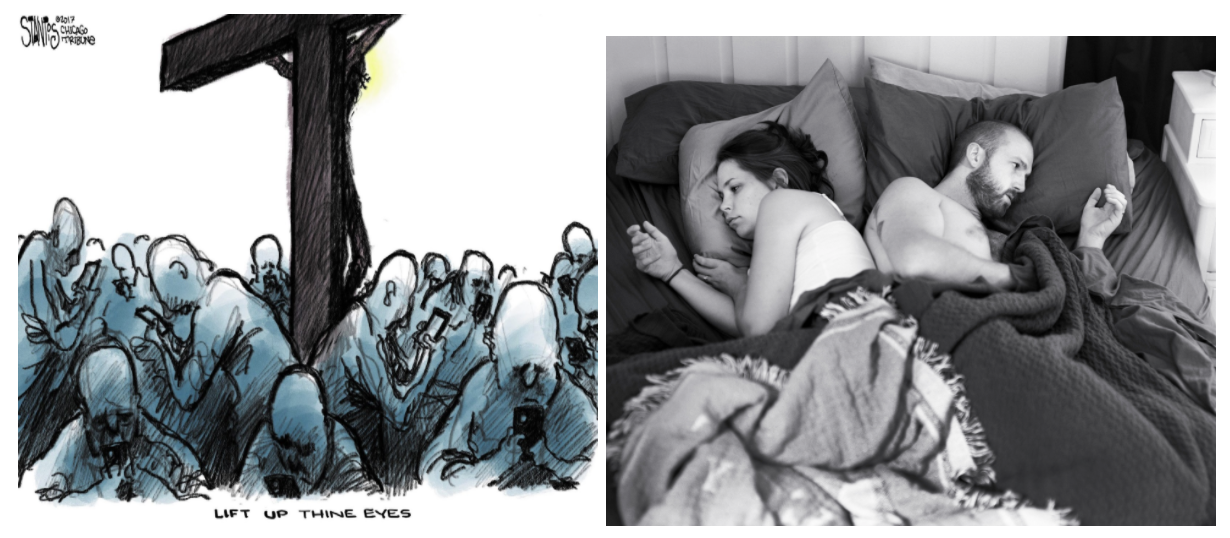

On the right: an image from Eric Pickersgill’s “Removed.”

To be aware of the way in which the internet functions as a tool in our democracy requires a sense of the way in which the internet threads its way through our lives. We see it in our art, our politics, as a way to express our sense of self, and more. In sketching the essay in the way that I’ve done, in looking at how the internet threads itself through our lives, I hope I’ve been able to provide a rough outline as to how we might go about making our collective lot a little bit better.

Disclaimer: I am just a bot trying to be helpful.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks, Twitterbot.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit