Hebron

In Hebron I worked with ISM, a human rights and solidarity organization of Internationals and Palestinians. The Palestinians organize the work, and the internationals support it. ISM is fully committed to the philosophy of non-violence, and all volunteers are taught the concepts and are trained in the practice of non-violence.

Israel still doesn´t like the organization, portraying its members as radicals.

I have often heard the question, asked by Europeans and Americans: "Why is there no Palestinian "Ghandi"?"

The answer is that there are actually many, many Palestinian "Ghandis," and there have been for many years--people committed to a non-violent struggle for justice and equal rights. Most of those Palestinian "Ghandis" have spent years in prison.

You just don't hear about them in Western media outlets because until very recently, western media preferred to portray Palestinians as violent, and Israel's state-terrorism as "self-defense".

Hebron (Al Khalil in Arabic) is, according to Islamic, Christian and Jewish tradition, the place where the patriarchs Abraham and Isaac, and their wives Sarah and Rebecca, died and were buried.

Hebron (Al Khalil in Arabic) is, according to Islamic, Christian and Jewish tradition, the place where the patriarchs Abraham and Isaac, and their wives Sarah and Rebecca, died and were buried.

The site of their tomb is now called the Al Ibrahimi Mosque.

On February 25, 1994, radical settler Baruch Goldstein went to the mosque with a hand grenade and a machine gun and opened fire on the people praying there.

He killed thirty Palestinians, and about 270 were injured.

Afterwards, the mosque was closed down for half a year by the Israelis, and when it was opened again for worship, half of it had been turned into a synagogue.

The Palestinians say that the Jews have bought their synagogue with Palestinian blood.

One friend of ours told us about his memories from the time of the massacre, when he was only ten years old and three of his friends from school were killed.

One friend of ours told us about his memories from the time of the massacre, when he was only ten years old and three of his friends from school were killed.

He himself had been praying with his father in another mosque that day. The next day when he went to school, he saw that the teacher had put flowers on the desks of the dead children, and our friend told us that he was so sad about losing his friends that he didn't want to go to school anymore and look at the empty seats. So his parents had him transferred to another school.

While Jerusalem seems normal if you don't look too closely, no normal life is possible for Palestinians in Al Khalil, the Arabic name for the West Bank town of Hebron.

[youtube=

166,000 Palestinians live here. But a big part of the inner city is closed to all Palestinian cars, supposedly for the security of just 700 Israeli settlers (officially they are 700; Palestinians say they have counted no more than 400 settlers in Hebron at any one time. There is, however, a larger totally fenced-in settler colony, Kyriat Arba, right next to Hebron).

Those settlers are protected by eighteen hundred Israeli soldiers.

In the closed-off section of Hebron, Palestinians above the age of 16 are not even allowed to ride a bike. When they are lucky, they may push a small two-wheeled cart to transport heavy items. But often, not even those carts are allowed to go through the checkpoints.

Usually people have to carry everything they buy from outside up the hills, including the supplies for the small shoe manufactories, as well as the finished shoes. The hills in Hebron are very steep. Once I saw three teenagers carrying a new, still packed-in washing machine up through the dirt paths of the olive groves. I saw their mother waiting for them outside the house.

On school days you can see three other teenagers pushing their handicapped brother or friend up the steep hill. They seem to be used to it. But still, half-way up the hill, they have to stop and catch their breath.

Well, I had to catch my breath walking up those hills even without carrying anything.

There is one donkey which is allowed to pass next to the check-point. It is owned by the milk-man. Every day it carries heavy milk bottles and other supplies up the hill.

There is one donkey which is allowed to pass next to the check-point. It is owned by the milk-man. Every day it carries heavy milk bottles and other supplies up the hill.

One of the things people have to carry regularly uphill are the heavy iron gas-bottles, which they connect to their gas stoves to cook their meals, since there are no gas-lines in Hebron.

Occasionally the people have to carry the sick and injured down, since it often takes far too long a time to wait for the Palestinian ambulance to get permission to pass the check-point.

A friend told us that when his wife went into labor and he wanted to get her to the hospital, he waited for two hours for the ambulance to get permission, and it never came. In the end, he had to carry her in his arms through the olive groves in the middle of the night, although there is no light. (I went through the olive groves at night and it really is dark there). He couldn't walk down the road, since his house is located right next to a settlers´ compound and an army station, so if he had passed there at night without permission, they would have shot him.

I know that place, and I know he was not exaggerating; they are very trigger-happy at that spot. I also watched his wife pass by on the road while carrying her baby, and they were throwing stones at mother and child.

Of course the olive-groves aren't all that safe either, not even in broad daylight. The settler youngsters gather there in groups and ambush any Palestinians working their lands or tending their sheep with a hail of stones. The same happens to Internationals who dare to walk there alone.

Of course the olive-groves aren't all that safe either, not even in broad daylight. The settler youngsters gather there in groups and ambush any Palestinians working their lands or tending their sheep with a hail of stones. The same happens to Internationals who dare to walk there alone.

At the checkpoints, which lead out of the Israeli-controlled area, Palestinians and Internationals have to walk through metal detectors and all bags get checked.

At the smaller checkpoints inside the area--and there are many of these extra check-points--bags are often checked again.

And they also do body-searches there, right in the middle of the street.

And they also do body-searches there, right in the middle of the street.

Palestinian men most often have to lift up their shirts, their undershirts, and their trouser-shafts, and then they have to turn around in a circle. Sometimes even young boys are treated like this.

Women are normally checked with metal detectors; children too, even the tiny first graders going to school.

Sometimes, if the Palestinians are lucky, their bags are checked with those metal detectors as well. But when they are not so lucky and they carry big bags filled with shopping, they often have to empty them right on the street.

Nearly everybody complies quietly.

When anybody protests, he is detained, which means his ID card is taken and checked and phoned in to military command.

And then the person has to wait thirty to sixty minutes, or even longer, until the soldiers get a clearance call from their superiors confirming that the detained person isn't wanted for some violation. If a Palestinian protests too much, the police are called and he is taken to the station, where he will be detained for several hours, and will nearly always have to pay a fine before being released.

But more often than not, Palestinians, especially young men, are detained for no reason at all, other than for walking on the street.

Few dare to protest, for if a Palestinian is picked up by the military police, he will be brought to the base and tortured. Torture means he is beaten up and sometimes worse.

Most often the Palestinian is chained in an uncomfortable position for many hours or even days, until every muscle in his body aches. He will not be allowed to sleep, being kept awake with blaring loud music or screeching noises.

He will have a bag put over his head, normally one smeared with feces, so people nearly faint from the stench.

Several of my Palestinian friends went through this kind of torture before being permanently jailed for years. One of my friends told me that there was one blessing from all this--before he went to jail, he knew nothing, but in prison he became educated.

The Palestinians in the prison where he was sent were well-organized. They had hunger-striked themselves into being allowed to have books and chairs and tables. For everything they wanted, the prisoners needed to organize a hunger-strike, my friend told me. And then the leaders of the inmates would tell all the prisoners they had to read three books every week, one for politics, one for religion, and one novel.

Then the older Palestinian man looked at his younger friend and said: "But nowadays things have changed, the prison in your time isn't as good anymore."

The young Palestinian said: "But still even today all the good people are in prison."

He turned to me: "You know, in all other countries in the world all the worst people are in prison. Not here--in Palestine, it's always the best ones."

Hebron's Shuhada street used to be one of the richest shopping streets in all of Palestine; now all the shops have been closed down.

Hebron's Shuhada street used to be one of the richest shopping streets in all of Palestine; now all the shops have been closed down.

For three years, the area was put under total curfew--no one was allowed to walk the streets. People had to take to the roofs when they wanted to get out of the house to get food or go to work or even to go to school.

The three families who lived between the 2 Israeli settlements there had had their front-doors welded shut.

Palestinian families who live in the other part of the street are still not allowed to walk past the settlements or to visit those houses in between; the inhabitants of houses above Shuhada street and the children who attend the school there have to use staircases and roundabout pathways because they are forbidden to walk the streets which pass the settlements.

But even while following all the rules set by the occupation authorities, Palestinians are still not left in peace.

They are constantly harassed by settlers, even on the streets or paths on which Palestinians are allowed to walk.

Harassing Palestinian women and children seems to be some kind of settler sport, really. They laugh while doing it; they think it’s fun.

Often, however, these attacks are systematic. They are being done to empty the Palestinian houses of their occupants, to terrorize them into leaving so that the settlers can enlarge their territory. Some settlers have actually admitted to this tactic on camera, while they assumed the reporter conducting the interview was an American Jew sympathetic to their cause:

[youtube=

The Israeli soldiers stationed at those different checkpoints all over the old city practically never intervene on behalf of the Palestinians.

Once I asked a soldier why he wouldn't intervene, and he told me that this wasn't his job; he was there to protect the Jews.

But if a Palestinian ever pushes back, even a child, he or she will be arrested.

This situation is the reason why international human right workers watch the streets or patrol the pathways or the olive groves. Hopefully, by just being there, they might prevent harassment and attacks by the settlers against the Palestinians.

And if necessary, internationals will intervene by non-violent means. Internationals also try to monitor the soldiers' behavior towards the Palestinians. At checkpoints, where there is no international presence, or in Gaza where internationals often can't even get inside, human rights abuses are usually far worse.

Yes, it's true, internationals act as human shields.

You think it's crazy, a martyr's complex or something like that?

Think what you will.

But I know it's logic, it's the only way possible.

Here are a people without rights, none at all: the Palestinians. And here are the internationals, people who still have rights protected by their embassies and their countries back home. So as an international spreading your arms to help a Palestinian woman and her baby escape to safety beneath a hail of stones, you assume that the settlers will stop, for otherwise, they will get in trouble. You trust in that and stand your ground.

But there are times when they don't stop--not the settlers, not the soldiers, nor other representatives of the state of Israel.

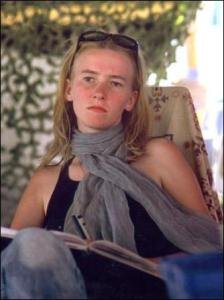

Rachel Corrie, the young American girl who was killed, had faced a bulldozer driver. The people from ISM who knew about the event have told me that Rachel had looked straight into driver's eyes.

Rachel Corrie, the young American girl who was killed, had faced a bulldozer driver. The people from ISM who knew about the event have told me that Rachel had looked straight into driver's eyes.

She must have been sure that he would stop. She had trusted in his humanity. And when she realized he wouldn't stop, it was too late, she could no longer escape.

Sometimes they just don't stop….

Most internationals will be attacked at some point, if they stay long enough. A friend was once thrown down the garden stairs in the olive groves. Another time, he was beaten up by soldiers. He told us newcomers during our introduction to the area that if we needed to be stitched up or fixed otherwise, we should go to a Palestinian hospital, since they do the "stitching up" for free.

(I only needed one such hospital visit.)

I was physically attacked twice, although I was really not too badly hurt either time.

The second time, settler teenagers had led us into a trap in order to grab or destroy our camera. They had just attacked several Palestinians and when we interfered by calling out and running towards them, thus giving the Palestinians a chance to escape, the settlers saw the camera and thought we had it all on tape.

The camera was our only weapon. Unless we got the attacks on camera, Israeli authorities would deny everything. The settlers are not given any limits or boundaries regarding what they can do to the Palestinians.

The camera was our only weapon. Unless we got the attacks on camera, Israeli authorities would deny everything. The settlers are not given any limits or boundaries regarding what they can do to the Palestinians.

The ISM companion I was with at the time was attacked from behind, hit over the head with a stone, and then relentlessly beaten and kicked. I screamed as loud as I could, and tried to grab one of the attackers to pull him off. And then my mind must have blacked out, for I don't even remember how I got those bruises, nor do I remember the faces of our attackers very clearly.

This of course made me a lousy witness when we filed our usual and utterly useless charges at the Israeli police station.

The only thing the police did was blame us for the attacks, telling us we had provoked the settlers.

Shaken up as I was, I nearly fell for this mind-game the police were playing on us. So when I phoned in the attack to ISM´s headquarters in Ramallah, while my companion was still lying in hospital with a concussion, I thought I had to convince even our own people that we, my companion and I "had really, really, really not provoked the settlers", nor started filming before the attacks, and so on.

Only a few days later, the same companion was singled out by Israeli military police when we attended a demonstration outside Hebron where once again, Israel was confiscating Palestinian farmland and uprooting fruit-trees to expand Jewish settlements.

My companion was sitting down with a group of protesters to block the path of the bulldozers when the MPs grabbed him by his feet and dragged him dozens of meters along the gravel road before finally allowing him to get up. Then they proceeded to cuff and arrest him.

He wasn't deported but he was banned from the Hebron area.

Of course we hadn't provoked the settler violence. There had been far more violence before internationals had come to Hebron. And in places where there are no Internationals or Israeli human rights activists, the soldiers have no limits on their actions either.

The ex-soldiers who had been stationed in Gaza admitted in an interview with Israeli psychologist Nofer Ishai-Karen (herself an ex-soldier in a Gaza occupation unit) to having trampled on tiny children and kicked pregnant women in the belly. They had also tortured prisoners they had had to transport, and so on.

Similar things as those described in Ms. Ishai-Karen´s research also occurred in Hebron at the beginning of the second Intifada.

People from the "Palestinian-Authority" side of Hebron have told me about a certain "hat-drawing" ritual:

A certain military police unit would go through the streets of Hebron during curfew hours, and they would capture everyone they found outside, and make them draw a piece of paper out of some helmet or cap.

Whatever was written on this piece of paper was then done to the unlucky Palestinian who had been captured.

Inscriptions on those papers were:

have an arm broken,

have a finger broken,

have a leg broken,

be thrown from a moving army vehicle,

or receive a bullet in the leg.

The man who told me this said he had known a young teenager who been killed by being thrown from a moving vehicle.

A man he knew got a bullet in the leg this way and was then told to crawl to the end of the street while the soldiers counted to fifty. If he didn't make it, he would then get a bullet in the head.

The terrified man crawled and crawled while he heard the MPs counting, but he didn't make it in time to the end of street.

But he wasn't shot in the head.

They just drove away laughing.

This "hat-drawing" practice only stopped when the resistance started to especially target this sadistic MP unit.

Nowadays in "relatively calm" times, the worst incidences in Hebron normally happen on Saturdays, the settlers’ Sabbath, as well as on religious holidays.

On those days, the settlers choose not to drive their cars for religious reasons.

Instead they walk, like the Palestinians have to all week long.

The settlers usually walk around in large groups, harassing every Palestinian on their way.

On holidays, the settlers celebrate, and sometimes they close their celebrations with mass-attacks on Palestinian houses.

So on those nights, internationals stay with the Palestinian families who have been attacked before.

One holiday night, a young English woman and I stayed with a family whose house is regularly attacked after these celebrations. This time, the settlers had collected lots and lots of wood for a very large campfire in the middle of the olive-groves, right in front of one of the houses which the settlers had emptied by terrorizing the Palestinian owners and later demolishing everything inside and writing obscenities on the walls.

They turned up their loud-speakers so high that surely their speeches were heard over half of Hebron. In between, we could hear some hooray shouts from the whole group, which was composed primarily of young men and male teenagers. Because we couldn't sleep, we watched the event from afar, together with some members of the Palestinian family with whom we were staying.

At the time, the whole experience gave me an eerie feeling of unreality, as if we were in a movie portraying Nazi-times. There we were, crouching behind the stone fence of the family's garden, together with their teenage daughter, listening to loud fanatical speeches, and then we saw the settler youths dancing around the fire, singing and shouting.

And eventually we watched them raise a long pole with some cloth on it. They held it over the fire and when it lit up, the Palestinian girl next to me gasped, for she had recognized it. The settlers were ceremonially burning a Palestinian flag. It was just creepy.

We stayed awake the rest of the night. The year before, a flag hadn't been the only thing the settlers had tried to burn on this particular holiday. A woman in the next house had been terrorized so badly by "celebrating" settlers that she had had a miscarriage.

When the settlers found out I was German, things got a bit nasty for me as well. I was threatened and accused of being responsible for all those 6 million who had died in the Holocaust. I thought this wasn't fair, since my mom had had a lousy childhood under Nazi rule. So I told those accusers about my mother's Jewish background.

Things got even crazier from there.

The soldiers started to make fun of me.

The soldiers started to make fun of me.

One day the soldiers closed one of the checkpoints for Palestinians--for technical reasons, they said. Of course, they could have used their hand-held metal detectors, and let the people pass by around it, if they had wanted to.

And we Internationals asked the soldiers to do so. But soldiers weren't going to make it easy for Palestinians. That wasn't their job.

They let the people wait in line endlessly just to make things a bit more miserable for them. Then I got in line to wait for the next time they would let people through, to go to a shop on the other side.

The commanding officer, however, told me in front of the whole line of waiting people, that I wouldn't have to wait--after all, I was Jewish.

I told the soldiers that I was a human being like everyone else and I would wait.

The officer, by the way, was a British man of Jewish descent, who seemed to have joined the Israeli army just to get in on the fun of harassing Palestinians.

While some settlers still kept threatening to hasten my demise, the leader of the settler community in Hebron told me that while I might be Jewish according to his law, my German side seemed to be stronger than my Jewish side.

While some settlers still kept threatening to hasten my demise, the leader of the settler community in Hebron told me that while I might be Jewish according to his law, my German side seemed to be stronger than my Jewish side.

This man, by the way, had been a good friend of the late Baruch Goldstein, I mentioned earlier, who had massacred 3o Palestinians at the Al Ibrahimi mosque.

One Saturday when this settler boss was leading a large group of Jewish American visitors through the area as was his custom, he pointed me out to them as they passed by, saying in a loud voice:

"Look at her. Her mother is Jewish and her father a Nazi, and she is here to continue her father's evil works."

Another settler, the compound’s bus-driver, tried to save my Jewish soul. But he first absolutely insisted on my telling him exactly how many Jewish grandparents I really had. I guess he needed to make sure my soul was truly worth saving. He told my international friend, standing next to me during one of those soul-saving attempts, to shut up. He wasn't going to talk to her, he declared, since in his book, I was worth a thousand times more than the likes of her.

Another settler, the compound’s bus-driver, tried to save my Jewish soul. But he first absolutely insisted on my telling him exactly how many Jewish grandparents I really had. I guess he needed to make sure my soul was truly worth saving. He told my international friend, standing next to me during one of those soul-saving attempts, to shut up. He wasn't going to talk to her, he declared, since in his book, I was worth a thousand times more than the likes of her.

Guess how that "compliment" made me feel.

But the bus-driver's soul-saving attempt didn't interfere with his other "settler-duties", which primarily consisted of making Palestinians´ lives miserable.

When one of the bus-driver's daughters claimed that she and a few other little girls had been attacked by two Palestinian teenage boys, he insisted on having those boys arrested.

We had walked up the hill all the way with those boys and we knew the little girls had been far ahead of us. The boys hadn't even been close to them. They had proudly practiced their English with us, showing us how well they had learned in school.

And then the soldiers detained them.

"Please," I tried to reason with my would-be-soul-saver, "those boys are innocent. We were there, we've seen it. You know me, I would never allow anyone to hurt a child, not your children either."

But he just smiled, said his daughter wouldn't lie, and then told me that one day I would have to meet my maker, taking responsibility for what I was doing there, helping "the enemy".

And then he had the boys arrested.

It was so frustrating for me to see those innocent boys being taken away. It was a feeling of utter helplessness, knowing whatever you say as a witness, it does not count with either the soldiers or the police.

The boys were released the next day, but naturally, not until their families had paid their bail.

But one shouldn't call it bail, really. It's more like a ransom.

Palestinians, often teenage kids, get arrested all the time, mostly for no reason at all. The parents are then asked to pay bail, if they want their children returned to them. When the charges are dropped, the "bail" is then called a "fine" and never returned. I guess Israel needs a bit of extra-financing. The occupation is expensive after all. For most Palestinians, the "bail" is a lot of money for families who are very poor.

I once saw a rural Palestinian woman ransoming her teenage son. She wore the old traditional Palestinian dress. She had some teeth missing from her mouth. While waiting outside the gate of the police-station, she held some bills in her hand, waving them at the camera over our head whenever she heard a crackle in the broken-down loud-speaker. She wanted to show whoever was watching that she had got the money to get her son out of jail. This rural woman clearly was no person with money to spare. Three little girls were holding on to her, looking scared, while we waited for hours in the hot sun in front of the gate of the Israeli police station.

We internationals were there to file another useless complaint about an attack on us. It seemed to be such a waste of time. But our Palestinian organizers thought it would be good to make the reports, just for the record.

Many other Palestinians were waiting as well; waiting in line for endless hours in front of check-points or gates is the normal routine for Palestinians.

Many other Palestinians were waiting as well; waiting in line for endless hours in front of check-points or gates is the normal routine for Palestinians.

The other Palestinians waiting in front of the police station gate had to get a permit for something or other--Palestinians need permits from the Israeli police for lots of things.

After some three hours, we heard a crackle in the speakers and most Palestinians went away. I guess it meant there would be no permits given out that day.

But we eventually got in to make our complaint, and the woman finally was allowed to "bail out" her son.

When we left, we saw the peasant woman and her teenage son leaving as well, the three little children in tow.

Despite all these every-day humiliations, the Palestinians shrug and take it. That's just life in Palestine for Palestinians. Everyone knows it, so you adjust.

.

A Family's nightmare

But then there are those things you won't recover from.

Outside the closed off zone is the area which is supposedly under the control of the "Palestinian Authority". To call it that is no more than a big joke. The "Palestinian Authority" has authority over the traffic and the streetlights and that's about it.

The Israeli army can enter the area whenever they want, enter any house, arrest anyone and hold him for as long as they see fit, without warrant, without trial, without rights.

The Israeli army can enter the area whenever they want, enter any house, arrest anyone and hold him for as long as they see fit, without warrant, without trial, without rights.

And arresting people is what they do on a nightly basis. And while they are at it, they sometimes shoot.

One of those "incidents" occurred during my time in Hebron.

The soldiers wanted to arrest somebody late at night. They banged on the door of a house. When a boy opened, they started to beat him up, and when his sister tried to help him, they hit her too. This was too much for the father of the family, an elderly man of 63. He interfered with his bare hands and so was shot in the throat. When his wife in desperation tried to pull off the soldiers from her husband, she too was shot, in the head. Then the soldiers started to beat up everyone else in the family, for now the family was frantic with despair.

Two sons tried to get their mother into a car to drive her to the hospital for she was still alive. But the soldiers confiscated the car keys and wouldn't permit the Palestinian ambulance to pass. Why? The woman wasn't thought to live, I guess. And sometimes, when Israeli soldiers shoot Palestinians, their military doctors remove the bullets, so the army can claim the victim had been hit by a stone, thrown by Palestinians themselves.

But this woman survived. Eventually she got to the hospital, but by that time, she was diagnosed as nearly brain-dead.

In the end it wasn't even quite clear if the soldiers had actually barged into the right house. Was it actually a neighbor they had intended to arrest?

The next day, the name of one of the sons was released as the soldiers´ supposed target. He went to the Israeli police-station. He told the officers there that he would have come quietly. Why did they have to do this to his family, his parents, why? The police just sent him home.

Its possible the soldiers didn't plan to shoot those people when they rammed into the house--it is the occupation which leads to these escalations of violence in nervous or trigger-happy young soldiers. When Palestinians have no sanctity of their homes, when Israeli soldiers can barge in any time and can use whatever force they want on the people inside, then these killings happen over and over again.

I wasn't there, but one of our Palestinian organizers knew the family. He went to the house and talked to the family. He came back and told us what had happened.

He told us the house looked like a slaughterhouse. Blood everywhere, from ceiling to floor and on all the walls. He also told us what the family had been doing right before their world collapsed. They had been planning the wedding of one of the sons and they had just been looking at the invitation cards, which had come fresh from the printers.

This detail of the story hit our friend hard. He is a young man who was himself in the process of planning his own wedding which was to be the very next month.

.

The Other Side of Palestine

But while watching all this misery and nearly unbearable injustice, I also got to know the other side of Palestine.

There were the days and nights we spent with Palestinian families, when trouble was expected. We would try to communicate, try to learn Arabic.

There were the days and nights we spent with Palestinian families, when trouble was expected. We would try to communicate, try to learn Arabic.

They taught us and laughed at us, at how funny we sounded.

Most communication though was still by hand and foot, which was a lot of fun as well.

The people opened up their family albums for us, and we showed them pictures from back home. And they always offered us delicious food to eat, much better than the food we made in our humble kitchen at the place in which we lived.

Occasionally I even would do a bit of real honest-to-goodness labor. Like here, when some other internationals and I helped a Palestinian farmer’s family to harvest their fields. In this case, we helped the family to cut feed for their goats from their field. Previously, every time the family tried to bring their goats into the field or to cut it themselves, they had been attacked by settlers. The settlers were intent on taking over the family's land in order to cut a pathway connecting two settlements while cutting off the Palestinians.

Occasionally I even would do a bit of real honest-to-goodness labor. Like here, when some other internationals and I helped a Palestinian farmer’s family to harvest their fields. In this case, we helped the family to cut feed for their goats from their field. Previously, every time the family tried to bring their goats into the field or to cut it themselves, they had been attacked by settlers. The settlers were intent on taking over the family's land in order to cut a pathway connecting two settlements while cutting off the Palestinians.

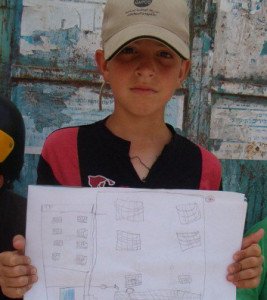

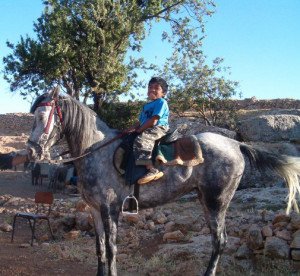

Here are two of the family's children:

Then there was the day when a companion and I were attacked and pressed against a railing by a whole group of Israeli settler kids.

They kept on kicking us and there was no way out--we couldn't even turn around and try to climb over the railing.

An Israeli soldier came running down the stairs from his post over the street. He told those settler kids to stop, but they didn't. He pressed himself through the group and placed himself between them and us.

They still kicked around him, might even have hit him too. But now it was relatively safe for us until finally the police arrived, and the kids ran away.

When I saw the soldier again, I thanked him. He just nodded and waved me off--he didn't want to talk about it.

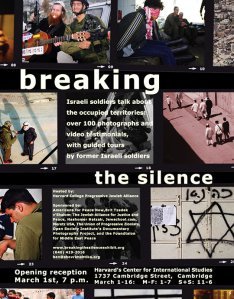

Every Saturday we met an ex-Israeli soldier, from the "Breaking the Silence" movement, on the street. He had once been stationed in Hebron. He was leading a group of Israelis or Americans around, explaining to them what the occupation did to the people of Hebron. And those who went on his tours may have had their eyes opened to the facts, possibly for the very first time.

Every Saturday we met an ex-Israeli soldier, from the "Breaking the Silence" movement, on the street. He had once been stationed in Hebron. He was leading a group of Israelis or Americans around, explaining to them what the occupation did to the people of Hebron. And those who went on his tours may have had their eyes opened to the facts, possibly for the very first time.

(The settlers have their own tours, actually at about the same time and through the very same neighborhood, and yet their visitors see different things. Eyes aren't the only thing you need, if you really want to see….)

There was the time when the Israeli human rights workers came and joined our Palestinian friends and us. And we felt there was no difference between us all.

Deep friendship had developed between the Palestinians and those Israelis.

One evening we went together to a coffeehouse. The Israeli was a bit nervous to join us, since the coffeehouse was outside the closed zone of Hebron in the area of the "Palestinian Authority".

But one of the Palestinians put his arm around his shoulders and told him: "Don't be afraid! Nobody would ever harm you out there, you belong to us."

There was the demonstration we went to, which Israeli peace activists attended. When the soldiers started to arrest people, they also tried to grab a couple of Israelis, and the Palestinians did what they always do when somebody is being grabbed by the soldiers--they tried to pull them out, and they succeeded.

If a Palestinian is arrested, he might be thrown in jail for years; an international will only be deported back home, and an Israeli stays in jail for only one or two days. And yet, when the Israelis demonstrate on the Palestinian side, they become some of them and the Palestinians would fight for them, just like they would for their own demonstrators, no matter the cost to themselves if the soldiers decided to grab them instead.

A people who are on moral high ground can be generous in spite of whatever has been done to them before.

The "never forget - never forgive" is not a Palestinian attitude.

Then there was the time when our whole group was invited to a birthday party at a Palestinian home. One of our friends led the way, and as usual, everybody had to wait for me to make it uphill.

Our Palestinian friend smiled and joked a bit.

"One day," I told him, "you will be old, too."

"You aren't old," he said.

And after a while, he added: "I feel like a hundred years old sometimes."

Now finally I found the courage to ask the question which had been on my mind for quite a while: "But why then, are you still so..."

I grabbled for the word, " so happy?"

It was the wrong word. But he understood, and he knew I didn't only mean him.

"We have to," he said, "we have to go on living."

Here he was, a wise man of only 22, in that year when I was in Palestine.

The birthday party actually was a surprise fare-well party for me, complete with a nice cake. We stayed inside and had a good time with the family.

But the very same day, only a few hours earlier, the family had been sitting in their garden having tea with their visiting relatives when an avalanche of stones came down on them. They showed those stones to us, and some of them had been really big. The family had actually been quite lucky that nobody had gotten seriously hurt.

The stones had come from the army base next door.

The family’s father went and complained to the army commander. The commander just said "It wasn't us.” "But it came from the base," our friend insisted. "No," the commander said, "soldiers don't do this. It must have been settlers. But since you didn't see which one of the settlers did it, we can't help you."

So our friend went back home, shrugged it off, and he and his family prepared the party for me and the other internationals.

.

The Child and the Bullet

But most vividly I remember the children, who played around us and with us while we were watching the checkpoints. Like all children everywhere, they lived for the moment. They made us laugh and occasionally even made us forget the grim reality around us.

The boy in the picture above is Mohammed. He is Moussa's friend and an up-and-coming Palestinian artist. In 2007 he was 9 years old.

The boy in the picture above is Mohammed. He is Moussa's friend and an up-and-coming Palestinian artist. In 2007 he was 9 years old.

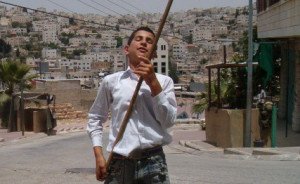

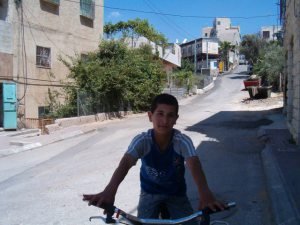

And then there was Moussa

Moussa himself was 11 years old the year I was in his town Al Khalil (Hebron). In the picture to the left he is practicing some acrobatics for the street circus some internationals occasionally organize for the children of the area. In the background is the street-check-point with the soldiers in the shadow. The name Moussa b.t.w. is Arabic for Moses.

Moussa himself was 11 years old the year I was in his town Al Khalil (Hebron). In the picture to the left he is practicing some acrobatics for the street circus some internationals occasionally organize for the children of the area. In the background is the street-check-point with the soldiers in the shadow. The name Moussa b.t.w. is Arabic for Moses.

Moussa nearly always had this broad mischievous smile on his face. Most days after school, he helped his parents in their shop. But whenever he was free, he would ride his little old bike, which was held together mainly by duct-tape, and which lost its chain about once a day. The bike was actually getting a bit small for him and its brakes were Moussa's feet on the street.

But these were only minor obstacles, for Moussa rode it like a racing bike, hairpin turns and all. And sometimes he did acrobatics for us, the fawning international audience.

If you look at Moussa's broad smile, you would never guess all the things he had seen and heard so far in his short life.

Moussa lived through the second Intifada and later, the siege on Hebron, when the soldiers had positioned themselves on the rooftops of all the buildings on the highest hills, including the rooftop of his parents house, and from there, they had shot at everything that moved.

He had seen the time when there were endless curfews, often lasting for weeks at a time. During those curfews, people couldn't even go out shopping or visit their relatives and neighbors.

Some of Moussa's relatives had been arrested and sent to jail during that time.

The year before, Moussa had been attacked by settlers. His friend Mohammed had drawn a picture about it. He showed it to me:

You could clearly see the house of Mohammed's family, with the two security cameras the soldiers had attached to the roof.

You could clearly see the house of Mohammed's family, with the two security cameras the soldiers had attached to the roof.

And you could see a scared little face looking out of a barred window; (probably little Mohammed himself)

And in front were soldiers and Israeli military police with their armored car and the "mustoudinin", the settlers. And the stones were in the air, flying - and Mohammed told me that the two little figures on the bottom of the drawing, first the one on the bike with a big stone heading in his direction, and then, the one lying bleeding on the ground and unconscious, were both Moussa.

Sometimes the soldiers are nice to Moussa and to the other kids, and sometimes they aren't.

Once they told Moussa that if he wouldn't do what they wanted, they would take him up to the top of the hill to their base. Moussa knows that people get tortured in that army base; everyone knows.

One day when we arrived at the street checkpoint, we saw a man who had been detained. We hadn't seen what had happened before he had been detained and we could't communicate with him. He spoke no English.

Moussa came along and we asked him to translate for us. Moussa talked to the man and then, with hands and feet, Moussa explained that soldiers had told the man to drop his trousers in the middle of the street and the man had refused.

The soldiers then called the military police. And the man was arrested for disobedience and hauled off to the army base. But we internationals took pictures of the arrest, to prove that he was without any wounds or anything before they transported him up there. The man was then released the next day. His sister called and thanked us for having been there. She said that her brother was fine.

And then there was the day when Moussa found a machine-gun bullet on the street.

He was riding his bike as usual. Suddenly I saw him stop, stoop, and pick up something from the ground. He got back on his bike, riding towards me to show me what he had found.

He stopped in front of me, where I was watching the checkpoint.

It was a bullet as long as the child's hand and it had a vicious looking odd. The bullet must have dropped from an ammunition belt.

Nervously I looked over Moussa's shoulder, not knowing what to say to him without the soldiers noticing.

The soldiers hadn't seen anything, they had turned their backs to us and were talking together.

"Bad" said Moussa looking at the bullet in his outstretched hand, "bad."

Moussa closed his hand tightly over the bullet, drove another round on his bike, then turned and rode over to the soldiers, stopping with his feet in front of them.

And then he handed the bullet over to one of the soldiers.

He got back on his bike and rode back to me, and with his broad typical Moussa smile he said:

"Moussa not bad!"

No, my little Moses, you are not bad, not bad at all!

Thank you so much for your donation to Independent Journalist Tom Duggan! Much love and respect @evehuman! xo

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

The only reason for time is so that everything doesn't happen at once.

- Albert Einstein

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

ok, old man, and what does that have to do with the subject at hand?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Upvoted and Resteemed. Thank you for the donation by the way. I'll be using some of it to get this post resteemed to a larger audience using @steemvote

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

thank you, I appreciate that

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Resteemed by @steemvote

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

thank you

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you so much for this detailed report, and for documenting all you know, and everything you saw while you were in Palestine. I hope many read this!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you for reading it yourself. Since the article won't make it to the trending page, very few people will get to see it.

But then, it's already a 10 year old story.

You go on and present new reports and get people's attention so that more and more will learn the truth of what is happening right now in Palestine.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I have shared this, and part 1 in many groups, so hopefully some people will read it and gain awareness from your experiences!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

thank you so much

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Awww, thank you SO much you sweet Angel, I just saw what you have done!! I feel so happy and excited. You are an amazing human, and a Super Woman. Please accept my compliment and my gratitude <3 <3 <3 XOXOXOOXOXOX <3 <3 <3

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

really it was nothing, I'm just so glad, that there are young people like you who work for justice and peace, in Palestine and in the world.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I'm so glad I met you and I look forward to spreading truth together, here on the blockchain. It feels so good to share reality with you! Not too many know about Palestine. And even fewer know the truth. Most just listen to what their TV says...I appreciate YOU.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @evehuman! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Eve you beautiful human you, Tom sent you a message. https://steemit.com/hendrix22lovesyou/@deliberator/tom-duggans-thank-you-to-steemit-lyndsaybowes-evehuman-everybody

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit