The USSR Constitution of 1977 said

Article 19. The social basis of the USSR is the unbreakable alliance of the workers, peasants, and intelligentsia.

The state helps enhance the social homogeneity of society, namely the elimination of class differences and of the essential distinctions between town and country and between mental and physical labour, and the all-round development and drawing together of all the nations and nationalities of the USSR.

A possible defence of the Soviet Union is to appeal to equality and basic needs. Even if one has accepted that the system was worse performing than the market economies of the West, one could still argue that what really matters is to cover basic needs first. What use, could one say, is having an economy that allows the existence of super-rich people and supermarkets that sell five different kinds of hummus when there are other people that are destitute?

Our analysis begins with an article published in 1977 by Alastair McAuley, The Distribution of Earnings and Incomes in the Soviet Union. The reason being no other that this article is one of the first ones. The data he uses in his article comes from official Soviet sources, with a peculiar catch: the government itself doesn't publish the income distribution statistics directly, but they do publish several data items that can be used to put it together. McAuley discusses the advantages and weaknesses of these datasets (Family budget surveys, income surveys, earnings censuses, and earnings surveys). Some findings of his were that inequality (Measured by the decile ratio) decreased by around 40% in the 1956-65 period, achieved by a faster increase of the earnings of the poor (144%) compared to those of the richer citizens (38%). The authors point out, though, that if looked from the point of view of how many more rubles they are making, the gains in absolute terms are equal for all groups. By 1967-68, the decile ratio was around 3, meaning that the richest citizens, on average, were earning three times as much as the poorest ones, which seems quite equal. In comparison, the UK had a ratio of 3.4.

The article also provides an estimate of how many families were in a situation of poverty, as defined by the fact that in 1974 the government introduced a subsidy for needy families that earned under 50 rubles per month. This, together with the fact that inflation rates are low, allows McAuley to retroactively calculate poverty rates in 1967, for he has data for that year. And that amount is staggering: In the best estimate, including state farm workers, around 40% of the entire population in 1967 would be considered as poor by the Soviet standards of 1974.

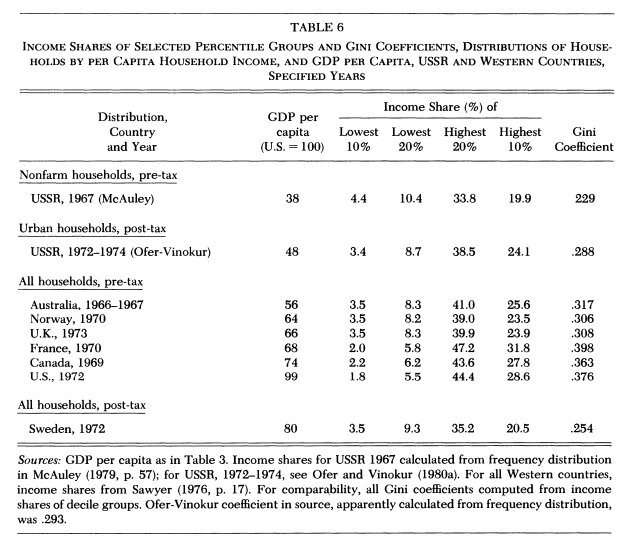

The next paper of relevance is the clearly named Income Inequality under Soviet socialism by Abram Bergson (1984). Like McAuley, he spends quite a few dozen pages discussing methodological issues and the tricks one has to go through in order to provide a reasonable estimate of the income distribution in the USSR. IN the paper he cites two Gini coefficients, using different data, methods, and different years. One is an estimate calculated from McCauley's data and the other from Ofer-Vinokur's papers that he references. According to Bergson, McAuley's data underestimates inequality, and Ofer-Vinokur overestate it, although he thinks the latter are closer to the underlying truth. Both numbers are not that different, as you can see in the table below. In any case, they reinforce the idea that the Soviet Union had indeed low inequality, comparable to Nordic social-democracies of its time.

Regional inequality

So far we have seen an overview of inequality in the aggregate of the USSR. But the USSR is mostly Russia and Ukraine in terms of population. How does the data look like if we look at the individual constituent republics?

The Soviet Union not only tried to equalise incomes across the USSR, but also in theory, also between different republics. Ozornoy (1992) mentions that indeed that happened until the 1950s, but since then, little convergence has happened. This is in spite of economic growth, as the birthrates in the poorer republics outpaced it, increasing the denominator of per capita GDP. Ozornoy mentions that for most of its history, investment policy in the USSR was essentially centralised, and it paid little regard to the differences between republics, considering only the USSR as a whole.

The pattern of investment distribution among the union republics during the period 1976-88 does not reveal any systematic effort to use the allocation of investment as a policy tool for reducing development disparities, particularly when allowance is made for the differing rates of population growth. Rather, the pattern suggests that the federal government, while providing an increment in investment to ensure some development in all republics, based its spatial investment allocation decisions on an assortment of general economic and geographical considerations, such as resource and energy development in Asiatic RSFSR, rates of return on capital, accessibility to markets and geopolitical factors. The primacy of the ‘state as a whole’ considerations over equity considerations in the investment shifts may be seen as a perfectly logical approach by decision-makers within the federal administration which actually pronounced that the task of inter-republican equalization had been resolved!

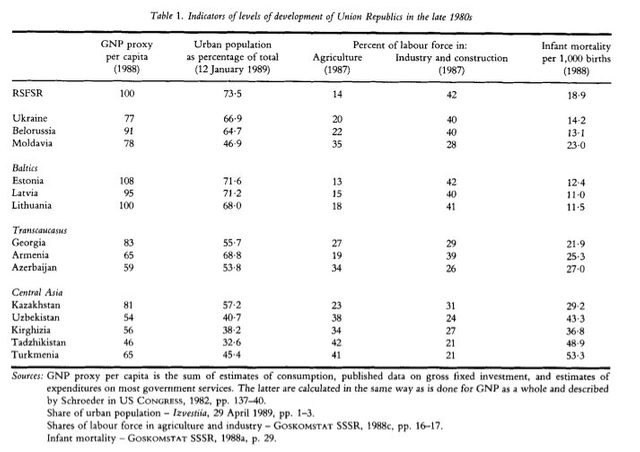

In the late 80s, this is how the UUSR looked liked decomposed by republics:

As you can see, this doesn't seem very equal, and to some extent it mirrors the economic development of the republics post-USSR. The richest republics were the Baltic's, and the Central Asian republics, the poorest. A view to salaries reveals the same picture, so our intuitive inference of average consumer income from per capita GDP is merited: