When I was a university student living in Europe as part of a study abroad program, my favorite places to visit were museums. They offered me a kind of solace. They were where I would go to get away from everything: the heavy course load I was carrying, the harried traffic of the city, the incessant noise and chatter, and the cold dreary winter weather which seemed to penetrate my very bones.

The Museo del Prado was such a place.

Each time I made my way through the grand entrance, I felt a sense of enchantment. I almost fancied my ankle-length coat was a long gown from a bygone era. I glanced up at the massive columns of the portico, and then stepped through the doors as though into a palace.

The building itself is a historic structure originally commissioned during the reign of Charles III in 1785. During the Peninsular War between Napoleon and the allied powers of Britain, Spain and Portugal, it was even used as a gunpowder-store and cavalry headquarters for the Napoleonic troops based in Madrid.

Everything about the Prado enchanted me. From the gleaming marble floors, to the soaring vaulted ceiling, to the endless white galleries and halls hung with beautiful masterpieces. Even the smell of the interior evoked another place and time, transporting me instantly to centuries past.

There were days where I could enter one of the rooms and have it all to myself, then sit quietly on a bench and contemplate what those larger-than-life paintings have seen. Often I would step up closer to gaze into the eyes of one of the subjects, only to have them stare right back at me. What were they thinking in the moment they were immortalized by the artist? What secrets did they keep?

Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas seems to beckon the onlooker to step inside the room depicted in the 10’5” by 9’1” painting. I could almost smell the carved heavy wood furniture, the woolen carpets, and the fragrance of lavender and jasmine drifting in from the windows which would certainly have been left open to clear away some of the odor of the turpentine and oil paints. Feelings of anticipation and excitement create a stir as the King and Queen prepare to enter the room and see Velazquez’s work for themselves.

Albrecht Dürer’s Self-portrait has a knowing look, almost daring the viewer to discern his thoughts.

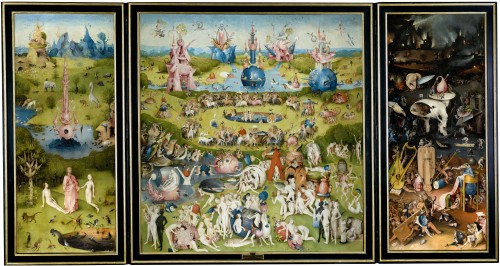

The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch is a fascinating biblical narrative in triptych form that is so detailed, one can visit the museum many times and still not take it all in.

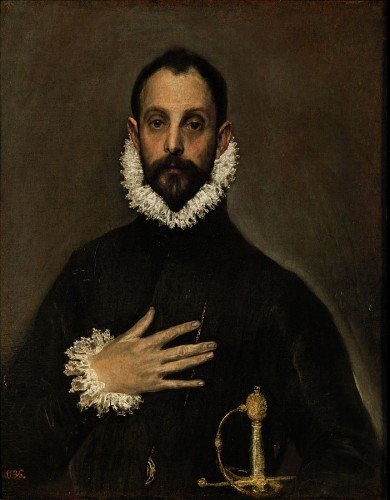

Then there is El Greco’s The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest. Something about the portrait is arresting and captivates the onlooker. Perhaps it is the feeling evident in the eyes of the lord. But then again, is it sincerity or lordly disdain? The way his right hand rests over his chest suggests a promise made, or a moment of revelation. His bearing is self-assured and dignified, down to the detail of his fine clothes, valuable sword, and the costly medallion peeking beneath his doublet. The slight lift of his brow is compelling and persuasive. The set of his mouth, decisive. Although the painting dates back to about 1580, it seems very much alive. Very real. I feel as though I could reach up and touch the texture of the nobleman’s face, and feel the bones of his slender fingers. His jaw would undoubtedly tense in surprise as I took the liberty of brushing the curve of his cheek. But then his hand would certainly close over mine in a firm grip once he regained his composure.

Such are the thoughts of a writer’s imagination. For the Prado is a place of secrets, revelations, and never-ending tales. A place where beauty has been immortalized, and emotions have been preserved in all their agony or delight, pleasure or pain. A place where the human condition is captured and displayed in all its existential truth.

In addition to exquisite works by masters such as Diego Velázquez, Hieronymus Bosch, Peter Paul Rubens, Titian, Raphael, Rembrandt, El Greco, and Francisco de Goya, the Prado’s vast collection includes thousands of paintings, drawings, prints, artifacts and sculptures. It is a veritable palace; a feast for the senses, and a banquet for the soul. There is a kind of sacred splendor about the place that is worth a thousand visits. A place to think and feel and dream. A place that offered me solace from the poignant longing and loneliness which were my close companions while living so far away from home.

The Prado’s graceful galleries and timeless masterpieces beckon with the promise of enchantment. It is worth getting swept away into another time, even if only for the duration of one’s visit. It will always be a special place to me. I’m sure this is due in part to my intensely romantic nature, which has only deepened with time.

I give El Greco’s Nobleman one last glance before departing, and he seems to press his hand a little more firmly to his chest, and dip his head into the slightest of nods in reply. He remains with Las Meninas, Dürer’s Self-portrait, and the countless other portraits, landscapes and sculptures there, to ponder the existential points of life. I am sure the museum’s halls echo with their whispering voices when no one is around.

Such is the power of beauty and imagination, and the museums which house their products. The Prado opened up another world to me every time I stepped through its majestic entrance. It may for you as well.

Author: Jocelyn Murray