Abstract

The aim of this essay is the analysis of the specific language of schizophrenia from a philosophical-psychological perspective. The contribution of philosophy to examining the idiosyncratic language of this disorder is reflected in the reference to the concepts such as self, mind, conscience, subject, and in the acceptance of certain assumptions from the philosophy of language. On the other hand, psychoanalysis underlines the significance of stable borders between a subject and the primary object in early childhood, whose crash can result in the equation between the signifier and the signified, as well as the destruction of semantics and pragmatics, which are characteristic of schizophrenia. Heidegger’s conception of mental disorders will also be explored, in light of his thesis that the Being is based in the language, whose main function is dialogical. It is that function exactly that is absent from Hölderlin’s late verses, which lack words-indicators (deixa). Finally, I will reflect on the attempts at the integration of philosophical and psychological standpoints, which pose a challenge to the traditional conceptualization of the language of schizophrenia.

KEYWORDS: schizophrenia; language; psychoanalysis; cognitivism; Hölderlin

Introduction

The language peculiarity in most cases of schizophrenia attracts attention from researchers in different fields – philosophy, psychology, linguistics, cognitive science, neuroscience. Although speech disorder is not pathognomonic of schizophrenia, as it is also symptomatic of autism spectrum disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, dementia, bipolar disorder, etc., it is one of schizophrenia’s most recognizable features. In Kraepelin’s 7th edition of Textbook of Psychiatry (1904), language and speech impairments were under the name of schizophasia, as a separate form of dementia praecox, the term of the disorder coined by the author. Schizophasia or confusional speech dementia praecox designated “an unusually striking disorder of expression in speech, with relatively little impairment of the remaining psychic activities”. However, the notion of schizophasia today refers to the “word salad”, a “severely disorganized and virtually incomprehensible speech or writing, marked by severe loosening of associations strongly suggestive of schizophrenia.“ Thus, we cannot use Kraepelin’s schizophasia synonymously with schizophrenic language, as the latter encompasses a vast array of specific language disturbances. The linguistic nature of this disorder was acknowledged by Bleuler, too, who renamed it to schizophrenia in 1911 (from the Greek words schizo – split, and phrenia – mind, a split mind). Namely, he included thought and speech derailment (“loosening of associations”), together with volitional indeterminacy (“ambivalence”), affective incongruence, and withdrawal from reality (“autism”), in the category of basic symptoms of schizophrenia. Classic psychiatry ascribed the cause of language alterations to thought disorders or specific cognitive impairments, which could be narrowed down to the derailment of the train of ideas, according to Kraepelin, or to the loosening of associations, according to Bleuler. The term thought disorder would be later substituted for thought disorganization, as a more sensitive concept. However, according to Kuperberg thought disorder could still be used today, only descriptively, to stand for various cognitive characteristics resulting in language modifications. Such cognitive phenomena, whose connection with schizophrenic utterances has been hypothesized are, for example, semantic and working memory capacities, attention, social cognition, theory of mind and mentalization, then decentration and conservation in Piaget’s theory, which are necessary prerequisites for the development of the symbolic thought. It is precisely this symbolic capacity that is destroyed in people with schizophrenia, and, in describing this process, I am going to refer not only to Piagetian abovementioned terms but also to splitting and projective identification, terms introduced by Melanie Klein. Although the classic psychiatric approach to schizophrenic language has historical significance, paving the way to contemporary neuroscience research, I believe that inclination to describe complex schizophrenic discourse in terms of cognitive deficits presents a reductionist and simplifying approach to the problem. Moreover, although the schizophrenic language is oftentimes incomprehensible, it does not mean that it is nonsensical, or that we should refrain from seeking its meaning. This idea represents a radical turn from the traditional tendency to impersonally describe and categorize symptoms of a mental disorder, which can be illustrated with, for example, Andreasen’s classification of 18 speech disorders, indicative of schizophrenia. Phenomenological psychiatry, on the other hand, emphasizes individual’s subjective experiences, such as language, which is understood as a private phenomenon, linked with a distinctive existential mode of a person with schizophrenia. Cardella gives a concise account of the phenomenological approach: “it is through language that the existential modality of someone who suffers from a mental disorder can reveal itself, and therefore the interpretation of what patients say becomes crucial. Language reflects, mirrors, and shows the schizophrenic form of life, but only for those who know where to look.” The underlying assumption of this perspective is the anti-normative conception of mental disorders, by which no clear cut-offs between normality and disorder are postulated and neither one of these is taken as an absolute category. In regard to language, phenomenological psychiatry does not dismiss its meaning as irrelevant, nor does it try to explain it (erklären), as much as to clarify it (aufklären), or understand it. According to Jaspers, a psychiatrist needs to empathize with the patient, and thus gain insight into his or her world of experiences. While doing so, any presupposed causes, theories and conceptions should be “bracketed out”, focusing only on “that which actually exists (in the patient’s) mental life.” In line with this anti-normative, anti-psychiatric understanding of mental disorders is psychoanalysis, which deals with schizophrenia as a semiotic disorder, and with a person with schizophrenia as a text. This is opposed to traditional psychiatry, which supports the normative paradigm and describes language phenomena referring to “a normality that is always implied and never expressed”. In this essay I am exploring the anti-normative approach to schizophrenic language, embodied in philosophy, phenomenological psychiatry, and schools of psychoanalytic thought, while also evaluating attempts of cognitivism at explaining schizophrenic language. But, firstly, I will describe the idiosyncratic language of schizophrenia, though not exhaustively, and compare it across different fields of linguistics (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics).

The language of schizophrenia

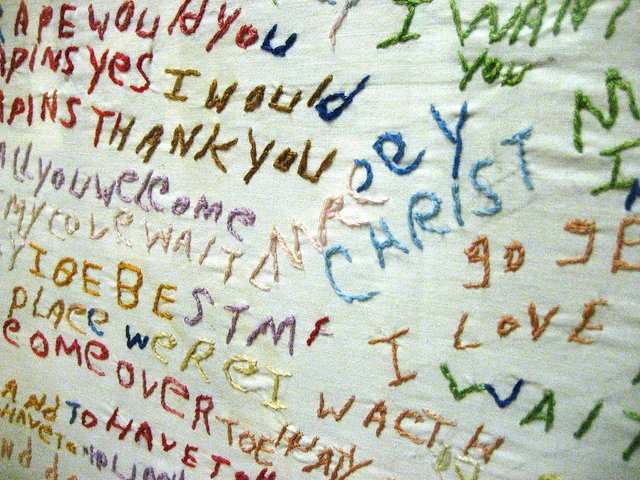

When it comes to the phonological level of language, some people with schizophrenia, especially negative, have a characteristic “creaky and shaky voice that lacks any intonation”, and can also be monotonous, with pauses and hesitations. As to the voice of schizophrenics, equal attention should be paid to their silence. However, this does not have to do anything with phonological disturbances, but to the frustration from language. After failed attempts to express themselves in a comprehensible manner, schizophrenics may decide that it is better not to try any further. While this suprasegmental level of phonology can be disturbed, the segmental level of phonology is mostly intact, as people’s speech resembles the phonology typical of their mother tongue. Thus, Chaika remarks: “In fact, because they are so consistent with the stress and phonemic rules of English, one thinks the patient has actually made utterances of the language which one has failed to catch” Flattened intonation is found to be a common occurrence, as well as the reduced ability to recognize emotional states of others, based on the intonation of their voice. According to Stein, this dull intonation is not due to the absence of emotion, but rather the inability to express it, as participants in her study reported. Another aspect of phonology that seems to remain preserved is verbal fluency, which was tested by asking participants with schizophrenia to say as many words as possible, from a given phonetic category, and they had no problems with the task. The morphological level of language functions mostly in the same way as among people without schizophrenia. Disorder of this kind is very rare, according to Covington et al, and a seldom example is given by Chaika, quoting a patient: “I am being help[ed] with the food and the medicate... You have to be able to memory the process…” In addition, agrammatism and paragrammatism can also appear in schizophrenia, not as its core symptoms, but as a result of the intellectual decline, according to Cardella. Agrammatism refers to the simplification of word parts, usually elimination of pronouns, particles, and conjugations. On the other hand, paragrammatism denotes incorrect usage of prefixes, suffixes, declinations, and conjugations. Thus, Kleist mentions a patient who excessively used the German adjective-forming suffixes –artig and –et. Regarding syntax, it is mostly preserved, even with the destruction of semantics and pragmatics, even in “word salad”: “If we need soap when you can jump into a pool of water, and then when you go to buy your gasoline, my folks always thought they should get pop, but the best thing is to get motor oil…” Now, syntax production can be simplified, and harder to comprehend, but this need not originate from a syntactic defect, but rather from a general intellectual deficit. Some studies conclude that syntactic simplification increases as a chronic patient’s condition worsens. On the other end of the spectrum, the syntax in schizophrenic speech can be hyper-complex, especially in cases of paranoid schizophrenia, according to Pennisi. He provides an excerpt from a patient’s letter, consisting of only one sentence, which should illustrate the point:

“Using certain words, and naming a writer who used, invented one of them, I did not want, as one could believe, to compare myself for expressive juxtaposition in expressing my opinions only, to the field of the theses belonging to a great man of culture, neither I want to say that I include myself in the present, wide, though dead, area of opinions in which he, though criticising me, sang the praises of me, praises judged with discretion and paradoxical, because one word for me wanted to express in the most appropriate way the disdain towards inhuman forms of beliefs which, without differences among parts, are according to me still inhuman, and describable, by the most incontestable terms, for their features of ‘witchy uncertainty’, false science, and inhumanity.”

The semantic domain contains the most distinctive traits of language in this disorder. First of all, according to Vulević, words of schizophrenic patients lose their conventional meaning and are used in an idiosyncratic way. This idiosyncrasy reaches its full realization in the production of new forms, neologisms. One of the earliest depictions of this linguistic phenomenon is offered by Seglas, who distinguished between active and passive neologisms. Active neologisms presuppose a conscious need to convey some meaning that a person cannot find in the language, which is typical of schizophrenia and paranoia. Passive neologisms, on the other hand, are not a result of any conscious attempt but are automatic, involuntary and uncontrollable, often present in catatonic schizophrenia and mania. In Tanzi’s view, active neologisms are connected with delusions, in the sense that newly formed words refer to the delusional system of thoughts. For example, a patient calls Crucipher- his persecutor, or trafusion – the torture inflicted on her by her cousins, or phtaron - particle that constitutes the rays which withdraw his thoughts. Rodriguez-Ferrera et al, who matched the participants on general cognitive ability, found relatively preserved syntax on language tests but modified higher-order semantics, which refers to organization of smaller units of language into bigger structures. Difficulties have been also reported in the task of generating narratives based on pictures, with a lot of irrelevant statements. Furthermore, people with schizophrenia often rely on concrete-pictorial language, due to impaired abstract reasoning, thus a statement “That is too one-eyed to me” is an attempt to express an abstract thought “I cannot fully understand that”. Another characteristic feature is paralogism, which refers to the words that are not used in their conventional sense, but rather out of context, such as the word hill, which stands for letter, in the following sentence: “Dear wife, I reply with pleasure to your hill."

Apart from semantics, a level of language most often altered in schizophrenic speech is pragmatics, which represents relationship between language and context. People with schizophrenia often disregard contextual requirements of a speech or conversation, by providing irrelevant details, changing the topic of the talk, trailing off the subject matter of the conversation, thus making the communication impossible, or using references in a confusing way, for example: (‘He stabbed the dude and I kicked him’; ‘him’ could refer to ‘he’ or ‘dude’). This reduces the coherence of conversation, as a person with schizophrenia follows no plan of expressing ideas, and discourse is “formed by a succession of emissions not necessarily inter-related.” If we remember Grice’s maxims of conversation, as conditions of rational communication, we can pose a question of their application in the speech of schizophrenics. According to De Decker and Van de Craen, and several other authors, schizophrenic language does not follow Grice’s maxims, of quantity, quality, relation, and manner. I will illustrate breach of the principle of quantity, which requires the speaker to make her contribution as informative as required, and no more informative as required:

T: what I don’t understand in your story, is your relationship towards this second Christ?

P3: well I had to submit myself, I was the elder, just like Christ who was born from the family of David, something like that I suppose.

Here, the patient’s account is not informative enough to be understandable.

Having described some language peculiarities, characteristic of schizophrenia, but certainly not exhaustive, I would like to proceed to the central topic of this essay, which is the suggested causes and correlates of such language. I will try to compare and contrast views of cognitivism, philosophy, phenomenological psychiatry, and psychoanalysis, on this matter.

References

Blanken, G., Dittman, J., Grimm, H., Marshall, J., & Wallesch, C-W. (2008). Linguistic disorders and pathologies: An international handbook. Walter de Gruyter.

Cardella, V. (2018). Language and schizophrenia. Perspectives from psychology and philosophy. Routledge.

Covington, M., Congzhou, H., Brown, K., Naci, L., McClain, J., Fjordbak, BS., Semple, J., & Brown, J. (2005). Schizophrenia and the structure of language: the linguist’s view. Schizophrenia Research, 77, 85-98.

Jablenski, A. (2010). The diagnostic concept of schizophrenia: its history, evolution, and future prospects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(3),271–287.

Mueser, K., & Jeste, D. (2008). Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. Guilford Press.

Paul Grice. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grice/ Updated October 19, 2017. Accessed February 28, 2020.

Radanovic, M., Sousa, de RT., Valiengo, LL., Gattaz, WF., & Forlenza, OV. (2012). Formal thought disorder and language impairment in schizophrenia. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 71(1).

Spitzer, M., Uehlein, F., Schwartz, M., & Mundt, C. (1992). Phenomenology, language & schizophrenia. Springer-Verlag.

Vulević, G. (2016). Razvojna psihopatologija. Akademska knjiga.

Wodak, R., & Cran Van de, P. (1987). *Neurotic and psychotic language behaviour. *Multilingual Matters.

Woods, A. (2011). *The Sublime Object of Psychiatry: Schizophrenia in Clinical and Cultural Theory. * Oxford University Press.

Word salad. APA Dictionary of Psychology . https://dictionary.apa.org/word-salad Accessed February 25, 2020.

Wrobel, J. (1990). Language and schizophrenia. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

HIVE IS ALIVE!!!

JOIN US, YOU'LL HAVE EXACTLY THE SAME BALANCE AS YOU HAVE HERE ON STEEM WITHOUT THE CENTRALIZATION AND CENSORSHIP!!

https://hive.blog

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit