The revival of Fender’s blue illustrates the collaborative nature of survival.

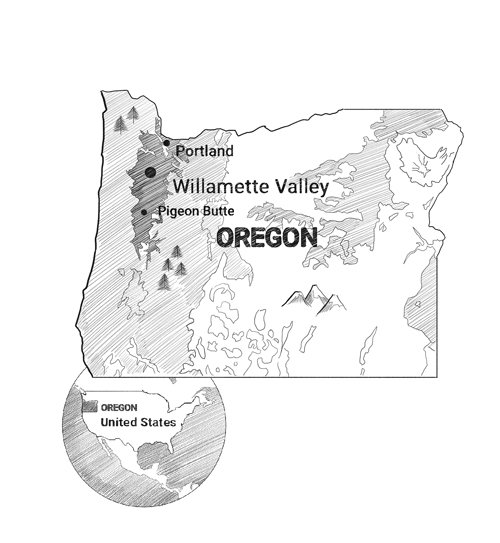

From the top of Pigeon Butte in western Oregon’s William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge, the full width of the Willamette Valley fits into a gaze. Slung between the Coast Range and the Cascades, the valley is checkered with farmland: grass-seed fields, hazelnut orchards, vineyards. In the foreground, however, grassy meadows scattered with wildflowers and occasional oaks trace the land’s contours.

Upland prairie landscapes like these once covered 685,000 acres of the Willamette Valley. By 2000, only a 10th of 1% remained. Their disappearance has meant the decline of countless species that once thrived here; some are endangered, others have disappeared. Among the nearly lost is a nickel-sized butterfly called Fender’s blue.

Endemic to this valley, Fender’s blue was first collected in 1929. Shortly thereafter, it vanished, and, for 50 years, no one could find the sapphire-winged insect; it was presumed extinct. But in 1988, a 12-year-old boy netted a few in a meadow outside Eugene, and a lepidopterist officially rediscovered the butterfly the following year. It was added to the endangered species list in 2000, when fewer than 3,400 remained.

Now, the butterfly’s population has quadrupled and the species is slated to be downlisted from endangered to threatened. If this status change is finalized, as is expected to happen this year, Fender’s blue will become only the second insect to have recovered in the history of the Endangered Species Act.

I’d come to the Pigeon Butte prairie one May morning in search of Fender’s blue because I wanted to see firsthand the particular beauty of this rare butterfly. But also, at a time when an estimated half-million insect species worldwide face extinction and butterfly populations are shrinking at unprecedented rates, I wanted to witness the thing this creature represented — proof that amid such overwhelming loss, recovery, too, remains possible.

It wasn’t until I’d given up and started back down the hill that I saw them: two blue butterflies circling near my knees. When one landed, I peered at the underside of its wing and found the double arc of black spots that differentiate Fender’s blue from its more common look-alike, silvery blue.

.jpg)

My first thought was one of wonderment: How had this delicate creature, with its tissue-thin wings and sunflower-seed sized body, come to be flitting about on this spring morning nearly 90 years after it was declared lost forever? My second thought was less romantic: So what? In the face of an ecological crisis of such grand scale, it was hard to imagine what difference the survival of one small blue butterfly might make.

A FEW YEARS AFTER the rediscovery of Fender’s blue, a graduate student named Cheryl Schultz found herself just outside Eugene, slogging through blackberry brambles taller than her head. Here, at what is now a Bureau of Land Management area called Fir Butte, pockets of remnant prairie persisted among a snarl of woody invasives. In these openings a few dozen Fender’s blues resided. Today, much has changed, and the site hosts more than 2,000.

Schultz, now a Washington State University professor, has helped lead Fender’s conservation for nearly three decades. But as a kid, she didn’t carry around a butterfly net. Instead, she came to butterflies by way of her interest in something else. She started her career in the years following the fiercely divisive debate over the addition of the northern spotted owl to the endangered species list. The fight pitted environmentalists against the timber industry and framed the issue as an either/or battle of good versus evil, jobs versus owls. Schultz grew wary of such dichotomies. She wanted to explore how science could help wildlife and people better share a landscape.

“Recovery takes three things. Science, time and partnerships.”

Trying to save Fender’s blue offered a challenge well-suited to this line of inquiry. Biologists knew the butterfly’s limited habitat would need to be expanded to prevent its extinction, but its range overlaid a landscape dominated by the human endeavors of agriculture, urban development and private land ownership.

Schultz began by observing Fender’s blues to better understand their particular ecology: How far will a Fender’s travel? How much nectar is needed to support a population? How do fires and herbicides affect the species? Then, she and her colleagues used their findings to help develop the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fender’s blue recovery plan. But science alone, Schultz told me, cannot enact conservation. “Recovery takes three things,” she said. “Science, time and partnerships.”

PERHAPS THIS STORY OF RECOVERY begins not with an insect but with a plant: Kincaid’s lupine, a perennial wildflower with palm-shaped leaves and spikes of muted purple blossoms. Like many butterflies, Fender’s blue exists in tight relationship with a particular host plant. From the moment a Fender’s caterpillar hatches in early summer until it unfurls from its chrysalis as an adult butterfly the following spring, the host plant — almost always Kincaid’s lupine — provides its sole source of food and shelter. “They’re a species pair,” Tom Kaye, the executive director of the Corvallis-based nonprofit Institute for Applied Ecology, told me. “To conserve the butterfly, you have to conserve the lupine.”

After the butterfly’s rediscovery in 1989, researchers began searching for Kincaid’s lupine. Like the insect, the plant was exceedingly rare. It grows in upland prairies, ecosystems comprised of grasses and forbs that build soil and, unless something interrupts the process, eventually give way to shrubs and trees. To remain prairie-like, a prairie requires disturbance.

In the Willamette Valley, that disturbance historically came in the form of fires managed by the Kalapuya people, who burned the prairies regularly to facilitate hunting and sustain plant communities that provided crucial foods, including camas and acorns. When settlers displaced the Kalapuya via disease, genocide and forced removal, burning ceased. The long-tended prairies, invitingly flat and graced with a mild climate and plentiful water, were swiftly plowed under for agricultural fields and turned into settlements.

“To conserve the butterfly, you have to conserve the lupine.”

Without fire, what little prairie habitat remained began to transform: Hawthorn and poison oak encroached, fir and ash trees took root, and the diversity of grasses and flowering plants that had once flourished — including Kincaid’s lupine — withered.

Researchers at the Institute for Applied Ecology have been studying Kincaid’s lupine in an effort to reverse that trend since the organization’s founding in 1999. Many of the conservation strategies they’ve developed have to do with the ways the lupine interacts with its environment, such as the symbiotic relationships it forms with mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobium bacteria. Rhizobium live in nodules attached to the lupine’s roots, where, in exchange for nutrients, they provide the plant with a steady supply of fixed nitrogen. In new restoration sites where these fungal and bacterial partners are scarce, inoculation with soil from areas currently supporting robust lupine populations can bolster the new plants’ chances of success.

On a June afternoon, Kaye and I stood amid rows of flowering plants at the organization’s seed production farm. The lupine was nearly ready to harvest, and Kaye lifted a pod and held it skyward. Sunlight flooded the husk to reveal the dark orbs of just two seeds cupped inside. Kincaid’s lupine, he said, produces scant seeds, especially in the wild, where predators such as weevils abound. That made it nearly impossible to collect enough for restoration. “I could hold in my hand the entire seed output of a population,” Kaye told me. “Meanwhile, from a production field I could fill bags.”

So he and his colleagues sought ways to boost the cultivated supply. In collaboration with the Sustainability in Prisons Project, the organization established a seed production field inside the Oregon State Correctional Institution. Through this program, incarcerated people have produced tens of thousands of Kincaid’s lupine seeds, and, by extension, adult plants that now host Fender’s caterpillars in restored prairies across the Willamette Valley.

ONE LATE MAY MORNING, I met Soledad Diaz, an ecologist with the Institute for Applied Ecology, at Baskett Butte in the Baskett Slough National Wildlife Refuge. Here, in one of the Willamette Valley’s largest restored Fender’s prairies, I found her crouched with a crew of sun-hatted researchers, counting flowers to estimate available nectar resources.

Diaz gestured to my shoulder. I spun around to watch the flicker of a Fender’s blue as it flitted off and landed upon a nearby lupine. “Looks like an old one,” Diaz said, pointing out the tattered edges lacing the butterfly’s wings. In the life of a Fender’s blue, “old” means just nine or 10 days. On the slopes around us, knee-high grasses rippled and flowers bloomed: checkermallows, mariposa lily, Oregon iris, plenty of host lupine. Blue butterflies flew from plant to plant with such carefree buoyancy it was hard to remember they were urgently attending to the task of finding nectar and a mate under the ticking clock of their brief lifespan.

.jpg)

Most remnant populations of Kincaid’s lupine are found on hills like Baskett Butte, explained Graham Evans-Peters, the Baskett Slough Refuge manager. Because steeper terrain makes farming difficult, landowners historically used these uplands for livestock rather than crops. Grazing cattle, like fires, keep woody encroachment at bay and mow down tall grasses. And, Evans-Peters told me,

“They don’t like lupine.”