There's roughly two stages of studio work: recording and mixing. A lot of ska and rocksteady was recorded with one microphone hanging in the centre of the studio, and released as a mono record. But by the late 60s studios had two or four-track recording, so the possibilities for mixing a track grew, and studio engineers like King Tubby could take a studio mix, drop in and out the drum and bass track, or the guitar and keyboards, or the vocals, and add echo and delay, sometime creating entirely new landscapes.

I remember first listening to Bill Laswell's ambient dub mixes of Bob Marley and the Wailers' songs, and not being able to recall the names of familiar tunes, because the dub mixes were somehow something else entirely. In early dub the psychedelic soundscapes were stripped back and atmospheric, sometimes nothing more than a few unmelodious notes of bass and a spare drumbeat, but the grooves coming out of Kingston studios were so sinewy and tight that the exposure only added an otherworldly beauty to the music.

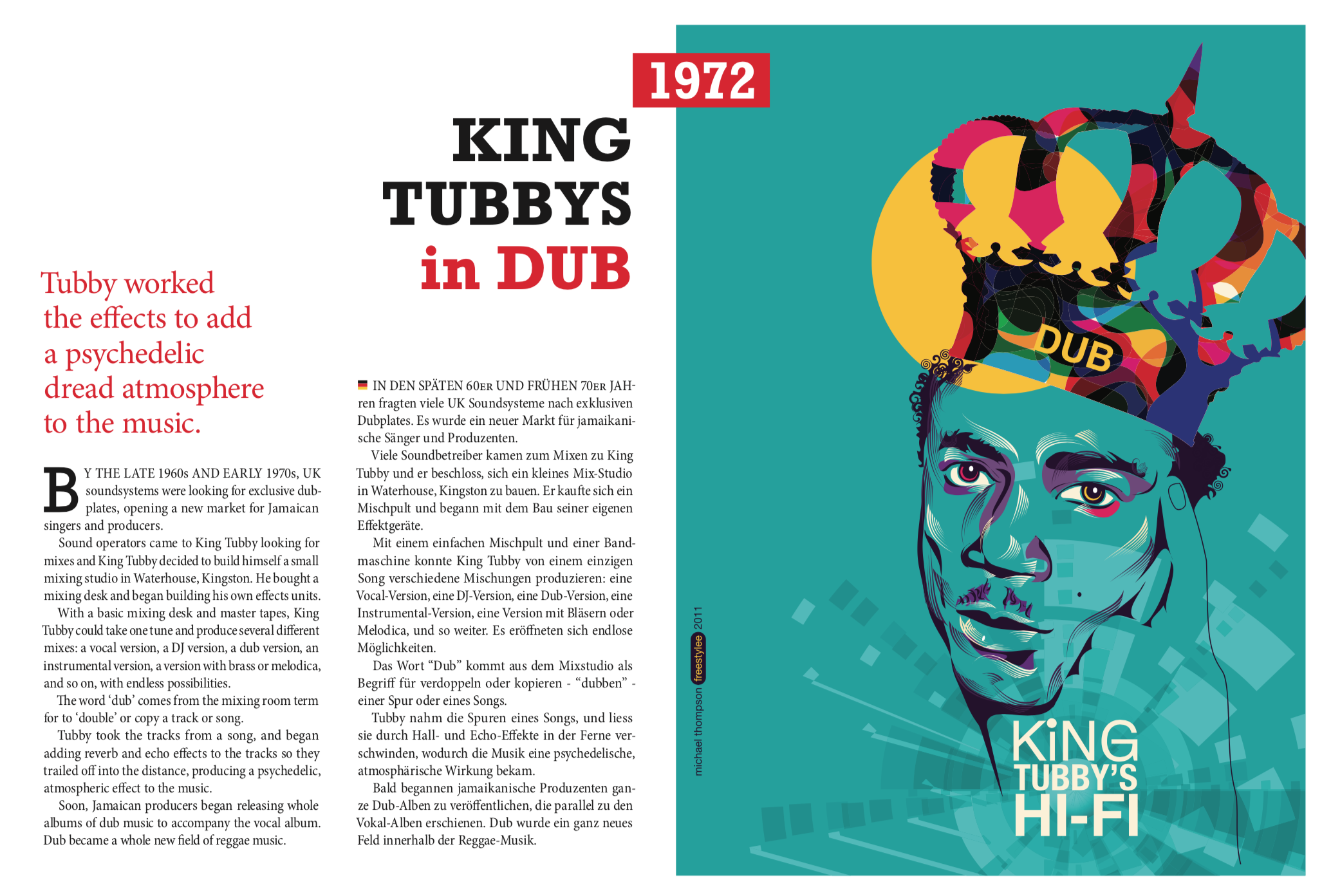

Within a couple of years of the emergence of roots reggae the dynamic was already firing off new and radical developments - and not just in reggae music. King Tubby was one of the first to grasp the potential of remixing a tune, which became industry practice. The panel is King Tubby done by Freestylee: check this Tubby mix of the Lee Perry and the Upsetters production Blackboard Jungle.