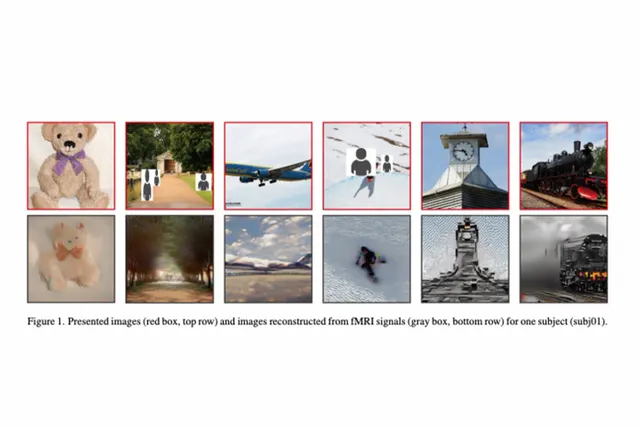

A.I. re-creations of images captured by brain scans (bottom row) and original images (top row).

YU TAKAGI AND SHINJI NISHIMOTO, OSAKA UNIVERSITY VIA CREATIVE COMMONS

Artificial intelligence has gotten scary good. It can already pass major medical exams, arrange friendly meetups with other A.I. online, and when pushed hard enough can even make humans believe that it’s falling in love with them. A.I. can even generate original images based only on a written description, but even that may not be the limit of its potential—the next big development in A.I. could be understanding brain signals and giving life to what’s going on in your head.

Machines that can interpret what’s going on in people’s heads have been a mainstay of science fiction for decades. For years now, scientists from around the world have shown that computers and algorithms can indeed understand brain waves and make visual sense out of them through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines, the same devices doctors use to map neural activity during a brain scan. As early as 2008, researchers were already using machine learning to capture and decode brain activity.

But in recent years A.I. researchers have turned their attention towards how artificial intelligence models can replicate what’s going on in human brains and display people’s thoughts through text, and efforts to replicate thoughts through images are also underway.

A pair of researchers from Osaka University in Japan say they have created a new A.I. model that can do just that, but faster and more accurately than other attempts have been able to. The new model reportedly captures neural activity with around 80% accuracy by testing a new method that combines written and visual descriptions of images viewed by test subjects, significantly simplifying the A.I. process of reproducing thoughts.

Systems neuroscientists Yu Takagi and Shinji Nishimoto presented their findings in a pre-print paper published in December that was accepted last week for presentation at this year’s Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition in Vancouver, one of the most influential venues for computing research. A CVPR representative confirmed to Fortune that the paper has been accepted.

The novel aspect of Takagi and Nishimoto’s study is that they used an algorithm called Stable Diffusion to generate images. Stable Diffusion is a deep learning text-to-image model owned by London-based Stability AI that was publicly released last year, and is a direct competitor to other A.I. text-to-image generators like DALL-E 2, which was also released last year by ChatGPT creator OpenAI.

The researchers used Stable Diffusion to bypass some of the stumbling blocks that have made previous efforts to generate images from brain scans less efficient. Previous studies have often required training new A.I. models from scratch on thousands of images, but Takagi and Nishimoto relied on Stable Diffusion’s large trove of data to actually create the images based on written descriptions.

The written descriptions were made with two A.I. programs created by Takagi and Nishimoto. The researchers used a publicly available data set from a 2021 University of Minnesota study that compiled the brain waves and fMRI data of four participants as each viewed around 10,000 images. That fMRI data was then fed into the two models created for the study to create written descriptions intelligible to Stable Diffusion.

When people see a photo or a picture, two different sets of lobes in the brain capture everything about the image’s content, including its perspective, color, and scale. Using an fMRI machine at the moment of peak neural activity can record the information generated by these lobes. Takagi and Nishimoto put the fMRI data through their two add-on models, which translated the information into text. Then Stable Diffusion turned that text into images.

Although the research is significant, you won’t be able to buy an at-home A.I.-powered mind reader any time soon. Because each subject’s brain waves were different, the researchers had to create new models for each of the four people who underwent the University of Minnesota experiment. That process would require multiple brain scanning sessions, and the neuroscientists noted the technology is likely not ready for applications outside of research.

But the technology still has big promise if accurate recreations of neural activity can be simplified even further, the researchers said. Nishimoto wrote on Twitter last week that A.I. could eventually be used to monitor brain activity during sleep and improve our understanding of dreams. Nishimoto told Science this week that using A.I. to reproduce brain activity could even help researchers understand more about how other species perceive their environment.