A question from interview to Mikael Haneke asks why he has so much violence in his movies. In Hollywood, he replies, violence is a consummation that the spectator is pressed to chew, process quickly, and eventually throw out of his system. Blood in Hollywood doesn’t shock, it's entertaining. The result is that after the movie, the viewer is drugged, the assured version is better - life is nice, comfort is everywhere. According to Haneke, this is a manipulation that doesn’t lead to any change - you enter a consumer and go out a consumer; you didn’t edit the movie in a question, didn’t shape the violence - which is so important to the reality issue - in a question. And you watched a movie. Isn’t the cinema the art that has the power to serve the most complex issues in the most accessible way?

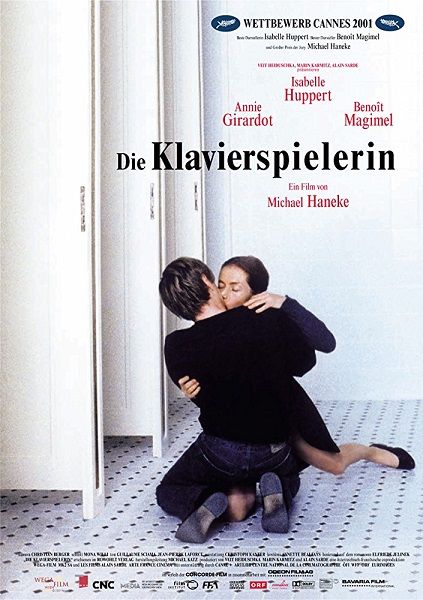

I remember the first time I watched "The Piano Teacher"(2001), I was 19 and the film didn’t impress me. I found it disgusting, I felt that if it hide meaning, I was not called to it. Because of the inability to understand it, I decided to forget it. About a month ago, 29 years old, I looked at it again. It hit me with the power of a nightmare that lurks in the mind and doesn’t leave it for days after being dreamed. I also read the book for which the Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2004. "The Pianist" is a very specific book from which Haneke made a very specific movie. The theme, the heart of the story, is everywhere in every scene. But it was not easy for me, even though it was in front of me, to make it clear. What is this story about? Violence? The pursuit of pain? After a few days of chewing, it occurred to me. Control. It's a movie about control. In the original, the title of the book is "The Pianist" and the English translation is "The Piano Teacher". The strange thing is that the "teacher", which is a kind of interpretation of the title, is much closer to the specificity of the book: Erika Kohout (Isabelle Yuper) is not a concert pianist, she is just a piano teacher at the Conservatory in Vienna. She hasn’t got any man, she lives with her mother, sharing a bed with her. Jelinek in the book calls her bedroom "marriage bed", where the 40-year-old "child" falls to her mother every night. Mother (Annie Girade) determines her child's everyday life - Erika gets home after work at home, never gives extra money for short (over ankle) dresses with floral motives (vanity is for the frivolous, for "toad frogs") and does not respond the poisoning looks of any men, because they are a deep trap that sucks straight to mediocrity, but only one thing is important: Erica must be great. Erica is a suppressed creature that carries the cracked armor of an authoritative teacher every day. She clutches all her students with the coolness her mother has been doing for years. Neither does the pear fall further from the tree, nor can the train come out of its designated rails. But in the story - both in the book and in the movie - this relationship of power and aggression between mother and daughter is only a stop on a longer journey; and one of the stations is the only main male character in history - the young Walter Klemer (Benoa Mazimel), a student of Erika Kohout. The game starts right away, with the first date. They play it together, lose it separately. I remember, if anything, when I was 19 and watching the movie, I fell a lot on Clemer (rather on Benoit Maghimel, who is the best actor at the Cannes Festival). Rus, furious, plays Schumann and Schubert. The is an athlete. He is congratulatory. He is polite. Ideal. Erica couldn’t admit that someone was perfect. Ideal are the dead, whose works echo through eternity in concert halls. Anyone who does not practice art is mediocre. Moreover, terribly many who have the pretense of dealing with art are also mediocre. Erica could conclude that people are defective, smudged flesh bags (there is one point in the book, how she rides in the subway and the gun and bums in the ribs of casual people, supposedly casually). To his students, colleagues, to the entire population of Vienna, Erika watches with disgust, and when she is in a better mood - with regret.

Walter Klemer invades her life like a summer storm - spontaneous but waiting. When he hears her playing, he immediately states that he wants to study in her class. He spoke to her without a shame, watching her in the eye, stretching her wishes unambiguously to her. He is hers. He loves her. She as a teacher and as a woman can do whatever she wants. Erika does not seem to give up, but her world has changed from the first conversation with him. She dreamed this man, his determination and strength; to merge its majesty with hers. (Erica successfully perceived the role her mother had, she had no choice but to listen to the one that created her - if she was not great, what else did she remain?) The scene in which Clemer goes out the commission of an examination to enter the Erika class is indicative: Erika does not think that this young man is as talented as her fellow professors do; BUT it is still captured by its firmness, the energy with which it pursues its purpose; Walter Klemer shines, and Erika falls under that beam, and she's shining. Do not be misleading - it's not a love story. Neither in the book nor in the movie (who is faithful to his literary source and allows himself to change only one or two pieces to serve the filmmaking of the story), there is not one character who is sympathetic. No personality is inspired by the lightness of love affection. Love should have a transforming power, and Erika and Clemer at the end of the story are far more distant than they were at the beginning. Love in the Pianist is a lie that serves to expose anguished truth - sometimes when it says that he loves the other, a man without knowing says he loves control over the other. Hahneke says he believes violence is always caused by fear. An abuser is the coward, who lacks either experience or knowledge. Erika's mother (who does not have a name, she's just the Mother, bursting to her mother's burst) is terrified of loneliness. Her husband has died in a madhouse and remains her only daughter. To such an extent, she clings to her that she has made her an appendage, most likely without realizing the consequences of this disastrous relationship. The mother is sitting at home all day and thinks her daughter. She prepares dinner, watches TV, and counts Erika's steps toward home. (The TV is constantly making noise, an intense often used decor in Haneke's films, a box which, as Marshall McLuugh writes, speaks without saying anything, and I suspect that for Haneke mass media and television are a sick subject, the director has worked 21 years in television, before he finally got to the movies at the age of 46.)

The mother is the beginning of Erica's Control. The poison with which she lives, the death that is being experienced. Once rooted, the mother's will crawls through the veins of Erica. Regarding one of the most shocking scenes in the film, Haneke tells Isabelle Yupper: "Isabel, the strong scene in the cinema is what makes the viewer look away from the screen because it can not stand it." In short: Evening. Erika and mother are in bed. Erica undergoes an emotional collapse, and kisses her mother, fingers her old chest, tries to undress her while she tells her all the time that she loves her. You are afraid to watch, to observe the unthinkable. Like that closed door to the dungeon in the French fairy tale "The Blue Beard," where the King forbids his new wife to enter. The woman, dying of boredom and curiosity, unlocks the room and sees the bodies of seven ex-wives. And this is a scene that is forbidden - it should not be seen, and on the other - it can not be seen. The new woman should open the door, otherwise there will be no climax, no story. So in the "Pianist" - Jelinek and Haneke force you to show you the most disgusting. Confrontation with fear. In the final stage of Lars von Trier's "Nymphomaniac" the characterof Stella Skarsgard tries to rape the main character. The film shows the development of friendship between the two - she needs a listener and support, and he needs someone to protect. In the end, however, the abyss between them proves to be incomprehensible. He listens to her story but does not understand her. All their proximity, therefore, is a fake. A similar feeling left me the moment in the Pianist, when Clemer disgusted leaving Erika's room, telling her: "You are sick. You need treatment. "The stamp that Klemmer is distinguished from her - she's sick, and he's healthy. She needs treatment, and he needs love. Normal, healthy, even banal love, but love. In fact, Clemer is actually the worst. When she is open and wounded in front of him (as he has most probably so far wanted), he takes advantage of her weakness and hates her unappealingly. He does not seek explanation, he does not offer support. He is a little angry little boy who has got a faulty toy instead of a new one and shiny as promised.

The Pianist has no positive emotion that is not perverted to its absolute anthony. The parent is a slave, the teacher is a oppressor, the lover hates after swearing that he loves. Society is passive, art is a torture. Only the dead are great. All this tangle of reddish beauty, poisoning every source of joy, makes both the book and the movie terrible. The film ends with a deadly silence, no music during the captions. I've always thought that whatever film I look at, the music finally puts the final point: "It's a fiction." She's just looking at fiction, not real life. "While in the Pianist, however hyperbole in his cruelty fiction is very real. The silence at the end of the film puts no point, but a heavy exclamation point: "Here's what's all about. Here's where love is dead. "

Wonderful review of a deeply disturbing film that left me sleepless for days.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

What a movie and what a review @godflesh!

I saw it a looong time ago. It brought back so many memories :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Glad to hear that, Abigail :)

Well, now I make a film marathon with Haneke's films and still adore movies like "Funny games" and "The Cache". And I am still searching for his adaptation of Kafka's "The Castle" and still cant find it :D

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Wow mate! Very descriptive review with the right perception.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Good review.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

thank you :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks for the review. I didn't know about the movie,I only read the book long ago and I found it slightly disturbing

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

The movie is really a masterpiece. I recommend it to you :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

good post, I like your post ..

I need your support please visit my blog https://steemit.com/@muliadi

https://steemit.com/busy/@muliadi/colorchallenge-tuesdayorange

if you like my post please give upvote, resteem &follow me.

thank you, keep on steemit.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

:)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit