I adored Masha Gessen’s book prior to this one, i.e. The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia. She wrote succinctly and sobering about how Russia worked, has worked, and might work in relation to totalitarianism.

This time, she is focusing on America in the age of Donald Trump, although it is more than easy to compare the aforementioned countries. Here is an early quote from the book that easily puts the finger on all of what is great about Gessen’s writing:

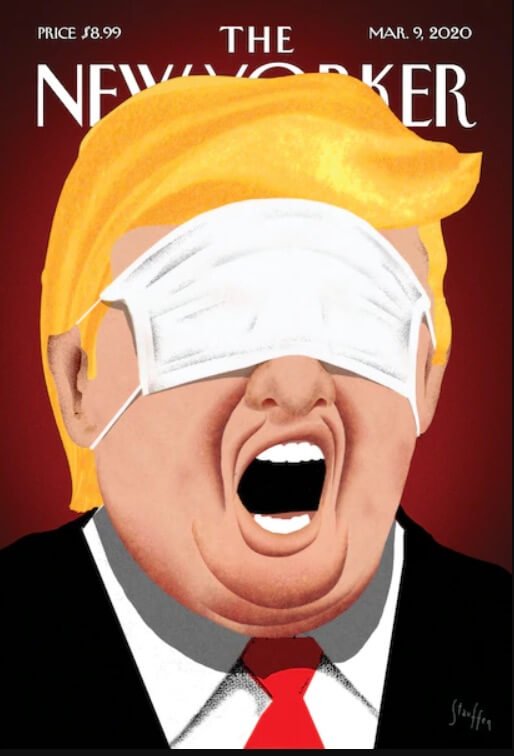

Trump apparently read from a teleprompter that night. He sounded grave. This was, in other words, one of those times when Trump sounded presidential to some people, because he didn’t sound entirely deranged. For example, former Ohio governor John Kasich, a Republican, defended Trump on CNN, saying that “he did fine,” in part because he read from a script. But precisely because Trump was not at his worst—just his ordinary obfuscating and self-aggrandizing self—in the extraordinary situation of the pandemic, what we were witnessing was peak Trump.

Over the next few weeks, Trump would shirk responsibility for the crisis, at one point saying literally, “No, I don’t take responsibility at all,” when he was asked about a lack of access to testing. He would tell governors to figure out their own ways of procuring supplies, and he would offer no guidance on policy. He would take the podium at the White House during almost daily briefings and issue bogus medical advice, such as extolling the virtues of untested drugs, which some people then rushed to use. He would resist calls to invoke the Defense Production Act, to compel companies to turn their facilities over to manufacturing essential equipment, evidently for fear of cutting into the profits of his corporate cronies. All along, he would praise his own intelligence and approach. The television networks would broadcast these sessions live; the newspapers would report on them, and Trump’s other coronavirus-related pronouncements, as though they were the stuff of an intelligible presidency, with positions, principles, and a strategy. As a result, even as hospitals across the country buckled, people died, and the economy tanked, more than half of all Americans claimed to approve of Trump’s response to the pandemic.

Some people compared the Trumpian response to COVID-19 to the Soviet government’s response to the catastrophic accident at the Chernobyl power plant in 1986. For once, such a comparison was not far-fetched. The people most at risk were denied necessary, potentially lifesaving information, and this was the government’s failure; there was rumor and fear on the one hand and dangerous oblivion on the other. And, of course, there was unconscionable, preventable tragedy. To be sure, Americans in 2020 had vastly more access to information than did Soviet citizens in 1986. But the Trump administration shared two key features with the Soviet government: utter disregard for human life and a monomaniacal focus on pleasing the leader, to make him appear unerring and all-powerful. These are the features of autocratic leadership. In the three years of his presidency, even before the coronavirus pandemic, Trump had come closer to achieving autocratic rule than most people would have thought possible. This is a book about that transformation—and about the hope we may yet have for emerging from Trumpism.

Trumpian news has a way of being shocking without being surprising. Every one of the events of that week was, in itself, staggering: an assault on the senses and the mental faculties. Together, they were just more of the same. Trump had beaten the government, the media, and the very concept of politics into a state beyond recognition. In part by habit and in part out of a sense of necessity, we continued to report the news and consume the news—this presidency produced more headlines per unit of time than any other—but at the end of each of his thousand days of presidency we seemed hardly closer to understanding what was happening to us.

I’ve written more about that in this blog post.

Gessen starts her narrative by noting how language can be skewed. ‘Every president is a storyteller-in-chief’, she notes, while building a timeline that shows how Trump has not only bullied his way through power, but made sure that his media, his pundits, and White House correspondents all try to follow his lead in different and deranged versions of follow the leader.

Part of Gessen’s greatness consists in her ability to paint a sobering picture by use of facts. Where Trump has spoken on COVID-19—as used at the start of this review—she paints a picture using his words, his administration’s actions, and those of scientists, and place them in a line.

To read Gessen’s words is like experiencing a waft of cool air on a hot summer day: it is genuinely needed in a time where a racist, deceitful, demagogical, misogynistic, capitalistic, and mad person is the president of the USA.

The Trump campaign ran on disdain: for immigrants, for women, for disabled people, for people of color, for Muslims—for anyone, in other words, who isn’t an able-bodied white straight American-born male—and for the elites who have coddled the Other. Contempt for the government and its work is a component of the disdain for elites, and a rhetorical trope shared by the current crop of the world’s antipolitical leaders, from Vladimir Putin to Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. They campaign on voters’ resentment of elites for ruining their lives, and they continue to traffic in this resentment even after they take office—as though someone else, someone sinister and apparently all-powerful, were still in charge, as though they were still insurgents. The very institutions of government—their own government now—are the enemy. As president, Trump went on to denigrate the intelligence services, rage against the Justice Department, and issue humiliating tweets about officials in his own administration.

Gessen shows how Trump chose people who were opposed to the work, and sometimes to the very existence, of the agencies they were appointed to lead.

They couldn’t be bothered with the conventions of government because they found government itself contemptible.

Gessen builds a stronghold of sanity as she briefly reduces the myriad of insane actions of leaders of autocracies. Even though I don’t think we shouldn’t blame Trump for all of this, it’s clear that insane leaders use ranting and filibustering as a method of control.

Trump’s incompetence is militant. It is not a factor that might mitigate the threat he poses: it is the threat itself.

Gessen has power in deciphering what Trump says without going into the maelstrom that is his word salad.

I love how Gessen describes Trump’s transparency:

Corruption would not be the right word to apply to the Trump administration. The term implies deception—it assumes that the public official understands that they should not benefit from the public trust, but, duplicitously, they do it anyway. The opposite of corruption in political discourse is transparency—indeed, the global anticorruption organization calls itself Transparency International. Trump, his family, and his officials are not duplicitous: they appear to act in accordance with the belief that political power should produce personal wealth, and in this, if not in the specifics of their business arrangements, they are transparent.

When the coronavirus came, the Trump administration followed the logic of competition, and profit. Officials tried to persuade a German company working on a potential vaccine to sell it first—and perhaps exclusively—to the United States. Rather than coordinate the production and distribution of ventilators, the federal government created a system whereby states bid against one another and the federal government. Trump gave Jared Kushner broad authority to organize a private-sector response to the pandemic, working in parallel with or around the government effort. In other words, Trump acted in ways that would be unthinkable for a political leader, a man entrusted with the welfare of millions of people—but his administration uses a different calculus and makes no secret of it.

To say that this book is current is true. Just see what Trump said yesterday, during his rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma:

Trump’s use of the term “Kung Flu” was previously condemned by White House counselor Kellyanne Conway in March as “highly offensive” after reports said administration aides used the racist terminology.Ellen CranleyTrump's Tulsa rally was a tour of his most misleading and racist comments about coronavirusGo to text →

To return to the title of this book and Trump’s transparent kleptocracy:

Trump praised the mastery with which Kim Jong-un had solidified power in North Korea: “He goes in, he takes over, and he’s the boss.” Later, preparing for an in-person meeting with Kim, Trump claimed, “We fell in love.”

Trump invited Philippine dictator Rodrigo Duterte to the White House and lauded him for his war against drugs, a campaign of extrajudicial executions that had killed thousands.

For his first trip abroad, Trump chose Saudi Arabia, where he received an honorary gold collar from the king. A year and a half later, dissident Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who had been living and working in exile, was murdered inside the Saudi embassy in Istanbul, on orders from and with the knowledge of Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Trump’s statement in response to the murder was titled “America First!” and reaffirmed his friendship with the Saudi royal.

Trump’s second foreign trip was to Israel, where he was greeted on arrival at the Tel Aviv airport by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. They addressed each other as Donald and Bibi. Before the year was out, Trump issued a proclamation recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and ordering that the embassy be relocated there—in contravention of international law and policy consensus. In 2019, the United States took another step, effectively declaring that international law did not apply to the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

Early in the presidency, Trump hosted Chinese dictator Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago. Over dessert—“the most beautiful piece of chocolate cake that you have ever seen,” according to Trump—he told Xi that the United States had just bombed Syria. Fox News put up a split screen: Trump recalling the conversation on the left, missiles exploding in the night sky on the right. It was the perfect pictorial encapsulation of Trump’s understanding of power: raw, brutal, unitary, and performative. Trump is always playing an exaggerated idea of himself on TV.

There are plenty of Trump-related subjects from where Gessen draws her picture of current-day USA: how Trump hates immigrants; the climate crisis; the Mueller report; whistleblowing; Sarah Sanders’s bullying of reporters; Trump’s love of conspiracy theories, and, perhaps most damning of all, how modern media started adhering to Trump’s language.

I’ve written about how people started dancing to Trump’s tune in this prior blog post, and it is important to bear in mind that some companies, for example NPR and The New York Times, refused to use the word ‘lie’ and ‘racist’ about Trump.

This causes an anodyne environment, one where the culprit (Trump) and his cohorts (his ever-replaced cabinet-of-ministers) aren’t answering to what they do.

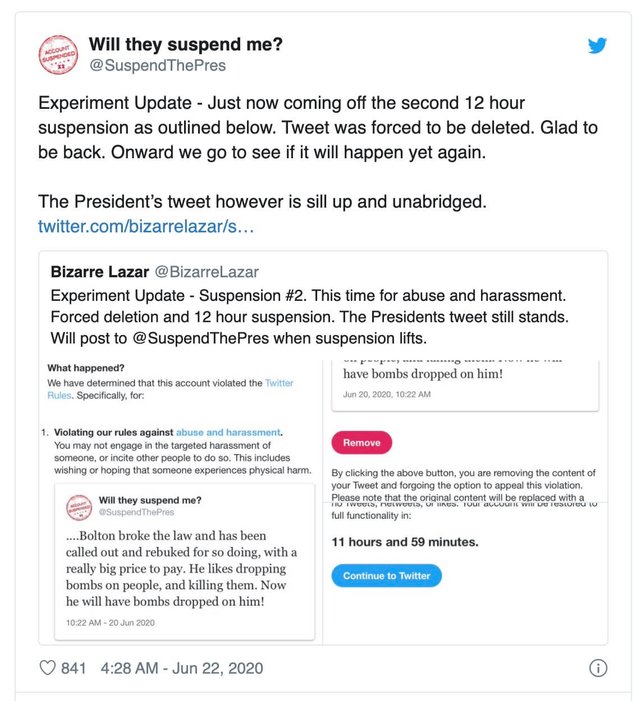

From Will they suspend me?, a Twitter account that retweets what Trump tweets.

From Will they suspend me?, a Twitter account that retweets what Trump tweets.

Several of this account’s tweets have led to the suspension of this account – but not Trump’s. This tweet: https://twitter.com/SuspendThePres/status/1274891976639279104

These are typical reactions from companies like those mentioned above. Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, et al, all gain financially from giving the far-right politicos free reign, as they do.

Gessen has thoughts on this, too:

There have been exceptions in the mainstream media, of course—not only in the more nimble genre of podcasts but inside the venerable old institutions themselves. David Fahrenthold, a reporter with The Washington Post, uses a radically transparent approach to investigative reporting: he asks for tips and follow-up information on Twitter, openly corresponds with informants, and allows followers to stay abreast of his thinking and reporting. He tweeted, for example, “Update: I am still looking for 9 of the 12 sites supposedly vetted for the G-7. The White House says they were in these states, but won’t say where. Let me know if you know something!” He followed up with a tweet saying, “@realDonaldTrump said the frontrunner was his own golf club in Doral, Fla. But is that the final choice? Not clear. The Doral mayor says they’ve still heard nothing.”

The approach is not only a strikingly effective method of crowdsourcing—Fahrenthold won a Pulitzer for his reporting on Trump’s charities—but it also revolutionizes the relationship between a journalist and his readers. Fahrenthold positions himself on the side of the readers: together, they are digging into Trump’s business. The relationship between the journalist and the president is explicitly adversarial, and the relationship between the journalist and the readers is one of actual, observable cooperation.

Most American journalists and editors would agree that this is as it should be—the journalists are working on behalf of the public, and their relationship with power should not be overly cozy—but in reality, the tone of neutrality, authority, and restraint that legacy publications adopt has a way of shifting the journalist away from the public and toward the person in power, making them act more like go-betweens than representatives of one side and one side only. That makes the media ill-equipped to resist the autocrat’s project of coming to dominate the communications sphere.

I will end this review by saying that this book is a must-own, a true call to action, a swift and sobering kick to the head, and necessary truths in the face of lies and irrational thought against the betterment of people.

To end, in Gessen’s words:

Now that the pandemic, aided by Trump, has stripped our politics and our society to the bare basics, the question facing Americans is, What do we want our future to look like? Will we, as we did after 9/11, sacrifice civil liberties and human rights? Will we, as we did in response to the financial crisis of 2008, create even greater wealth inequality? Will we, in other words, choose solutions that exacerbate the root problems? In 2020, that would mean forfeiting more freedoms, accepting ever greater inequality, and reelecting Trump. Or will we commit ourselves to reinvention?