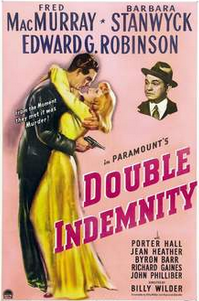

The film noir masterpiece "Double Indemnity" has some spicy lines: “They’ll hang you just as sure as ten dimes will buy a dollar,” and “I’m shaking like a leaf, but it’s straight down the line for both of us, baby” are two of my favorites. Directed by Billy Wilder, starring Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray, it's ranked #38 on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 best American films of the 20th century. This 1944 Paramount Studios production was based on James M. Cain’s 1935 novella of the same name (which was based on a true story of similar events that transpired in Queens, NY in 1927). Adapted for screen by a new Hollywood talent, Ray Chandler, the movie has a fast, tight script, shadowy sets, and gorgeous 1940’s dresses.

If you haven’t seen "Double Indemnity," you are hereby instructed to check it out from your local library immediately, watch it at least twice, and then read this (and tell me what you thought below). I’m just going to discuss the actors and the time period, starting with the boisterous Edward G. Robinson. He plays a suspicious insurance claims adjuster man, MacMurray’s boss and eventual ruin. Robinson has perhaps the biggest head and least neck of any actor I can think of, and his starched collar, tight vest and ornate pocket-watch serve to accentuate the hugeness of his head, which is actually sort of its own character. Barton Keyes (Robinson) has the only brain equal to Walter Neff’s (MacMurray), and the “little man” who lives in Keyes’ conscience is a recurring theme and the undoing of Walter Neff. Here’s my favorite line Robinson delivers: “Guess I was wrong. You’re not smarter Walter, you’re just a little taller.” Besides dressing down Walter, this jab seems like a bit of personal rancor from Robinson, one of the shortest actors of 20th century.

L.A. crime stories from the 1940’s almost merit their own branch of film noir. By this point, Paramount Studios had come into its own and the quality of the lighting and film are palpably better than in the previous decade. Barbara Stanwyck, as the brilliant black widow Phyllis Dietrichson, sports a fake wig that jumps out against the dark living rooms and giant gangster cars. Stanwyck later commented about "Double Indemnity": "And for an actress, let me tell you the way those sets were lit, the house, Walter’s apartment, those dark shadows, those slices of harsh light at strange angles — all that helped my performance. The way Billy staged it and John Seitz lit it, it was all one sensational mood." Billy Wilder pioneered the slanted venetian blind shadow cast to emphasize the feeling of entrapment, which became standard fare in later film noir.

Part of what makes Stanwyck’s performance so powerful is the dichotomy between her angelic face and the sinister character beneath. Seducing Walter Neff (with lines like “only with me around, you wouldn’t have to knit...”) takes her just a day and a half. While Neff’s character changes completely in the course of the film (even in the first twenty minutes, from a nice guy in the wrong place at the wrong time to a villain) hers is consistent throughout: scheming, hard, and vicious behind a gorgeous poker face. In one of the creepiest shots of the whole movie, Walter Neff is in the back seat strangling Mr. Dietrichson (riding shotgun), as Phyllis sits cooly behind the wheel, staring at and somehow through the camera, with the same marble calm face she’s worn in every other scene.

“I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.” This line is voiced over Neff walking down a dark boulevard right after he has murdered Phyllis' husband). And despite how cliche it sounds—a man realizing he will be caught, tried and hanged for murder saying “it was the walk of a dead man” under a lonely street light—it still feels new and surprising every time I see it, it's the first moment of self- reflection after a good man has turned bad. In the last desperate meeting between Walter and Phyllis in a corner store, Phyllis’ black cat’s eye glasses against her pale skin, white blouse and blonde wig are like a dark mirror. She takes them off and says, “We got in this together, and we’re getting out together. It’s straight down line, baby,” and her expression is exactly the same as the first shot of her in the movie, where she’s standing in a towel at the top of a staircase, posed like Venus de Milo.

The last detail I’ll address is a subtle wardrobe change; throughout most of the movie, Walter wears a light fedora, vaguely matching his suit. Once Barton Keyes cracks the case and it’s all over for Walter, he wears a slumping black fedora. In his final scene with Phyllis, (“You’re the one that’s going baby, not me,”) the venetian blinds make a cage of the walls and floors, and Phyllis’ face is still a spot of light, dark lips shining. I could go on about the cinematography for pages here, so I’ll just cut it off, finishing this essay just as Barbara Stanwyck fires the fatal shot into Fred MacMurray’s chest, saying to him, “I’m rotten to the heart, just as you said,” and so honestly (I've been watching "Double Indemnity", again, while writing this). But true to film noir, he doesn’t die right away—he has time to stagger out, confess his sins, smoke two more cigarettes, and collapse in the doorway between an art deco office building and a dark Los Angeles night.