These two talks focused on storytelling, but in two very different ways.

Jim Shepard: Storytelling, World Building, and You

Jim's talks are both funny and informative.

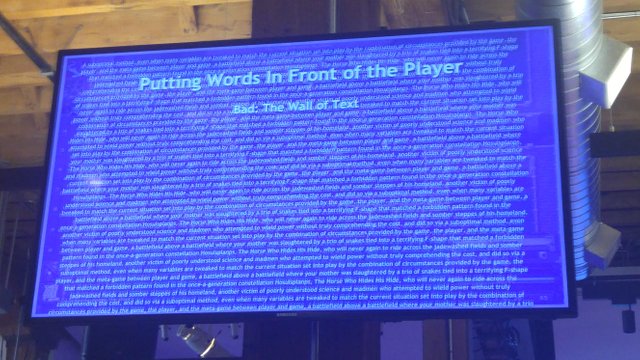

Today he was speaking on ways to convey story without the big wall of text:

This can be viewed by players as an obstacle, and it can be scary for the developer if, as Jim puts it, "you don't word good yet." Making the big wall of text an optional exercise (a book you can read at your discretion) helps a little bit, but what are ways to deliver narrative in a way that naturally fits the game?

(Jim notes that audio logs work great because they don't stop play and are sort of a "fun" discovery, but are probably too pricey for indie devs.)

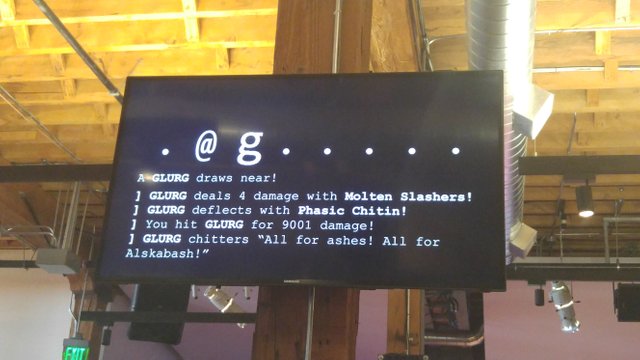

Roguelikes can show their theme and story through gameplay. Many use text for combat descriptions that introduce setting and descriptions indirectly, though something the player wants to read. Text descriptions that don't tell a story are a waste! Everybody knows what a sword is, and you may explicitly show how much damage it does. But its description can be an opportunity to "sell" the setting without a cutscene. We can even learn about the character from the way items are described to, or by, her!

Jim talked about third person descriptions and second person descriptions that are "talking from outside the game"--- a narrator, GM, or storyteller. But he suggests first-person descriptions provide the most options for expressing the character's personality, and gave some examples form Tangledeep.

His "newbie tip" for writing dialogue was to rip of some existing fictional character. It doesn't have to match the character you are writing! But having a strong sense of voice, even if it's an existing voice, can help you get started with that character's lines.

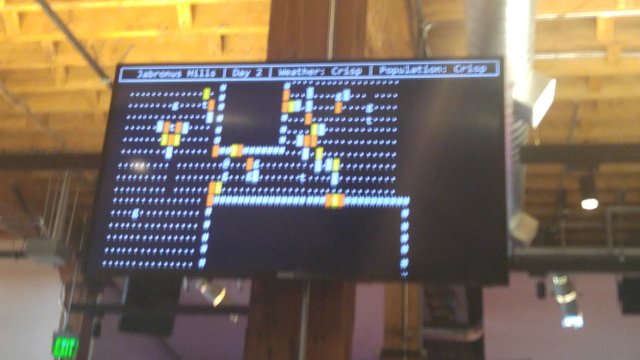

Jim closed with an example of replacing an introductory text, e.g., "the flaming glungs attacked your village leaving nothing but a ruin behind" with actually playing that introduction in the roguelike engine itself, experiencing the glung first-hand (using the combat messages to show its attributes) and seeing your village burning around your character:

Jongwoo Kim: Subjective Simulation Design: Ludonarrative Congruence in the Shrouded Isle

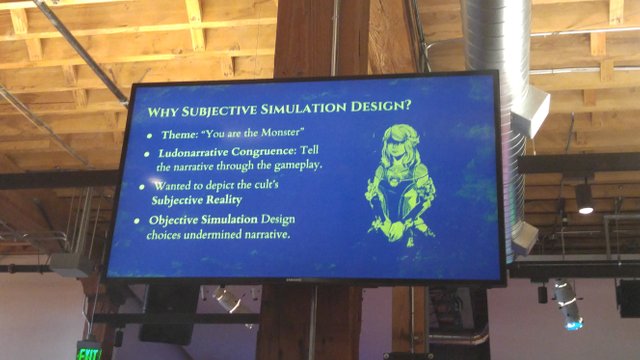

This talk about the game Shrouded Isle was about making game mechanics and game theme work together, i.e., "ludo-narrative congruence."

The game they wanted to make casts the player in the role of a cult leader in a doomed island, but they found that standard elements of play (its "ludemes") didn't fit the narrative. Management simulations tended to focus on material goods and growth, rather than "spiritual" themes and stagnation. Plus, is that really what a cult leader spends his or her time worrying about?

Instead of trying to match "objective reality", which undermines their narrative, Jongwoo and the other designers focused on "subjective simulation". He talked about three main design choices:

(1) Psychology as resources: instead of typical food/housing/ore/etc., the resources are traits of the town population: ignorance, righteousness, obedience. Because these are the resources that must be maintained to win, the designers try to motivate the player to embrace the cult's values rather than their own.

(Side note: why is this a good thing to do?)

Jongwoo characterized the resulting economy as "volatile stagnation": growth is not possible, but simple choices are given a "complex nuance." It's easier to justify large changes in psychology compared to physical resources.

(2) Character-oriented instead of process-oriented outcomes. The resources change based on the actions of single, unpredictable, individuals, so the result is humanized. Instead of ordering house X to do something, you're ordering a particular individual to do so. "Mismatched expectations creates a sense of betrayal" when you thought trusting character would be a good choice but turns out to have negative consequence.

(3) Progression via knowledge rather than advancement. A tech or upgrade tree wouldn't fit the apocalyptic theme. Instead, the player improves by increasing their knowledge of the characters they make use of in the point above. The characters' capabilities don't change, only the player's (and townspeople's) knowledge of them. This blindness to an individual's true attributes lets good intentions go wrong, encourages players to get to know the character, and rewards prudence and foresight.

I thought this was an interesting set of design choices, but I'm still dubious on the whole angle of "we wanted to make players really get into the head of their character making choices that harm the community."

Your post was upvoted by the @archdruid gaming curation team in partnership with @curie to support spreading the rewards to great content. Join the Archdruid Gaming Community at https://discord.gg/nAUkxws. Good Game, Well Played!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit