Do games have to exist solely for the benefit of the player?

Max Kreminski is a researcher in "computational creativity", games, and related topics. Their game Epitaph is an "idle game about existential risks and the death of civilizations", and a first attempt at a "gardening game".

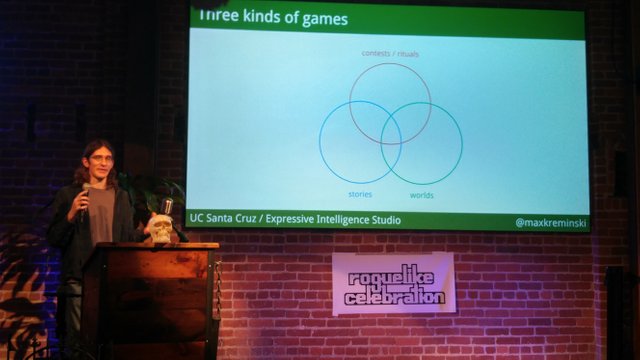

Max showed a taxonomy of games they have been thinking about: "contests and rituals" (like sports), "stories" (like a single-track RPG), and "worlds". They are most interested in the latter.

A gardening game is like Neko Atsume or SimCity. The key aspects are "nuturing" (influence but not total control) and "customization" (leaving the world better than you found it.)

Many games are solipsistic. Nothing happens if the player is not looking at it. Meg Jayanth gave a talk at GDC called "Forget Protagnoists" in which she described these as "entitlement simulators" in which everything and everyone exists for the benefit of the player. Completionism and speedrunning exhibit a "colonialist impulse" in which the player completely controls or takes over a world. The player's presence makes the world worse by extracting all the "interesting" bits and moving on. Max says this is not necessarily a bad thing in and of itself, but perhaps this has an influence on how players see the real world.

In contrast, a game like Animal Crossing encourages players to build a relationship with their world. The game keeps evolving in real time, so changes take place even in the absence of a player. (However, Max notes that even Animal Crossing is moving more in the "mining" direction; the player is the mayor and has more control, and there are some pay-to-advance features.) In constrast, the older game gives you crap about trying to cheat.

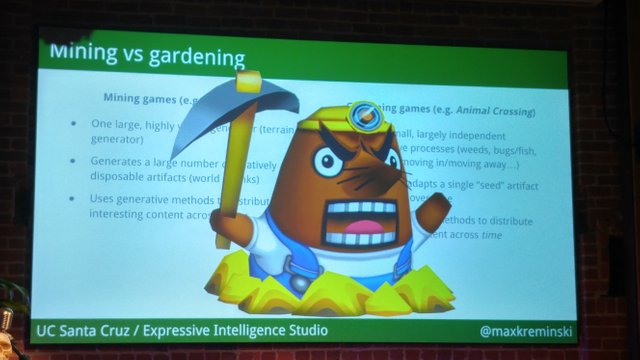

| Mining Games (like Minecraft) | Gardening Games (like Animal Crossing) |

|---|---|

| One large, highly visible generator (terrain generator) | Many small, largely independent generative processes (seeds, bugs/fish, villagers moving in/moving away) |

| Generates a large number of relatively disposable artifacts (world chunks) | Gradually adapts a single "seed" artifact (the town) over time |

| Uses generative methods to distribute interesting content across space | Uses generative methods to distribute interesting content across time |

| Generating occurs "on demand" (whenever the player "requests more content" by traveling to an area that hasn't been generated yet | Generation occurs "in time" (independent of player, based on real life calendar/clock) |

Comments

Max's talk was, like Tarn's, anticipatory rather than presenting fully-formed research. They are still trying to develop a sense for what the "genre" of gardening games are like, and how to think about such games and why they matter.

On the one hand, it seems hard to argue that games should have an existence independent of players. They are, after all, created to fulfill a human need. But, that need may not necessarily be best served by "control" or "extraction". If we continue to make virtual worlds, then the question of our obligation to them may be less abstract. Just as a human-level artificial intelligence ought to be due the respect we would give a human, we should at least consider whether an autonomous virtual world deserves some environmental care.