The repurchase agreement, or “repo,” market is an obscure but important part of the financial system that has drawn increasing attention lately. On average, $2 trillion to $4 trillion in repurchase agreements – collateralized short-term loans – are traded each day. But how does the market for repurchase agreements actually work, and what’s going on with it?

FIRST THINGS FIRST: WHAT EXACTLY IS THE REPO MARKET?

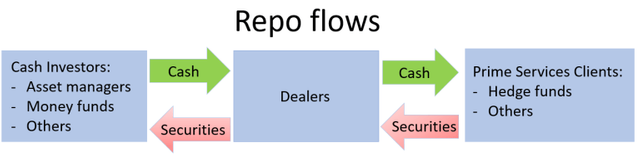

A repurchase agreement (repo) is a short-term secured loan: one party sells securities to another and agrees to repurchase those securities later at a higher price. The securities serve as collateral. The difference between the securities’ initial price and their repurchase price is the interest paid on the loan, known as the repo rate.

A reverse repurchase agreement (reverse repo) is the mirror of a repo transaction. In a reverse repo, one party purchases securities and agrees to sell them back for a positive return at a later date, often as soon as the next day. Most repos are overnight, though they can be longer.

The repo market is important for at least two reasons:

The repo market allows financial institutions that own lots of securities (e.g. banks, broker-dealers, hedge funds) to borrow cheaply and allows parties with lots of spare cash (e.g. money market mutual funds) to earn a small return on that cash without much risk, because securities, often U.S. Treasury securities, serve as collateral. Financial institutions do not want to hold cash because it is expensive—it doesn’t pay interest. For example, hedge funds hold a lot of assets but may need money to finance day-to-day trades, so they borrow from money market funds with lots of cash, which can earn a return without taking much risk.

The Federal Reserve uses repos and reverse repos to conduct monetary policy. When the Fed buys securities from a seller who agrees to repurchase them, it is injecting reserves into the financial system. Conversely, when the Fed sells securities with an agreement to repurchase, it is draining reserves from the system. Since the crisis, reverse repos have taken on new importance as a monetary policy tool. Reserves are the amount of cash banks hold – either currency in their vaults or on deposit at the Fed. The Fed sets a minimum level of reserves; anything over the minimum is called “excess reserves.” Banks can and often do lend excess reserves in the repo market.

WHAT HAPPENED IN THE REPO MARKET IN SEPTEMBER 2019?

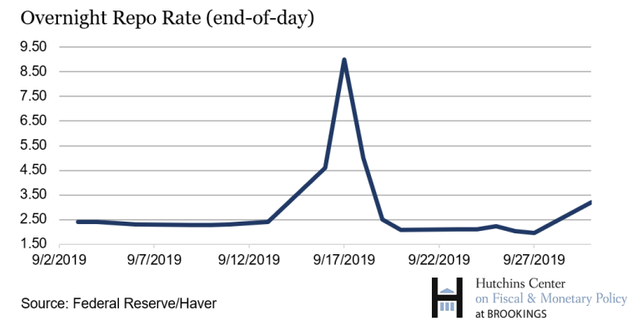

The repo rate spiked in mid-September 2019, rising to as high as 10 percent intra-day and, even then, financial institutions with excess cash refused to lend. This spike was unusual because the repo rate typically trades in line with the Federal Reserve’s benchmark federal funds rate at which banks lend reserves to each other overnight. The Fed’s target for the fed funds rate at the time was between 2 percent and 2.25 percent; volatility in the repo market pushed the effective federal funds rate above its target range to 2.30 percent.

Two events coincided in mid-September 2019 to increase the demand for cash: quarterly corporate taxes were due, and it was the settlement date for previously-auctioned Treasury securities. This resulted in a large transfer of reserves from the financial market to the government, which created a mismatch in the demand and supply for reserves. But these two anticipated developments don’t fully explain the volatility in the repo market.

Prior to the global financial crisis, the Fed operated within what’s known as a “scarce reserves” framework. Banks tried to hold just the minimum amount of reserves, borrowing in the federal funds market when they were a bit short and lending when they had a bit extra. The Fed targeted the interest rate in this market and added or drained reserves when it wanted to move the fed funds interest rates.

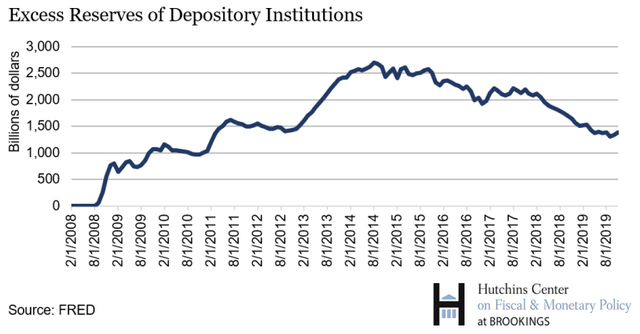

Between 2008 and 2014, the Fed engaged in Quantitative Easing (QE) to stimulate the economy. The Fed created reserves to buy securities, dramatically expanding its balance sheet and the supply of reserves in the banking system. As a result, the pre-crisis framework no longer worked, so the Fed shifted to an “ample reserves” framework with new tools – interest on excess reserves (IOER) and overnight reverse repos (ONRRP), both interest rates that the Fed sets itself – to control its key short-term interest rate. In January 2019, the Federal Open Market Committee – the Fed’s policy committee – confirmed that it “intends to continue to implement monetary policy in a regime in which an ample supply of reserves ensures that control over the level of the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates is exercised primarily through the setting of the Federal Reserve’s administered rates, and in which active management of the supply of reserves is not required.” When the Fed stopped its asset purchasing program in 2014, the supply of excess reserves in the banking system began to shrink. When the Fed started to shrink its balance sheet in 2017, reserves fell faster.

But the Fed didn’t know for sure the minimum level of reserves that were “ample,” and surveys over the past year suggested reserves wouldn’t grow scarce until they fell to less than $1.2 trillion. The Fed apparently miscalculated, in part based on banks’ responses to Fed surveys. It turned out banks wanted (or felt compelled) to hold more reserves than the Fed anticipated and were unwilling to lend those reserves in the repo market, where there were a lot of people with Treasuries who wanted to use them as collateral for cash. As demand exceeded supply, the repo rate rose sharply.

WHAT IS THE FEDERAL RESERVE DOING, AND WHY IS IT DOING THIS?

Fed officials concluded that the dysfunction in very-short-term lending markets may have resulted from allowing its balance sheet to shrink too much and responded by announcing plans to buy about $60 billion in short-term Treasury securities per month for at least six months, essentially increasing the supply of reserves in the system. The Fed has gone out of its way to say that this is not another round of quantitative easing (QE). Some in financial markets are skeptical, however, because QE eased monetary policy by expanding the balance sheet, and the new purchases have the same effect.

There are two ways in which these purchases are different from QE:

QE was designed, in part, to reduce long-term interest rates in order to encourage borrowing and economic growth and to spur more risk-taking, by driving investors into stocks and private bonds. That’s not the Fed’s intention this time. Instead, it is buying assets for the sole purpose of injecting liquidity into the banking system.

QE can have a powerful signaling effect, reinforcing the Fed’s words. By buying long-dated assets, the Fed helped persuade investors that it meant what it said about keeping rates lower for longer than might otherwise have been the case (here, here, here, and here). With its response to the repo disturbance, the Fed isn’t sending any message about where it expects to move interest rates.

The Fed has also been conducting daily and long-term repo operations. Given that short-term interest rates are closely linked, volatility in the repo market can easily spillover into the federal funds rate. The Fed can take direct action to keep the funds rate in its target range by offering its own repo trades at the Fed’s target rate. When the Fed first intervened in September 2019, it offered at least $75 billion in daily repos and $35 billion in long-term repo twice per week. Subsequently, it increased the size of its daily lending to $120 billion and lowered its long-term lending. But the Fed has signaled that it wants to wind down the intervention: Federal Reserve Vice Chair Richard Clarida said, “It may be appropriate to gradually transition away from active repo operations this year,” as the Fed increases the amount of money in the system via purchases of Treasury bills.

WHAT ELSE IS THE FED CONSIDERING?

The Fed is considering the creation of a standing repo facility, a permanent offer to lend a certain amount of cash to repo borrowers every day. It would put an effective ceiling on the short-term interest rates; no bank would borrow at a higher rate than the one they could get from the Fed directly. A new facility would “likely provide substantial assurance of control over the federal funds rate,” Fed staff told officials, whereas temporary operations would offer less precise control over short-term rates.

Yet few observers expect the Fed to start up such a facility soon. Some fundamental questions are yet to be resolved, including the rate at which the Fed would lend, which firms (besides banks and primary dealers) would be eligible to participate, and whether the use of the facility could become stigmatized.

HOW HAS THE GROWING FEDERAL DEFICIT CONTRIBUTED TO STRAINS IN THE REPO MARKET?

When the government runs a budget deficit, it borrows by issuing Treasury securities. The additional debt leaves primary dealers—Wall Street middlemen who buy the securities from the government and sell them to investors—with increasing amounts of collateral to use in the repo market.

As former Fed governor Daniel Tarullo put it at the Hutchins Center event:

“With the budget deficit having increased by about 50 percent in the last two years, the supply of new Treasuries that need to be absorbed by debt markets has grown enormously. Since these increased deficits are not the result of countercyclical policies, one can anticipate continued high supply of Treasuries, absent a significant shift in fiscal policy. In addition, the marginal purchaser of the increased supply of Treasuries has changed. Until the last couple of years, the Fed was buying Treasury bonds under its QE monetary policy. And, prior to the 2017 tax changes, U.S. multinationals with large offshore cash holdings were also significant purchasers of Treasuries. Today, though, the marginal purchaser is a primary dealer. This shift means that those purchases will likely need to be financed, at least until end investors acquire the Treasuries, and perhaps longer. It’s not surprising that the volume of Treasury-backed repo transactions has increased substantially in the last year and a half. Together, these developments suggest that digesting the increased supply of Treasuries will be a continuing challenge, with potential ramifications for both Fed balance sheet and regulatory policies.”

Furthermore, since the crisis, the Treasury has kept funds in the Treasury General Account (TGA) at the Federal Reserve rather than at private banks. As a result, when the Treasury receives payments, such as from corporate taxes, it is draining reserves from the banking system. The TGA has become more volatile since 2015, reflecting a decision by the Treasury to keep only enough cash to cover one week of outflows. This has made it harder for the Fed to estimate demand for reserves.

ARE ANY FINANCIAL REGULATIONS CONTRIBUTING TO THE PROBLEMS IN THE REPO MARKET?

The short answer is yes – but there is substantial disagreement about how big a factor this is. Banks and their lobbyists tend to say the regulations were a bigger cause of the problems than do the policymakers who put the new rules into effect after the global financial crisis of 2007-9. The intent of the rules was to make sure banks have sufficient capital and liquid assets that can be sold quickly in case they run into trouble. These rules may have led banks to hold on to reserves instead of lending them in the repo market in exchange for Treasury securities.

Among the possibilities:

Global SIFI surcharge. At the end of each year, international regulators measure the factors that make up the systemic score for a global systemically important bank (G-SIB), that in turn determines the G-SIB’s capital surcharge, the extra capital required above what other banks are required to hold. Holding a lot of reserves won’t push a bank over the threshold that triggers a higher surcharge; lending those reserves for Treasuries in the repo market could. An increase in the systemic score that pushes a bank into the next higher bucket would result in an increase in the capital surcharge of 50 basis points. So banks that are near the top of a bucket may be reluctant to jump into the repo market even when interest rates are attractive.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Bank Internal Stress Tests. The LCR requires that banks hold enough liquid assets to back short-term, runnable liabilities. Some observers have pointed to the LCR as leading to an increase in the demand for reserves. But former and current regulators point out that the LCR probably didn’t contribute to the repo market volatility because Treasury securities and reserves are treated identically for the definition of high-quality liquid assets in the regulation.

However, at the Hutchins Center event, Tarullo noted that reserves and Treasuries “are not treated as fungible in resolution planning or to meet liquidity stress tests.” As part of the post-crisis framework, banks are required to conduct their own internal liquidity stress tests, the Comprehensive Liquidity Analysis and Review (CLAR), which are subject to review by the supervisors. Banks have some preference for reserves to Treasuries because reserves can meet significant intra-day liabilities that Treasuries cannot. Banks also say that government supervisors sometimes express a preference that banks hold reserves instead of Treasuries by questioning assumptions bank make when they say they could quickly sell Treasuries without a large discount at a moment of stress.

Recovery and Resolution planning. Post-crisis rules require that banks prepare recovery and resolution plans, or living wills, to describe the institutions’ strategy for an orderly resolution if they fail. Like for the LCR, the regulations treat reserves and Treasuries as identical for meeting liquidity needs. But, similar to LCR, banks believe that government regulators prefer that banks hold on to reserves because they would not be able to seamlessly liquidate a sizeable Treasury position to keep critical functions operating during recovery or resolution.

Jamie Dimon, chairman and chief executive of J.P. Morgan Chase, points to these restrictions as an issue. In an October 2019 call with analysts, he said, “[C]ash, we believe, is required under resolution and recovery and liquidity stress testing. And therefore, we could not redeploy it into repo market, which we would’ve been happy to do. And I think it’s up to the regulators to decide they want to recalibrate the kind of liquidity they expect us to keep in that account.”

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and New York Fed President John Williams, in a letter to Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-NC), said the Fed will continue to review a wide range of factors, including supervisory expectations regarding internal liquidity stress tests. They noted that firms not subject to bank regulations, such as money market funds, government-sponsored enterprises, and pension funds, also seemed reluctant to step in when repo rates rose sharply in mid-September, suggesting that factors other than bank regulations may be important.

WHAT HAS THE FED DONE IN RESPONSE TO THE COVID-19 CRISIS?

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the Fed has vastly expanded the scope of its repo operations to funnel cash to money markets. The Fed’s facility makes cash available to the primary dealers in exchange for Treasury and other government-backed securities. Before coronavirus turmoil hit the market, the Fed was offering $100 billion in overnight repo and $20 billion in two-week repo. It ramped up the operations on March 9, offering $175 billion in overnight and $45 billion in two-week repo. Then, on March 12, the Fed announced a huge expansion. It is now on a weekly basis offering repo at much longer terms: $500 billion for one-month repo and $500 billion for three months. On March 17, at least for a time, it also greatly increased overnight repo offered. The Fed said that these liquidity operations aimed to “address highly unusual disruptions in Treasury financing markets associated with the coronavirus outbreak.” In short, the Fed is now willing to loan what is essentially an unlimited amount of money to the markets, and uptake has fallen well below amounts offered.