The Book of Ruth is the shortest of the historical books in the Bible. In most Christian canons of the Old Testament it is placed between Judges and I Samuel. In the Hebrew Tanakh it is found among the Ketuvim, or Writings, being the second of the so-called Five Megillot, or Scrolls, which also include the Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Esther. Traditionally, Ruth is ascribed to the Prophet Samuel but both its authorship and its date are open to debate. Today it is almost universally considered anonymous.

A majority of scholars date it to the Persian Period, but many still consider it to pre-date the Babylonian Exile. In the Short Chronology, the Persian Period began before the Exile, which occurred during the reign of Artaxerxes III, who was also known as Nebuchadnezzar II.

The Book of Ruth recounts the story of David’s great-grandmother Ruth and is set in the time of the Judges:

This beautiful short story revolves around the relationship between Naomi, a woman from Bethlehem, in Judah, and her Moabite daughter-in-law, Ruth. Naomi, her husband, and their two sons have come to Moab to escape from famine in Bethlehem. The first chapter recounts, in short order, the death of Naomi’s husband, the marriage of her sons to Moabite women, the sons’ deaths ten years later, and Naomi’s decision to return to Bethlehem. One daughter-in-law, Orpah, returns to her Moabite family. The other, Ruth, declares allegiance to Naomi and to the God of Israel and returns with Naomi. Despite Ruth’s company, Naomi is embittered at her many losses. In the course of the coming weeks, however, these losses are all reversed. In the second chapter, Ruth gleans in the field of Naomi’s kinsman, Boaz, and acquires enough grain to sustain Naomi and herself for some time. In the third chapter, Naomi devises a plan for Ruth’s future security: Ruth will pay a nighttime visit to the threshing floor where Boaz has been winnowing the barley harvest, and will thereby elicit a promise of marriage. The plan is successful and culminates, in chapter four, in the marriage of Ruth and Boaz and the birth of their child, Obed. The book ends with a genealogy which traces the line of Obed back to Perez, the child of Judah and Tamar (Gen. ch 38), and forward to King David. (Berlin & Brettler 1573)

In previous articles in this series I have called into question the historicity of this period. So how does this tale fit into the wider history of the Israelites?

David’s Genealogy

From an historical point of view the purpose of the Book of Ruth may simply have been to provide an introduction to the story of David—a link between the Period of the Judges (Ruth 1:1) and the birth of Israel’s greatest king (Ruth 4:22). The book concludes with a short passage—a mere five verses—in which the genealogy of David from Perez (Pharez) son of Judah is given:

Now these are the generations of Pharez: Pharez begat Hezron, And Hezron begat Ram, and Ram begat Amminadab, And Amminadab begat Nahshon, and Nahshon begat Salmon, And Salmon begat Boaz, and Boaz begat Obed, And Obed begat Jesse, and Jesse begat David. (Ruth 4:18-22)

This genealogy is repeated, with some additional details, in I Chronicles:

The sons of Pharez; Hezron, and Hamul. And the sons of Zerah; Zimri, and Ethan, and Heman, and Calcol, and Dara: five of them in all. And the sons of Carmi; Achar, the troubler of Israel, who transgressed in the thing accursed. And the sons of Ethan; Azariah. The sons also of Hezron, that were born unto him; Jerahmeel, and Ram, and Chelubai. And Ram begat Amminadab; and Amminadab begat Nahshon, prince of the children of Judah; And Nahshon begat Salma, and Salma begat Boaz, And Boaz begat Obed, and Obed begat Jesse, And Jesse begat his firstborn Eliab, and Abinadab the second, and Shimma the third, Nethaneel the fourth, Raddai the fifth, Ozem the sixth, David the seventh: Whose sisters were Zeruiah, and Abigail. (I Chronicles 2:5-16)

It is difficult to harmonize this lineage with the chronology of the other historical books of the Old Testament:

- In Numbers 1, we are told that Nahshon son of Amminadab was the leader of the Tribe of Judah at the time of the Exodus. In Numbers 2, the same man is called the captain of the children of Judah.

Between the Exodus and the birth of David, then, we must fit Salmon, Boaz, Obed and Jesse. In the traditional chronology of the Bible, the Exodus occurred more than four hundred years before the birth of David.

In Archbishop Ussher’s Annals of the World, the Fourth Age of the World begins with the Exodus in 1491 BC and ends four years after the death of David, which Ussher dated to 1016 BC. David’s birth he dated to 1085 BC:

| BCE | Event |

|---|---|

| 1491 | Exodus |

| 1085 | Birth of David |

| 1016 | Death of David |

| 1012 | Foundation of the Temple of Solomon |

In the Seder Olam Rabbah, a chronicle compiled by Jewish scholars in the second century, the Exodus took place in the year 2448 from the Creation. David’s reign in Hebron began in 2884 (Guggenheim 3, 8, 58, 133 : Johnson):

| Years from the Creation | Event |

|---|---|

| 2448 | Exodus |

| 2854 | Birth of David |

| 2884 | Beginning of David’s Reign in Hebron |

| 2924 | Death of David |

| 2928 | Foundation of the Temple of Solomon |

In each chronology, we have a gap of four hundred and six years to bridge. But according to the genealogy of David in the Book of Ruth, only five generations separate these two eras. Even if we assume that Salmon was born after the Exodus, it is impossible to bridge the gap without allotting impossibly long lifespans to David’s immediate forebears. An alternative solution is to edit the genealogy:

Ruth seems in the genealogy of David to have been his great-grandmother, but as Boaz is in the same list set down as the grandson of Nahshon, who flourished at the Exode, we are forced to suppose the omission of some nine generations, which chronologers insert according to their respective schemes. (McClintock & Strong 181)

See also Kenneth Kitchen (Kitchen 308, 357).

If, on the other hand, we accept the genealogy in Ruth as genuine and allot reasonable lifespans to David’s forebears, we arrive at a figure of approximately one century between the Exodus and the birth of David.

Biblical scholars have attempted to resolve this discrepancy by interpreting the genealogy in Ruth symbolically:

There are ten people listed in this genealogy, paralleling other such lists in Genesis. In Genesis 5, we have a genealogical list of the ten generations from Adam to Noah. Genesis 11:10-26 contains another genealogical list of ten generations, from Shem to Abraham. The first major era is from the Creation to the Flood. The next list is found after the description of the nations descended from Noah (Gen. 10) and the Tower of Babel narrative (11:1-9), when the world is divided into many languages. These two sections indicate that the world is now divided into many different groups. The genealogical list in Genesis 11 covers the period from the Flood until the birth of Abraham, patriarch of the Israelite people, the group on which the Bible will focus from this chapter onward. A list of ten generations is used to indicate a transition from one major era to another. These ten-generation epochs were understood to be significant by the rabbis as well. (Ron 85)

Earlier rabbinical scholars adopted a more literal approach:

The Midrash deals with this difficulty by explaining that certain of the ancestors of David lived extremely long lives. Based on different midrashic texts, either Obed or Jesse lived to be over 400 years old, or alternatively, Boaz, Obed and Jesse together lived for a period of over 400 years. (Ron 88)

Ron’s symbolic approach implies that several of David’s ancestors have been omitted from his lineage:

There were in fact more ancestors between Perez and David, but they were excluded from the genealogical list in order to maintain the special seven-ten symbolism. Where in this list is the ellipsis, where would the missing ancestors of King David fit in? ... The chronological problem only begins after the Exodus, so we can understand the genealogy until that point (Nahshon) to be a complete historical record. Since the birth of Obed is an integral part of the Ruth narrative, and David being the son of Jesse is integral to the narrative in Samuel I, these connections should also be viewed as literal and historical. This leaves us with only a few points on the list where we can veer from the historical to the symbolic, Nahshon to Salma, Salma to Boaz, and Obed to Jesse. It is interesting to note that other than in the genealogical lists in Ruth and I Chronicles, Boaz and Jesse are never referred to as “Boaz son of Salma” or “Jesse son of Obed.” It seems that the best candidate for the actual ellipsis point on the genealogical list is Salma, the figure who outside of these two genealogical lists is not found linked to either his father or son. (Ron 89)

I can’t say that I find any of this convincing, but Ron mentions other places in the Hebrew Bible where genealogical lists have been shortened. He concludes that Salma or Salmon stands in for several of David’s ancestors:

The Midrash also understood Salma to be a transitional figure. In Ruth Rabbah, 8:1, the Midrash asks why Salma is called Salma when he is mentioned as the son of Nahshon, but his name is changed to Salmon when he is listed as the father of Boaz. The answer given is that the name Salmon is meant to evoke the word sulam [ladder], to indicate that “up until this point it is a ladder for princes, from this point in the lineage onward it is a ladder for kings.” We can view Salma as a representative of many missing generations in the lineage, called in the Midrash the “ladder for princes” before the transitional mid-point, and the “ladder for kings” after. (Ron 91)

The Seder Olam Zutta, an anonymous rabbinical chronicle from the early 9th century, passes over the period of the Judges entirely, describing David’s reign immediately after recording the death of Joshua. But it does separate these two events by almost four centuries.

Boaz gave birth to Obed. And Obed begat Yishai [Jesse]. Yishai begat David. And David reigned over Israel in the 390th year of their entry into the land [of Canaan]. This was the 430th year from the Exodus. (Seder Olam Zutta 5 : Génébrard 12)

The Mother of Obed

The Book of Ruth recounts how Ruth, a Moabite, becomes the mother of David’s grandfather Obed. But there is a puzzling passage in the final chapter:

So Boaz took Ruth, and she was his wife: and when he went in unto her, the Lord gave her conception, and she bare a son. And the women said unto Naomi, Blessed be the Lord, which hath not left thee this day without a kinsman, that his name may be famous in Israel. And he shall be unto thee a restorer of thy life, and a nourisher of thine old age: for thy daughter in law, which loveth thee, which is better to thee than seven sons, hath born him. And Naomi took the child, and laid it in her bosom, and became nurse unto it. And the women her neighbours gave it a name, saying, There is a son born to Naomi; and they called his name Obed: he is the father of Jesse, the father of David. (Ruth 4:13-17)

There is a son born to Naomi. Is this a vestige of another version of the story, one in which Naomi is the biological mother of Obed? Over the centuries this discrepancy has been interpreted in various ways, but I shall not pursue the matter here.

Conclusion

The discrepancies between these different chronologies do not dispose us to trust any of them.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Second Edition, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Gilbert Génébrard, Hebraeorum Breve Chronicon, Martinus Iuvenis, Paris (1572)

- Heinrich W Guggenheimer (translator & commentator), Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland (2005)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam, Xulon Press, Camarillo, CA (2006)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan (2003)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 9, Harper & Brothers, New York (1889)

- Zvi Ron, The Genealogical List in the Book of Ruth: A Symbolic Approach, Jewish Bible Quarterly, Volume 38, Number 2, Pages 85-92, Jewish Bible Association, Jerusalem (2010)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Ruth and Boaz: Kazimierz Alchimowicz (artist), Booz and Ruth Collecting Barley Ears, Private Collection, Public Domain

- Ruth and Naomi: Philip Hermogenes Calderon (artist), Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, Public Domain

- The Anointing of David: Paolo Veronese (artist), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Yelkrokoyade (photographer), Public Domain

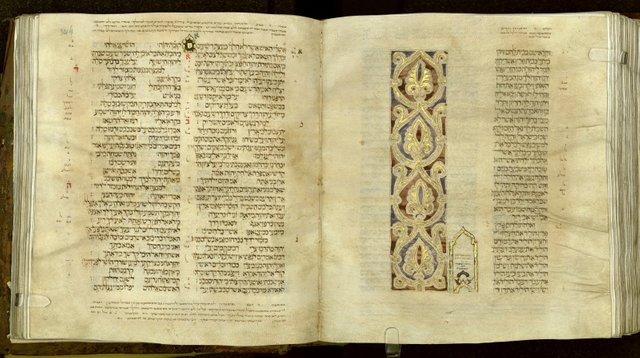

- Keter Damascus (Ruth 4 and Psalms 1): The Keter Damascus Bible, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Public Domain

- Rabbi Zvi Ron: © Yeshivat Netiv Aryeh, Fair Use

- Ruth, Naomi & Obed: The Book of Ruth, Simeon Solomon (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain