In the Deuteronomistic History of Israel Saul was the first King of Israel. Anointed by the Prophet Samuel, he reigned at a time of conflict with the Philistines. His story is told in the First Book of Samuel (I Samuel 9-31). Briefly, he was the son of Kish of the Tribe of Benjamin : he reigned in Gibeah : he died fighting the Philistines at the Battle of Mount Gilboa : and he was buried in Zelah. Three of his sons—Jonathan, Abinadab, and Malchishua—died with him at Mount Gilboa. His surviving son, Ish-bosheth, succeeded him as King of Israel, but his accession was contested by David, who ultimately prevailed and became King in his stead.

But was Saul an historical character? In the last article we saw that there were very good reasons to doubt the accuracy of the Deuteronomistic History. The Philistines, who are portrayed as the implacable enemies of Israel during the reigns of Saul and David, probably only settled in Canaan in the early Persian Period. In the Short Chronology this was after the 18th Dynasty of Egypt had come and gone, and when the 19th Dynasty was drawing to a close. This calls into question the whole history of the United Monarchy.

Saul’s historicity is also undermined by the numerous discrepancies that exist between the various sources:

The circumstances of Saul’s career are too well known to require recapitulation. It will be sufficient to refer to some of the recognized difficulties of the narrative. These difficulties arise from the fact that we appear to have two distinct biographies of Saul in the present Books of S[amuel]. (Orr 2697-2698)

Saul’s Genealogy

Saul’s lineage is first given in I Samuel 9:

Now there was a man of Benjamin, whose name was Kish, the son of Abiel, the son of Zeror, the son of Bechorath, the son of Aphiah, a Benjamite, a mighty man of power. And he had a son, whose name was Saul, a choice young man, and a goodly: and there was not among the children of Israel a goodlier person than he: from his shoulders and upward he was higher than any of the people. (I Samuel 9:1-2)

We are also told in the following chapter that Saul belonged to the Clan of Matri, the Matrites, who are otherwise unknown:

And when Samuel had caused all the tribes of Israel to come near, the tribe of Benjamin was taken. When he had caused the tribe of Benjamin to come near by their families, the family of Matri was taken, and Saul the son of Kish was taken. (I Samuel 10:20-21)

In I Chronicles 8, however, Saul is given a different genealogy:

Now Benjamin begat Bela his firstborn, Ashbel the second, and Aharah the third, Nohah the fourth, and Rapha the fifth. And the sons of Bela were, Addar, and Gera, and Abihud, And Abishua, and Naaman, and Ahoah, And Gera, and Shephuphan, and Huram ...

And at Gibeon dwelt the father of Gibeon; whose wife’s name was Maachah: And his firstborn son Abdon, and Zur, and Kish, and Baal, and Nadab, And Gedor, and Ahio, and Zacher. And Mikloth begat Shimeah. And these also dwelt with their brethren in Jerusalem, over against them. And Ner begat Kish, and Kish begat Saul, and Saul begat Jonathan, and Malchishua, and Abinadab, and Eshbaal. (I Chronicles 8:1-5 ... 29-33))

This passage is obviously corrupt. Bela’s son Gera is mentioned twice, and we are not told who the father of Gibeon was or who begot Ner the father of Kish. In the very next chapter, however, some of these errors are corrected:

And in Gibeon dwelt the father of Gibeon, Jehiel, whose wife’s name was Maachah: And his firstborn son Abdon, then Zur, and Kish, and Baal, and Ner, and Nadab. And Gedor, and Ahio, and Zechariah, and Mikloth. And Mikloth begat Shimeam. And they also dwelt with their brethren at Jerusalem, over against their brethren. And Ner begat Kish; and Kish begat Saul; and Saul begat Jonathan, and Malchishua, and Abinadab, and Eshbaal. (I Chronicles 9:35-39)

Who was the father of Kish: Abiel or Ner? And is Eshbaal the same as Ish-bosheth? And if Jehiel was the father of Gibeon, why is Gibeon not listed among his many sons? Some scholars have speculated that the father of Gibeon must mean the founder of Gibeah, as he dwelt in Gibeon (McClintock & Strong 373).

There is also some confusion over the relationship between Ner and Kish. Was Ner Kish’s brother (I Samuel 14:51) or his father (I Chronicles 8:33, 9:39)? There are also discrepancies between the various lists of Saul’s descendants. See McClintock & Strong 372 for further details.

Later rabbinical scholars attempted to clarify the situation by providing a complete genealogy from Benjamin to Saul, and from Saul to Mordechai, one of the principal characters in the Book of Esther, and allegedly a descendant of Saul. The latter part of this genealogy agrees for the most part with I Samuel 9, though some of the Hebrew names are transcribed differently in the following translation, which was carried out by ImTranslator:

And it is accepted for the people, and his name is Mordechai ben Yair ben Shemei ben Kish, and that he was the son of Kish and there were not many generations between them, for he says ben Yair ben Shemei ben Bana ben Moza ben Elah ben Mefibsheth ben Jonathan ben Shaul ben Kish ben Aviel ben Tzarur ben Bakurat ben Afich ben Shechariah ben Azariah ben Shokk ben Michael ben Eliel ben Amihud ben Shephatiah ben Pethuel ben Pithon ben Meluch ben Jerubael ben Hananiah ben Zebedee ben Shemaria ben Zechariah ben Marimoth ben Husham ben Shehariah ben Atkephon ben Azariah ben Gera ben Bala ben Benjamin ben Jacob. (Yalkut Shimoni on Nach 1053:5)

The genealogy is I Samuel 9 may be a literary device:

The genealogy for Saul in 1 Sam 9:1 probably represents a use of the motif of the seven-generation pedigree as a literary device to emphasize Saul’s destiny to greatness from birth ... Apparently only six generations of names from Saul’s family were known, forcing the author to include an unnamed “Yimnite man” [ie a Benjaminite] as Aphiah’s father and the founding generation to enable him to employ the literary device. (Freedman 502)

It has even be hypothesized that Saul was not a Benjaminite but an Asherite:

The MT [Masoretic Text] and LXX [Septuagint] both describe Aphiah as “the son of a Yim (i)nite man.” The LXX offers a variant reading, “a Yim (i)nite man,” which would appear to indicate Aphiah’s own clan affiliation instead of that of his father, and which loses the seventh generation from the genealogy. Since the opening phrase in the verse describes Kish as a Benjaminite, there is no need to repeat the Benjaminite affiliation of the founding ancestor, and the Hebrew text does not read “Benjaminite” for Aphiah’s father, but merely “Yiminite.”

It appears that the founder of the Saulide family is not to be associated with the tribe of Benjamin, which is the common presumption ... but rather with the neighboring Asherite clan of Yimnah (1 Chr 7:35), probably located in southeastern Mt. Ephraim in the vicinity of Bethel ... (Freedman 502)

The irreconcilable differences between these various genealogies cast doubt on all of them.

How Saul Became King

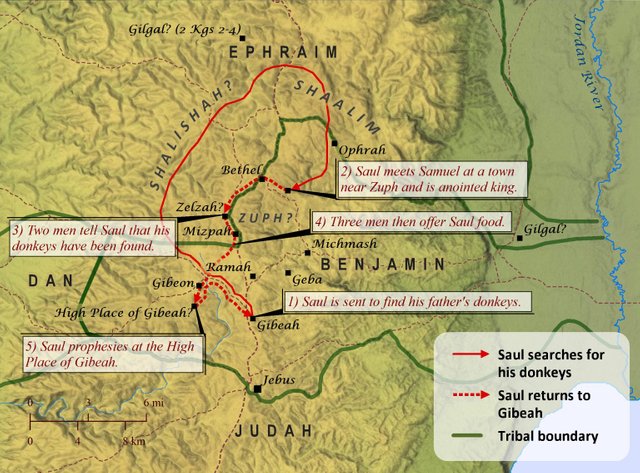

Another discrepancy in the life of Saul concerns the manner in which he came to be anointed by Samuel as Israel’s first King. In I Samuel 9, we read the following curious tale:

And the asses of Kish Saul’s father were lost. And Kish said to Saul his son, Take now one of the servants with thee, and arise, go seek the asses. And he passed through mount Ephraim, and passed through the land of Shalisha, but they found them not: then they passed through the land of Shalim, and there they were not: and he passed through the land of the Benjamites, but they found them not. And when they were come to the land of Zuph, Saul said to his servant that was with him, Come, and let us return; lest my father leave caring for the asses, and take thought for us. And he said unto him, Behold now, there is in this city a man of God, and he is an honourable man; all that he saith cometh surely to pass: now let us go thither; peradventure he can shew us our way that we should go ...

So they went unto the city where the man of God was ... And they went up into the city: and when they were come into the city, behold, Samuel came out against them, for to go up to the high place. Now the Lord had told Samuel in his ear a day before Saul came, saying, To morrow about this time I will send thee a man out of the land of Benjamin, and thou shalt anoint him to be captain over my people Israel, that he may save my people out of the hand of the Philistines: for I have looked upon my people, because their cry is come unto me. And when Samuel saw Saul, the Lord said unto him, Behold the man whom I spake to thee of! this same shall reign over my people ... Then Samuel took a vial of oil, and poured it upon his head, and kissed him, and said, Is it not because the Lord hath anointed thee to be captain over his inheritance? (I Samuel 9:3-10:1)

In the tenth chapter, however, a very different story is told. Now Saul is chosen by lot:

And Samuel called the people together unto the Lord to Mizpeh; And said unto the children of Israel, Thus saith the Lord God of Israel, I brought up Israel out of Egypt, and delivered you out of the hand of the Egyptians, and out of the hand of all kingdoms, and of them that oppressed you: And ye have this day rejected your God, who himself saved you out of all your adversities and your tribulations; and ye have said unto him, Nay, but set a king over us. Now therefore present yourselves before the Lord by your tribes, and by your thousands.

And when Samuel had caused all the tribes of Israel to come near, the tribe of Benjamin was taken. When he had caused the tribe of Benjamin to come near by their families, the family of Matri was taken, and Saul the son of Kish was taken: and when they sought him, he could not be found. Therefore they enquired of the Lord further, if the man should yet come thither. And the Lord answered, Behold he hath hid himself among the stuff. And they ran and fetched him thence: and when he stood among the people, he was higher than any of the people from his shoulders and upward. And Samuel said to all the people, See ye him whom the Lord hath chosen, that there is none like him among all the people? And all the people shouted, and said, God save the king. (I Samuel 10:17-24)

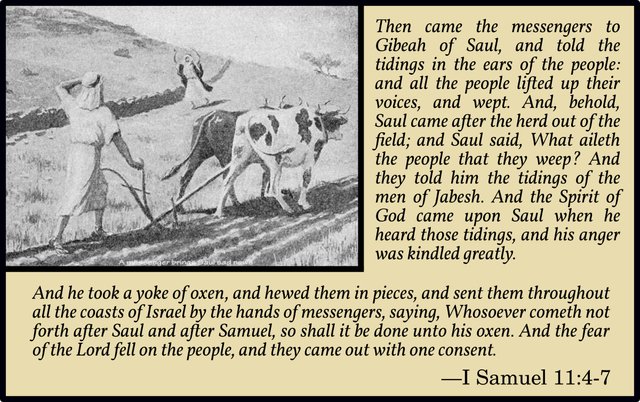

A third account of the anointing of Saul is recounted in I Samuel 11. Now Saul earns the kingship on the battlefield:

Then Nahash the Ammonite came up, and encamped against Jabeshgilead: and all the men of Jabesh said unto Nahash, Make a covenant with us, and we will serve thee. And Nahash the Ammonite answered them, On this condition will I make a covenant with you, that I may thrust out all your right eyes, and lay it for a reproach upon all Israel ... Then came the messengers to Gibeah of Saul, and told the tidings in the ears of the people: and all the people lifted up their voices, and wept. And, behold, Saul came after the herd out of the field; and Saul said, What aileth the people that they weep? And they told him the tidings of the men of Jabesh. And the Spirit of God came upon Saul when he heard those tidings, and his anger was kindled greatly ...

And it was so on the morrow, that Saul put the people in three companies; and they came into the midst of the host in the morning watch, and slew the Ammonites until the heat of the day: and it came to pass, that they which remained were scattered, so that two of them were not left together. And the people said unto Samuel, Who is he that said, Shall Saul reign over us? bring the men, that we may put them to death. And Saul said, There shall not a man be put to death this day: for to day the Lord hath wrought salvation in Israel. Then said Samuel to the people, Come, and let us go to Gilgal, and renew the kingdom there. And all the people went to Gilgal; and there they made Saul king before the Lord in Gilgal; and there they sacrificed sacrifices of peace offerings before the Lord; and there Saul and all the men of Israel rejoiced greatly. (I Samuel 11)

Once again we find irreconcilable differences between the sources, which tempts us to doubt all of them.

The Length of Saul’s Reign

The length of Saul’s reign is still a matter of debate. The relevant verse, I Samuel 13:1, is corrupt in the Hebrew Tanakh and lacking in the Greek Septuagint:

Saul was ... years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel two years. (Berlin & Brettler)

A son of a year [is] Saul in his reigning, yea, two years he hath reigned over Israel, (Young’s Literal Translation)

Over the centuries scholars have interpreted this verse in every conceivable manner:

The number is lacking in the Heb. text; also, the precise context of the “two years” is uncertain. The verse is lacking in the Septuagint. (Berlin & Brettler 583 fn a)

This verse literally translated is, “Saul was one year old when he began to reign, and he reigned two years over Israel.” In its form it exactly follows the usual statement prefixed to each king’s reign, of his age at his accession, and the years of his kingdom ... As regards the length of Saul’s reign, St. Paul makes it forty years (Acts 13:21), exactly the same as that of David (1 Kings 2:11) and of Solomon (1 Kings 11:42); and Josephus testifies that such was the traditional belief of the Jews (‛Antiq.,’ 6:14, 9). On the other hand, it is remarkable that the word here for years is that used where the whole number is less than ten. The events, however, recorded in the rest of the book seem to require a longer period than ten years for the duration of Saul’s reign; thirty-two would be a more probable number, and, added to the seven and a half years’ reign of Ishbosheth (see 2 Samuel 5:5), they would make up the whole sum of forty years ascribed by St. Paul to Saul’s dynasty. It is quite possible, however, that these forty years may even include the fifteen or sixteen years of Samuel’s judgeship. But the two facts, that all the three sons of Saul mentioned in 1 Samuel 14:49 were old enough to go with him to the battle of Mount Gilboa, where they were slain; and that Ishbosheth, his successor, was forty years of age when his father died, effectually dispose of the idea that Saul’s was a very short reign. (Spence & Exell 226)

Heb. the son of one year in his reigning ... Verse 1. Saul reigned one year] A great deal of learned labour has been employed and lost on this verse, to reconcile it with propriety and common sense. I shall not recount the meanings put on it. I think this clause belongs to the preceding chapter, either as a part of the whole, or a chronological note added afterwards; as if the writer had said, These things (related in chap, xii.) took place in the first year of Saul’s reign : and then he proceeds in the next place to tell us what took place in the second year, the two most remarkable years of Saul’s reign. In the first he is appointed, anointed, and twice confirmed, viz., at Mizpeh and at Gilgal; in the second, Israel is brought into the lowest state of degradation by the Philistines, Saul acts unconstitutionally, and is rejected from being king. These things were worthy of an especial chronological note. (Clarke 247)

The only possible literal translation of the Hebrew of this verse is, “Saul was the son of one year (i.e., one year old); he began to reign, &c.” In several places in the Books of Samuel the numbers are quite untrustworthy (we have another instance of this in the 5th verse of this chapter). The present verse, however, is an old difficulty, the corruption or gap in the text dating from a far back period. The English translation is simply a probable, but conjectural, paraphrase. (Ellicott 343)

The text of this verse, omitted by the Septuagint, is held to be corrupt, and the numerals denoting Saul’s age at his accession as well as the duration of his reign, are thought to be omitted or faulty. Saul may have been about 30 at his accession, and have reigned some 32 years, since we know that his grandson Mephibosheth was five years old at Saul’s death 2 Samuel 4:4; and 32 added to the seven and a half years between the death of Saul and that of Ishbosheth, makes up the 40 years assigned to Saul’s dynasty in Acts 13:21. (Albert Barnes, Notes on the Whole Bible)

Saul reigned one year ... “Or the son of a year in his reigning” (s); various are the senses given of these words: some interpret them, Saul had a son of a year old when he began to reign, Ishbosheth, and who was forty years of age when his father died, 2 Samuel 2:10, (John Gill, Exposition of the Whole Bible)

These were the principal transactions that occurred during the first decade of Saul’s reign (which we venture to assign as the meaning of the first clause of ch. 13 — “the son of a year was Saul in his reigning;” the emendation of Origen, “Saul was thirty years old,” being required by the chronology, for he seems, at the next event, to have been forty years old); and the subsequent events happened in the second decade, which may be the meaning of the latter clause ... In the twentieth year of his reign (as the age of Jonathan evidently requires; the text being corrupt ... (McClintock & Strong 374)

The rabbinical chronologists who compiled the Seder Olam Rabbah only assigned three years to Saul’s reign:

The statement that the Ark was at Qiryat Yearim for 20 years is the linchpin for the chronology of the entire period between the destruction of Shiloh and the reign of David. David brought the ark to Jerusalem at the beginning of his reign there. He was king at Hebron for 7 years, this leaves only 13 years for the judgeship of Samuel and the kingship of Saul. Scripture, quoted in the next passage, gives Saul 3 years; hence, Samuel was judge for 10 years. Most European manuscripts give here 11 years to Samuel and only two years to Saul. This is the Yerushalmi tradition of interpretation of I Sam. 13:1: “One year was Saul at his reign and two years he ruled over Israel.” However, the Babylonian Talmud and Seder ‛Olam take this to mean that for one year he shared the rule with Samuel and two years he was king in his own right; this leaves 10 years for Samuel. (Guggenheim 130)

Once again we find that the life of Saul is beset with irreconcilable differences.

These are just some of the discrepancies between the divergent narratives. There are others. For example, the manner in which David was introduced to Saul:

[I Samuel] Ch. xvi.-xviii. contain two documents descriptive of David’s introduction to Saul. In the first. Samuel goes to Bethlehem to offer sacrifices and anoint the future king of Israel. After he has passed, by tain YHWH’s order, upon all the sons of Jesse that are present, the youngest one, David, who, caring for his sheep, is absent from the sacrifice, is called in and formally anointed (xvi. 1-13). After this act “the Spirit of YHWH came mightily upon” him “from that day forward.” The character of David as a shepherd boy is developed in xvii. 1-xviii. 5, where David chances to visit his brothers during a battle with the Philistines, and with a shepherd’s sling slays Goliath, and wins the encomiums of the people of Israel. The second account (xvi. 14-23) introduces David as a skilful musician, “a mighty man of valor, and a man of war, and prudent in speech” (ib. verse 18). Saul is so impressed by him that he makes him his armor-bearer and holds him in high esteem. If the accounts are not separate in origin, it is not clear how Saul could have asked the question attributed to him in xvii. 55-58. Subsequent references (xix. 5; xxi. 9, etc.) to David’s victory over Goliath show how this event was woven in with the traditions of his early life. (Singer 77)

There are also duplicate accounts of David’s merciful treatment of Saul in I Samuel 24 (Singer 77-78). Saul’s death is also recounted twice:

It is asserted that there are two accounts of Saul’s death. In one it is stated that he was defeated, his sons were slain, and he himself was wounded. To escape the ignominy of falling alive into the hands of the enemy he urged his armor-bearer to slay him. Upon the attendant’s refusal to do so, he fell upon his own sword. According to the other account an Amalekite slew him. These two records are doubtless built upon the fact that Saul and his sons died on the field of battle fighting for the liberty of their people. (Singer 78)

Archaeology

Is there any archaeological evidence for the reign of Saul? His capital, Gibeah, has been identified with Tell el-Ful, an archaeological mound about 5 km north of Jerusalem, though this has been questioned by some scholars. Tell el-Ful has been the subject of several excavations:

1868: Excavated by Charles Warren

1874: Described by Claude Reignier Conder

1922-23: Excavated by William Foxwell Albright

1964: Excavated by Paul and Nancy Lapp

Most notable among the discoveries were the remains of a fortress:

Saul’s capital, once he had assumed his kingship, this place is now conceded to have been at Tell el-Ful, a few miles north of Jerusalem, on an isolated, defensible bluff overlooking the main road north and south of it. Upon this strategic point was found an Iron I occupation replaced (at an interval) by a fortress (“I”), subsequently refurbished (“II”), and then later in disuse. The oldest level may reflect the Gibeah of Judg. 19-20. The excavations by Albright, checked by Lapp, would favor the view that it was Saul who built the first fortress, later repaired by him or David. (Kitchen 97)

Scottish Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen believes that the United Monarchy belongs to the early part of the Iron Age, so he takes solace from these discoveries. In the model of the Short Chronology to which I subscribe, however, any historical Saul must be sought in the Late Bronze Age. No remains from this period have been unearthed at Tell el-Ful:

The pottery from the first fortress belongs to the same ceramic period as that from the second, from which it cannot be easily distinguished, so a full discussion of it will be reserved for the next section. The few potsherds which were found in situ below the burnt level were in general coarser, with more limestone particles, and were often indistinguishable from Bronze Age sherds. Such few rims, handles, and bottoms as appeared belonged to the Iron Age types, however. Not a single clear Bronze Age type appeared in all our work on Tell el-Ful. It is, therefore, impossible to regard Gibeah I as a pre-Israelite stage of culture, and the ascription to the period of the Judges (for which see Chapters IV and V) seems certain. Our fortress was, accordingly, built toward the end of the thirteenth century B. C., and burned near the end of the twelfth. (Albright 8)

In William F Albright’s chronology, the end of the thirteenth century corresponds to the latter part of the 19th Dynasty of Egypt. In the Short Chronology, this brings us down to the early Persian Period. This is much too late for an historical Saul.

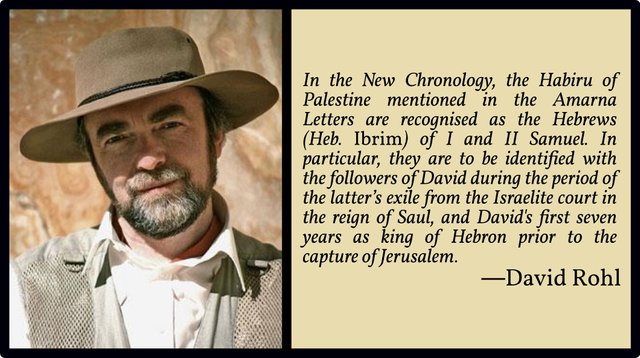

David Rohl and Labayu

Before leaving the archaeological question of Saul’s historicity, I would like to briefly examine the views of another revisionist, David Rohl. Inspired by the researches of Immanuel Velikovsky, this British Egyptologist has devised an independent chronology of the Ancient World, to which he has given the name the New Chronology. In this timeline the period of Israelite history covered by I Samuel corresponds to the Amarna Period of Egyptian history—the reign of Amenhotep IV, or Akhenaten, towards the end of the 18th Dynasty.

Rohl has equated several of the characters mentioned in the El-Amarna Letters with well-known figures mentioned in the Bible:

- Labaya, or Labayu, is Saul.

- Mutbaal is Saul’s son Eshbaal (Ish-Bosheth).

- Benenima is Baanah, one of Ish-Bosheth’s military chiefs.

- Dadua is David.

- Yishuya is David’s father Jesse

- Ayab is David’s general Joab.

- The Habiru are the Hebrews (Israelites).

- Aziru is Hadadezer, King of Zobah during David’s reign.

- Gulatu is the same as the Biblical name Goliath.

In the Short Chronology the Amarna Period corresponds to the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah, as described in the Bible in I and II Kings (and I and II Chronicles), so Rohl’s identifications must be rejected. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that he has found several intriguing coincidences between the proper names in these two sources. When we come to discuss the Amarna Period, will we be able to find more convincing identifications for these characters?

Other Sauls

The name Saul is generally interpreted as the passive participle of the Hebrew verb , to ask. Hence the name means asked (Strong 111 : Orr 2697). This is a rather convenient name for the man who was called upon by the Israelites to be their king. Is this another hint that Saul was not an historical figure?

There are three other characters in the Hebrew Bible with the same name, though this is sometimes transcribed into English as Shaul. The first of these is one of the rulers of Edom, the descendants of Isaac’s son Esau, who are listed in Genesis 36:

And Samlah died, and Saul of Rehoboth by the river reigned in his stead. And Saul died, and Baalhanan the son of Achbor reigned in his stead. (Genesis 36:37-38 : I Chronicles 1:48-49)

Another Shaul is listed among the sons of Simeon. He is the ancestor of the Shaulites:

And the sons of Simeon; Jemuel, and Jamin, and Ohad, and Jachin, and Zohar, and Shaul the son of a Canaanitish woman. (Genesis 46:10 : Exodus 6:15 : Numbers 26:13 : I Chronicles 4:24)

The third Shaul is a son of Uzziah and a member of the Kohathites of the Tribe of Levi:

The sons of Levi; Gershom, Kohath, and Merari ... And the sons of Kohath were, Amram, and Izhar, and Hebron, and Uzziel ... The sons of Kohath; Amminadab his son, Korah his son, Assir his son, Elkanah his son, and Ebiasaph his son, and Assir his son, Tahath his son, Uriel his son, Uzziah his son, and Shaul his son. (I Chronicles 6:16-24)

We can at least conclude that the name Saul was not coined afresh to designate the first King of Israel. It was a traditional name with a long history.

Conclusion

There are very good reasons to doubt the historicity of the Biblical King Saul.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- William Foxwell Albright, Excavations and Results at Tell el-Fûl (Gibeah of Saul), The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Volume 4, The American Schools of Oriental Research, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut (1924)

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible ... With a Commentary and Critical Notes, Volume 2, G Lane & P P Sandford, New York (1843)

- Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- Heinrich W Guggenheimer (translator & commentator), Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland (2005)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- Nancy C Lapp, The Third Campaign at Tell el-Fûl: The Excavations of 1964, The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Volume 45, The American Schools of Oriental Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1978)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 9, Harper & Brothers, New York (1880)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 4, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- David Rohl, Pharaohs and Kings: A Biblical Quest [A Test of Time: The Bible from Myth to History], Crown Publishers, Inc, New York (1995)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 11, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1905)

- Henry Donald Maurice Spence & Joseph Samuel Exell, The Pulpit Commentary, Volume 4, Ruth, I and II Samuel, Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, Massachusetts (1980)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Samuel Anointing Saul: François de Nomé (artist), Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Public Domain

- Saul and the Witch of Endor: Matthias Stom (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- Saul: Jozef Israëls (artist), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Public Domain

- King Saul under the Influence of an Evil Spirit: William Wetmore Story (sculptor), North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina, Public Domain

- Saul in Search of His Father’s Asses: © David P Barrett (designer), Creative Commons License

- Saul is Anointed by Samuel: The Winchester Bible, Winchester Cathedral, Public Domain

- Saul Learns of the Ammonite Threat: © StudyJesus.com, Fair Use

- David and Saul: Ernst Josephson (artist), Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Michael Philip (photographer), Public Domain

- Albert Barnes: James Neagle (artist), John Sartain (engraver), Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Public Domain

- David Spares the Life of Saul: Pietro Antonio Magatti (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- The Death of Saul: Elie Marcuse (artist), Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Public Domain

- Tell el-Ful (Gibeah): © Ferrell Jenkins (photographer), Fair Use

- David Rohl: © David Rohl, Fair Use

- David Presents the Head of Goliath to King Saul: Rembrandt van Rijn (artist), Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland, Public Domain

Online Resources