Joseph Juste Scaliger worked on his Thesaurus Temporum from 1599 until 1606. These years were not free from the usual polemics and academic scandals that Scaliger seemed to thrive on:

Work continued for years, intermittently. So did interruptions, as bumptious Puritans and furious Catholics denounced Scaliger and needed to be denounced in their turn―sometimes in full-scale works that could not fit inside even the expanded plan. To be sure, at least one of these apparent interruptions to Scaliger’s studies actually led him to revise a major set of his early theories, drawing on knowledge, skills, and books that Leiden had made available to him. In doing so, he recast his views of Jewish history in ways that would have a massive impact on his big chronology. ―Grafton 507

The controversy Grafton is referring to is one that most scholars today would find trivial and inconsequential. It revolved around the identity of the Hasidim, a Jewish group of the Intertestamental Period. The Protestant Hebraist Johannes Drusius believed that this term referred to the Pharisees, but the Jesuit scholar Nicolaus Serarius argued that the Hasidim were Essenes. Serarius followed Scaliger in deriving the name Essene from the Syriac [Middle Aramaic] word chasi (holy). Drusius replied to Serarius in 1603. The following year Drusius’ response was published in Frankfurt.

Scaliger could not resist entering the lists against a Jesuit in defence of a fellow Protestant:

‛This is all I know: in the points on which he criticizes us, he is dishonest; in Greek he is childish; in Hebrew he is a baby; in the history of these [Jewish] sects he shows no judgement; and in his manner of addressing his superiors he shows no shame.’ ―Grafton 508

Scaliger’s response to Serarius, Elenchus trihaeresii Nicolai Serarii [A Refutation of “The Three Sects” of Nicolaus Serarius], was published in the Dutch city of Franeker in 1605. Scaliger found himself in the unusual position of having to refute a scholar who cited earlier works of Scaliger himself in support of his thesis. There was only one course of action left open to him, one that was virtually unprecedented: Scaliger had to admit that he had been in error:

Again he found himself used against his friend and co-religionist; but now he had changed his mind decisively.

In the first place, Scaliger had now extended and elaborated his beliefs about the Hellenistic Jewish culture to which Philo belonged. In the first De emendatione he had used Philo as a powerful witness against the derivative and foolish Eusebius. In the second edition he argued that Philo, like other Hellenistic Jews, had used the Greek language and Bible in synagogue service. He had in fact known no Hebrew. Now he drew a new inference: Philo had no authority at all as a witness on Semitic languages and Hebrew traditions. ―Grafton 509

Scaliger was forced to abandon his Syriac theory on the etymology of the name Essene:

[Serarius says:] Philo’s words are: ‛In my opinion they are called Essenes, though not quite in accord with the form of the Greek language, because of their holiness.’ ‛By these words’, Serarius says, ‛he explicitly states out that this derivation is not drawn from a Greek word.’ This I certainly believed, and I persuaded Serarius of it, though, as in other matters, he conceals that. Therefore I was forced to derive its origin from Syriac ... But I confess my error, and I willingly pay the penalty for believing Philo, who spoke only Greek, and was so ignorant of Hebrew that I doubt if he even knew how to read the language. In short, Philo could not derive this word from Hebrew or Syriac, since he was more ignorant of both languages than any Gaul or Scyth. All his writings clearly attest to this. ―Grafton 509, translating from Scaliger’s Elenchus

Scaliger came to believe that there had been two sects of Jews in Hellenistic times:

He now argued that even before the time of the Hasmonaeans there had been two sorts of Jews, one that accepted the Law alone and one that accepted traditions as well. The former had given rise to the Karaites, and these to the Sadducees; the latter had given rise to the Hasidim, members of religious guilds who voluntarily carried out observances that the law did not require, and they in turn produced the Pharisees of the time of Jesus. ―Grafton 511–512

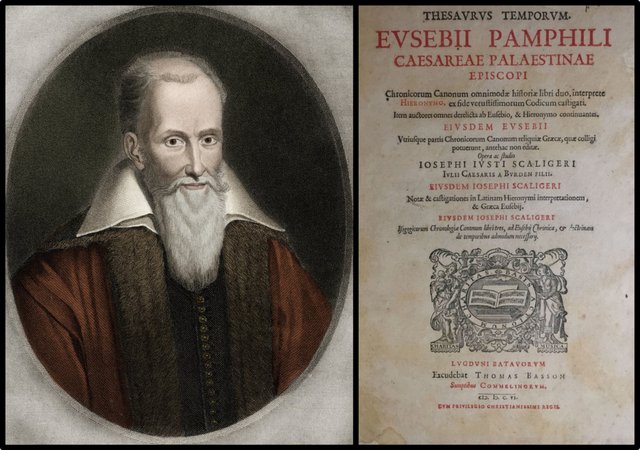

The Thesaurus Temporum

While this controversy was simmering Scaliger continued to work on his monumental Thesaurus Temporum. Between 1603 and 1603, when the work finally came out, Scaliger’s major difficulty was finding a publisher who was ready, willing and able to publish such a mighty tome:

From 1603 onwards, however, the worst and most frequent interruptions in Scaliger’s work were caused not by other scholars but by his own printers ... In the late autumn of 1603 Commelin [Jan, father of Isaac] finally found a printer for the book in Leiden, the ambitious Thomas Basson, who had never printed a book on anything like this scale of difficulty. Others had refused to undertake the large and demanding task, even though Scaliger had drawn up a magnificently legible final draft, much of which still survives as Leiden MS BPL 1909. ―Grafton 513

The completed work was published by Jan Commelin in Leiden in July 1606, a few weeks short of Scaliger’s 66th birthday. The English printer Basson and his workmen had proved hopelessly unequal to the task. The first edition was so full of typographical errors that Scaliger was ashamed of it. He immediately set about revising it, but he would not live to see the second edition through the presses. In his will he left instructions for his colleague Franciscus Gomarus to complete the task. As a token of his gratitude, Scaliger is thought to have allowed Gomarus a choice of any volumes from his personal library before the books were auctioned off. Gomarus chose Scaliger’s 1544 Basel edition of the works of Josephus (de Jonge 258–266).

Was Scaliger’s trust in Gomarus justified? Gomarus did make a serious, although unsuccessful, attempt in 1631–1632 to have the second edition of Scaliger’s Thesaurus temporum published by the press of Isaac Commelin in Leiden. ―van Miert 65

The second edition was not published until 1658, seventeen years after the death of Gomarus and almost half a century after the death of Scaliger. The task was finally accomplished by the Franco-Scottish Protestant theologian Alexander Morus (van Miert 234).

Scaliger himself probably has to bear some of the responsibility for the poor quality of the first edition. When he learned that the Bishop of Bazas Arnaud de Pontac was working on an edition of Eusebius’s Chronicle, he feared that Pontac’s Catholic edition might throw his Protestant one into the shade, which caused him to forge ahead with the printing of his own work. But his fears were unfounded. Pontac was no Scaliger, and when his edition came out in 1604, it failed to impress anyone. No doubt relieved not to have been scooped, Scaliger heaped much scorn on the hapless bishop in his private correspondence:

‛I would never have thought he was such a chamber-pot’, Scaliger wrote to Casaubon after seeing a specimen of Pontacus’ work ... Scaliger’s huge book stood alone, a masterpiece despite all its Schönheitsfehler [blemishes], something none of his rivals could possibly have produced. ―Grafton 514

References

- Henk Jan de Jonge, How Did Gomarus Acquire the Copy of Flavius Josephus in Greek from Scaliger’s Library? Nederlands archief voor kerkgeschiedenis, Volume 77, Number 2, Pages 258–266, Brill, Leiden (1997)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Elenchus trihaeresii Nicolai Serarii [A Refutation of “The Three Sects” of Nicolaus Serarius], Gilles van den Rade, Franeker (1605)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum, Jan Commelin (publisher), Thomas Basson (printer), Leiden (1606)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum, Second Edition, Johannes Janssonius, Amsterdam (1658)

- Dirk van Miert, The Emancipation of Biblical Philology in the Dutch Republic, 1590-1670, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2018)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger_: Gérard Edelinck (printmaker), Charles Eden Wagstaff (engraver), Charles Knight (publisher), Public Domain

- The Thesaurus Temporum: Joseph Juste Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum, Title Page, Jan Commelin, Leiden (1606), Public Domain

- The Frankfurt Fair in 1696: Johan Albrecht Jorman, Frankfurter Meßgedicht, (1696), Public Domain

- Johannes Drusius: Anonymous Portrait, Museum Martena, Franeker, Netherlands, Public Domain

- Franciscus Gomarus: Cornelis Koning (printmaker), Cornelis Danckerts (publisher), Public Domain

- Cathédrale Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Bazas: © Szeder László (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Alexander Morus: Wallerant Vaillant (artist), Bibliothèque nationale de Paris, Public Domain

Online Resources