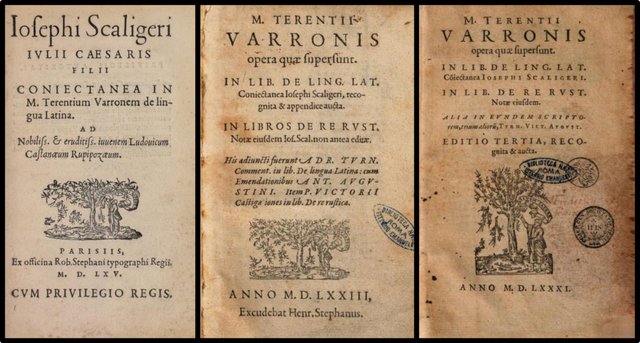

In 1565, about seven years after he had moved to Paris to study the classics, Joseph Juste Scaliger published his first work: the Coniectanea in M Terentium Varronem De Lingua Latina, or Conjectures on Marcus Terentius Varro’s Treatise on the Latin Language. Strictly speaking, this was not the first time Scaliger’s work as a fledgling philologist appeared in print. The previous year had seen the publication of Willem Canter’s Novae Lectiones [New Readings], which included some marginal notes by Scaliger on a recently discovered fragment of Athenaeus:

With younger Paris scholars Scaliger was on even closer terms. Indeed, he set up what amounted to a working partnership with Dorat’s pupil Willem Canter. When Muret came back from Italy, he brought with him a copy of a fragment of the Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus from a manuscript in the collection of the Farnese family. This section had been omitted from the printed editions of the full text. Muret passed it on to Canter for publication, and Canter turned to Scaliger for help with the many recondite and problematic words in it. The text appeared in Canter’s Novae lectiones of 1564, with Scaliger’s conjectures in the margin. Scaliger lent Canter his annotated Euripides—a course of action that he later regretted, for Canter copied out and published [Antwerp 1571] some of his conjectures without clearly identifying Scaliger as their author. All Scaliger could do was to decorate the offending passages in his copy of Canter’s work with indignant comments: ‛The man is ashamed to mention me’; ‛He took this from my Euripides, which I made available to him.’ But even this unfortunate incident did not break the friendship; as late as 1572, Scaliger proudly declared his affection for Canter in print. (Grafton 106)

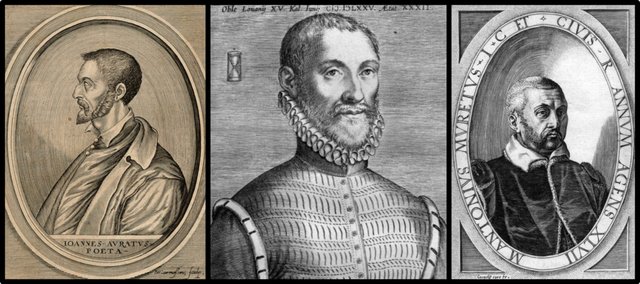

Like Scaliger, the Dutch scholar Willem Canter had been a pupil of Jean Dorat at the Collège Royal in Paris. Marc Antoine Muret had taught Latin at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux in 1547-48 before moving to Paris, where he became a prominent member of the city’s humanist movement.

Canter’s Novae Lectiones was a miscellany of more than eighty classical texts, with critical notes and emendations. Scaliger’s marginalia to the fragment of the Deipnosophistae can be found in Book 3, Chapter 11 (Pages 127-173), where they are marked with an S to distinguish them from Canter’s emendations. See, for example, Page 147, which contains five emendations by Scaliger.

The inclusion of Scaliger’s annotations in this publication is an indication of the repute in which the young man was already held by his fellow scholars:

These scattered references confirm Scaliger’s precocity as a master linguist and his remarkable ability at divining textual corruptions and emending them by conjecture. Even in the 1560s few humanists in their early twenties could argue convincingly for the creation of an unattested Latin form or the rewriting of a piece of Plato’s Greek; fewer still could command wide assent for their ideas from the most eminent professional philologists. (Grafton 106)

De Lingua Latina

Scaliger is believed to have started work on his annotations of Varro’s De Lingua Latina around 1560, when he was just twenty years of age (Grafton 107).

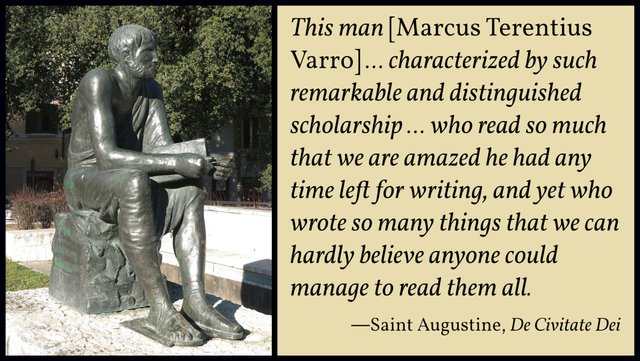

Marcus Terentius Varro was a polymath and one of the most prolific authors of ancient Rome. Widely regarded as the greatest scholar of the late Republic, only one of his many works has survived complete (De Re Rustica, or Three Books on Agriculture). Fragments are extant of dozens of other works. The most extensive of these are from his treatise Twenty-Five Books on the Latin Language. Of these, Books 5-10 are extant, though even these are marred by serious lacunae and corrupt passages. Scattered fragments of the remaining books have also survived, most of which can be found in the Noctes Atticae [Attic Nights] of Aulus Gellius.

Varro’s treatise was probably composed in the 40s BCE and published sometime before the death of Cicero, to whom it is dedicated, in 43:

The first book was an introduction ... The remainder seems to have been divided into four sections of six books each, each section being by its subject matter further divisible into two halves of three books each. (Kent ix)

Books 5-10, therefore, straddle Parts 1 and 2, comprising the second trilogy of Part 1 and the first trilogy of Part 2. The former deals with the origin of words and how they came to be applied to things, while the latter treats of the manner in which new words are derived from existing words—with a particular emphasis on the origins of grammatical inflection.

Scaliger used Antonio Agustin y Albanell’s edition of De Lingua Latina as his master text. This is the so-called Editio Vulgata. Antonius Augustinus was a Spanish historian of canon law and a Roman Catholic clergyman, who flourished in the middle of the 16th century. It is thought that he prepared his edition (Rome 1554) from Codex B, a 15th-century manuscript that can no longer be identified.

The text of De Lingua Latina has been regarded as greatly corrupted in this edition, since Augustinus based it on a poor manuscript, introduced a great number of his own emendations, and attempted a standardization of the orthography ... Despite his errors, he has made a number of valuable emendations ... The text of this edition was rather closely followed by all editors except Vertranius and Scioppius, and Scaliger in his emendations, until the edition of Leonhard Spengel in 1826. (Kent xxix-xxx)

Leonhard von Spengel’s edition (Berlin 1826) is the first modern—or “scientific”—edition. It is based on six of the best extant manuscripts—most notably the 11th-century Codex Laurentianus (F)—and a comparison of most of the preceding editions.

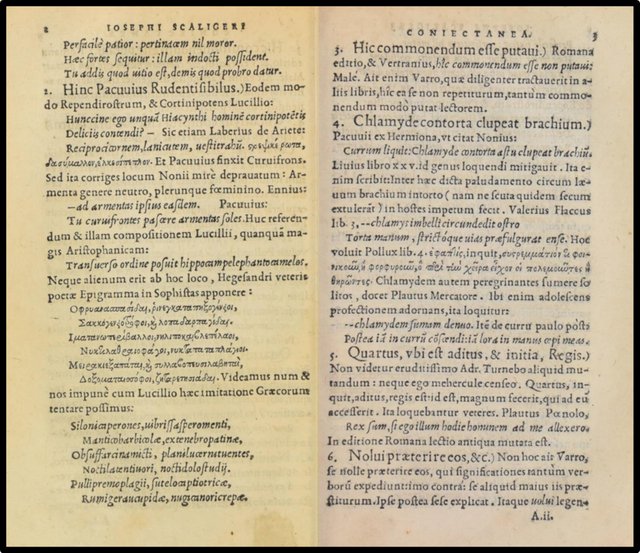

Coniectanea

In the context of Renaissance philology, the Latin term coniectanea is best translated by the English word conjectures—educated guesses made by philologists when correcting a corrupt passage in an old text. It is derived from the verb conicere, to conjecture, guess, infer, conclude (Lewis & Short 421). On the opening page of the book, Scaliger writes Coniectanea seu Annotationes: Conjectures or Annotations. Note that coniectanea is neuter plural, and not to be confused with the identically spelled feminine singular noun meaning memorandum or commonplace book.

In emending a classical text, Scaliger’s practice was quite different from that of a modern philologist, who would be expected to study as many of the surviving manuscript sources as possible, comparing and collating their texts, before making any emendations of his own. By restricting himself to a single printed edition, which was itself based on a single manuscript source, Scaliger was hamstringing himself.

As Roland Kent points out, Scaliger’s Coniectanea is not actually an “edition” of Varro’s treatise. It is, rather, a long list of annotations:

Coniectanea in M. Terentium Varronem de Lingua Latina, by Josephus Scaliger; not an edition, but deserving a place here, as it contains numerous textual criticisms as well as other commentary; written in 1564, and published at Paris in 1565. Both these Coniectanea and an Appendix ad Coniectanea (the original date of which I cannot determine [Geneva 1573]) are printed with many later editions of the De Lingua Latina. (Kent xxx)

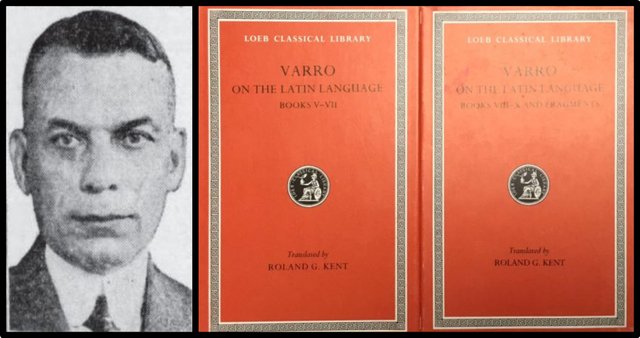

Kent’s translation of De Lingua Latina for the Loeb Classical Library cites Scaliger about fifty times in the apparatus criticus.

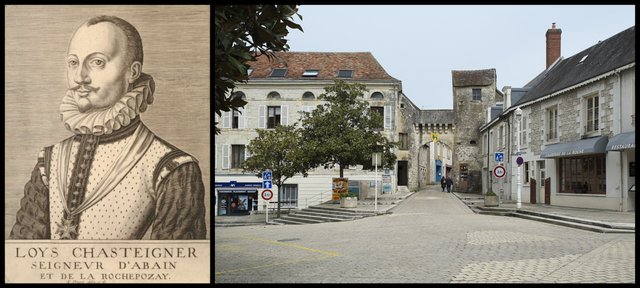

Scaliger’s Coniectanea is prefaced by a dedicatory letter to Scaliger’s friend and patron Louis Chasteigner de la Roche-Posay, Seigneur d’Abain. The first 82 pages proper of the Coniectanea comprise 251 annotations to Book 5 of Varro’s treatise, which is mistakenly referred to as Book 4. Scaliger continues this pattern for the following five books, numbering the annotations from 1 each time, and referring to these books as the 5th through the 9th. In Book 5, the annotations are numbered from 1-69, and then from 80-123. Presumably the jump from 69 to 80 on page 30 is a typographical error.

The misidentification of Varro’s Books 5-10 as Books 4-9, which is common to all the early editors, is commented on by Kent:

Two errors of earlier editors may be mentioned at this point. Since Varro in V:1 speaks of having sent three previous books to Septumius, our Book V was thought to be Book IV; and it was not until Spengel’s edition of 1826 that the proper numbering came into use. Further, Varro’s remark in 8:1 on the subject matter caused the early editors to think that they had De Lingua Latina Libri Tres (our V-VII), and De Analogia Libri Tres (our VIII-X); Augustinus in the Vulgate was the first to realize that the six books were parts of one and the same work, the De Lingua Latina. (Kent xxxii-xxxiii)

| Coniectanea | Pages | Varro (Augustinus) |

|---|---|---|

| Dedication | i-vi | - |

| 1-69, 80-251 | 1-82 | Book 5 (Quartum Librum) |

| 1-123 | 83-116 | Book 6 (Quintum Librum) |

| 1-258 | 117-201 | Book 7 (Librum Sextum) |

| 1-2 | 201 | Book 8 (Septimum Librum) |

| 1-4 | 201-202 | Book 9 (Octavum) |

| 1-2 | 202-204 | Book 10 (Nonum Librum) |

| Etymologies | 205-218 | - |

| Index of Authors | 219-221 | - |

It is curious that after averaging about 185 annotations for each of the first three books, Scaliger devotes only 8 to the last three books together. Did he lose interest after Book 7? Or are Books 8-10 simply free from the sorts of errors and difficulties that plague the earlier books?

To his conjectures, Scaliger appends an alphabetic list of Varro’s etymologies—from Aequor (Varro 7:23) to Urbs (Varro 5:143). The final three pages of the work comprise an index of authors cited in the text—from Aeschylus to Xenophon.

The book concludes with a Latin inscription:

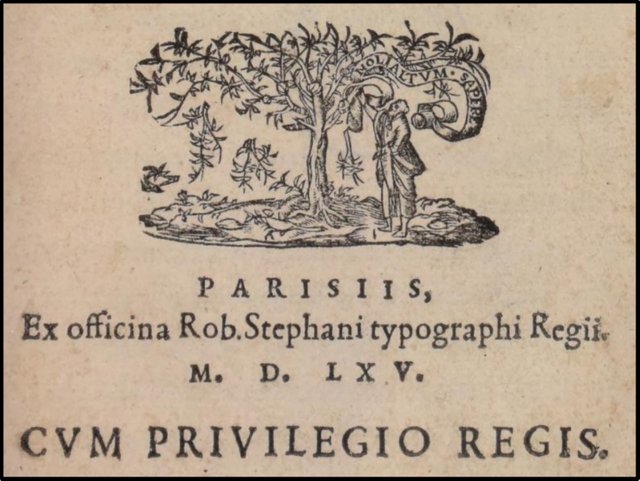

Printed by Robert Estienne, Royal Printer, in Paris, on the 10th Kalends of September, in the Year 1565.

This is Robert II Estienne, the son of Robert I Estienne and grandson of Henri Estienne the Elder, who founded the famous Parisian printing dynasty in 1502. The 10th Kalends of September is 23 August, or ten days before 1 September (inclusive).

Varro’s treatise was not the only text Scaliger was working at this time : it was simply the one he chose to polish off and present to the scholarly world as his calling card:

He clearly regarded the book as a sort of representative specimen of his best work in progress, for in his preface he stated that he had equally good sets of observations on other texts ready for publication, but had singled out those on Varro as a testimony of his gratitude to Louis Chasteigner, to whom he dedicated the whole.

Scaliger clearly set out to bring off a demonstration of virtuosity. He lost no chance to prove his mastery of Greek, even where he had to fetch the occasion for doing so from rather far ...

Even more decisively, the Coniectanea proved Scaliger’s mastery as a Latin textual critic. (Grafton 107-108)

Scaliger’s work was often quoted by other scholars without due credit being given to him—something which never failed to gall him. But he was often equally reluctant to acknowledge his own debt to others:

Scaliger’s conjectures reveal more than his cleverness. They show that he had learned from Turnèbe, in both method and substance, much more than he admitted in his preface or in his discursive remarks. He gave Turnèbe credit for having given him manuscript readings and discussed conjectures with him. The picture of detailed co-operation is confirmed by Turnèbe’s own approving citation of one of Scaliger’s emendations. But the many tacit correspondences between Scaliger’s work and Turnèbe’s expose debts that Scaliger wished to conceal. (Grafton 108-109)

Grafton draws some ineluctable conclusions from the Coniectanea:

Two inferences cannot be escaped. The first is that Turnèbe had far more to do with Scaliger’s training than has generally been realized. Scaliger’s marvellous gifts for conjectural re-creation did not develop with the spontaneity that his own account suggests. He learned from an older master how to identify and attack corruptions. The second is less pleasing. It is that Scaliger was a young man in a great hurry and, more important, that he was in a hurry to prove the validity of his father’s contention that the abilities of a della Scala were limitless and his originality complete. He understood the notion of intellectual property perfectly well when it suited him—he became quite angry, as we saw, when Canter pillaged his work without giving him due credit. But it did not suit him to admit that the critical approach that he applied to Varro—to say nothing of many specific results—was not his own. In short, Scaliger’s aim in this first work was not simply to produce a piece of solid, professional textual scholarship, but to prove that he was the aristocratic virtuoso that his father had wanted him to become, even at the expense of scholarly candour. (Grafton 109-110)

Grafton’s study of the Coniectanea has also convinced him that when Scaliger chose to begin his career as a classical scholar with Varro’s treatise on the Latin language, he had aesthetic reasons for doing so that had little to do with philology:

Scaliger’s interests were less historical than literary. He regarded the Latin poetry of the second century BC as the proper medium for translating the classics of Greek poetry. He may well also have reasoned that the second-century translations had naturalized Greek literature in Rome; they had been the common currency of the writers of the Roman Golden Age. But they had been imperfect and were in any case now lost. Accordingly, he set out to enrich the Latin culture of his own time by replacing and improving upon the lost originals. In mastering Varro he hoped to improve his own ability to write archaic Latin verse ... One central end of the Coniectanea, then, was not the purification of ancient texts but the reconstruction of an ancient poetic genre. (Grafton 113-114)

Second Edition

Scaliger was not one to rest on his laurels. Twice in the course of the next sixteen years he returned to his Coniectanea and revised it. The second edition came out in 1573, the third in 1581.

The second edition was published in Geneva by Henri II Estienne. This edition contains Varro’s De Lingua Latina and De Re Rustica. Scaliger’s Coniectanea and its revision, Appendix ad Conietanea, have been added as appendices. Also included in this volume are Scaliger’s annotations to De Re Rustica. In addition to numerous indices, this edition of Varro’s treatises also incudes commentaries and emendations by three other scholars: Scaliger’s former teacher Adrien Turnèbe : the original editor of Varro’s works Antonius Augustinus : and the Italian philologist Petrus Victorius.

| Contents | Page |

|---|---|

| Encomia on Varro | 1-2 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 5 | 1-45 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 6 | 45-69 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 7 | 70-91 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 8 | 92-111 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 9 | 112-140 |

| De Lingua Latina, Book 10 | 141-160 |

| 11 Indices | 76 Unnumbered Pages |

| De Re Rustica, Book 1 | 3-64 |

| De Re Rustica, Book 2 | 65-109 |

| De Re Rustica, Book 3 | 109-151 |

| Index | 18 Unnumbered Pages |

| Scaliger’s Coniectanea | 1-176 |

| Etymologies | 177-190 |

| Scaliger’s Appendix to the Coniectanea | 191-208 |

| Scaliger’s Notes to De Re Rustica | 209-276 |

| Indices | 23 Unnumbered Pages |

| Adrien Turnèbe’s Commentary on and Emendations to De Lingua Latina | 5-123 |

| Excerpts from Turnèbe’s Adversaria | 124-165 |

| Antonius Augustinus’s Emendations to De Lingua Latina | 166- |

| Index | 12 Unnumbered Pages |

| Petrus Victorius’s Commentary on De Re Rustica | 1-98 |

Books 5-10 of De Lingua Latina are once again misidentified as Books 4-9.

In the years between the first and second editions, Scaliger had studied with the French jurist Jacques Cujas at the University of Valence, in the Dauphiné. Much of what he learnt from Cujas is reflected in the second edition of Varro:

Scaliger’s other Latin undertakings, however, increasingly reveal the impact of Cujas. First, he published an edition of the works of Varro with Estienne. This was a reprint of Agustin’s De lingua latina and Vettori’s De re rustica as far as the texts were concerned. His Coniectanea on the De lingua latina he simply reprinted, adding an appendix in which he explained several passages in enormous detail, paying far more attention to details of Roman topography and history than he had in the original work. It is his notes on the De re rustica that are especially revealing. Vettori had based his edition on one particularly valuable manuscript, the readings of which he had recorded in detail in his Castigationum explicationes [Explanations of Emendations]. Scaliger reprinted Vettori’s notes in full; and in his own notes he repeatedly accepted Vettori’s views or based his own emendations on Vettori’s collations. ‛For this correction’, he wrote at one point, ‛as for innumerable others [drawn] from that excellent manuscript, we are indebted to that excellent scholar Vettori.’ In the earlier Coniectanea he had often discussed manuscripts and the habits of scribes, but always in general terms. He had never confronted, reading by reading, a major edition from Vettori’s school. In now doing so he clearly showed that he had learned from Cujas to use the detailed findings of the Italians as the basis for a bold and sophisticated conjectural criticism. (Grafton 127-128)

Third Edition

The third edition is little more than a reprinting of the second. It was published by Henri II Estienne in Geneva in 1581. Some of Scaliger’s contributions, however, have clearly been revised and enlarged. For example, his notes to De Re Rustica are about sixteen pages longer than in the second edition. The Coniectanea and its Appendix, however, appear to be unchanged from the second edition.

Scaliger is not known to have revisited his work on Varro during the remaining twenty-eight years of his life. By the time the third edition appeared, he was deep at work on his masterpiece De Emendatione Temporum.

Itaque hic finem faciam.

References

- Willem Canter, Novae Lectiones [New Readings], Johannes Oporinus, Basel (1564)

- Willem Canter, 19 Tragedies by Euripides, Christophe Plantin, Antwerp (1571)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Roland Grubb Kent (translator), Varro: On the Latin Language, Books 5-7, The Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1938)

- Roland Grubb Kent (translator), Varro: On the Latin Language, Books 8-10 and Fragments, The Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1938)

- Charlton T Lewis & Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1879)

- Joseph Scaliger, Coniectanea to Marcus Terentius Varro, De Lingua Latina, First Edition, Robert II Estienne, Paris (1565)

- Daniel J Taylor, Declinatio: A Study of the Linguistic Theory of Marcus Terentius Varro, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam (1974)

- Daniel J Taylor, De Lingua Latina X: A New Critical Text and English Translation with Prolegomena and Commentary, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam (1996)

- Marcus Terentius Varro, De Lingua Latina, De Re Rustica, Second Edition of Scaliger’s Coniectanea, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1573)

- Marcus Terentius Varro, De Lingua Latina, De Re Rustica, Third Edition of Scaliger’s Coniectanea, Henri II Estienne, Geneva (1581)

Image Credits

- Marcus Terentius Varro: Dino Morsani (sculptor), Rieti, © Alessandro Antonelli (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Jean Dorat: Nicolas de Larmessin (engraver), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Willem Canter: Philip Galle (engraver), Rijks Museum, Amsterdam, Public Domain

- Marc-Antoine Muret: Cornelis Cort (engraver), The New York Public Library Digital Collections, Public Domain

- Antonius Augustinus: Anonymous Engraving, Public Domain

- Roland Grubb Kent: © Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Fair Use

- Louis Chasteigner: Jean Picart (engraver), The British Museum, 1910,0610.39 London, Public Domain

- La Roche-Posay: © GFreihalter, Creative Commons License

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Hendrick Goltzius (engraver), Leiden University Libraries, Digital Collections, Public Domain

- Jacques Cujas: Anonymous, Court of Appeal of Toulouse, © Didier Descouens (photographer), Creative Commons License

Online Resources