After the publication of his edition of Marcus Manilius’s Astronomica, Joseph Juste Scaliger became embroiled in yet another public altercation. In his commentary on Manilius he had castigated several ancient writers for their ignorance of astronomy. Among these was Lucan, the author of the Pharsalia, an epic poem on the Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great. Scaliger’s scathing remarks had a lasting impact upon the critical reception of the Pharsalia:

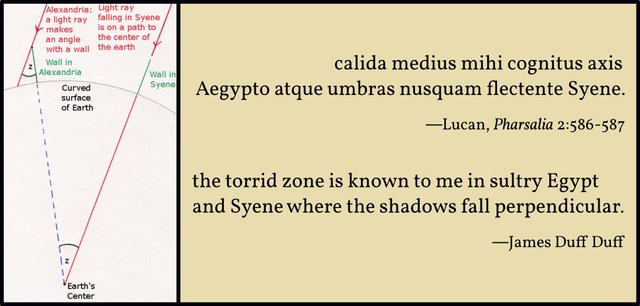

Scaliger condemned Lucan as a poet, first in his commentary on Manilius, and then in a direct letter to an adversary, at about the time that Kepler was cutting his teeth. Scaliger did not want anyone to read Lucan because he felt that Lucan’s astronomy was behind his own times, and because he constantly argued that all Roman poets were a thorn in the paw of astronomical progress. No criticism of Lucan, of which there were many throughout the ages, had such a damning effect on the poetry of Lucan. So great was Scaliger’s influence that even though Lucan was defended successfully against the particular attacks, the general bilious rhetoric (borrowed somewhat from Fronto) still echoes in the most recent English edition (Duff’s Loeb) of the Pharsalia, and almost any academic discussion of the poet. Thus Lucan’s condemnation is based, to a great degree, on a Renaissance desire for scholarship from poets. The irony in this case is that Lucan clearly attempted, to the limits of his stunningly catholic education, to present what we would call a realistic background of facts. Scaliger’s and later Housman’s attacks can be summed up like this: Lucan was not as good an astronomer or geographer as I am, therefore he was an inferior poet (both critics actually were accomplished poets). (Stevenson)

Scaliger’s comments drew the ire of one person in particular: François de Lisle, a prosecutor in the Parlement de Paris and a minor poet with a penchant for the writings of Lucan:

The first edition of the Manilius had appeared in 1579. Scaliger published a second edition in 1599. In the meantime his criticism of Lucan’s astronomy, which he had mingled with his review of Manilius’ errors on the same subject, was attacked quite strongly by François de Lisle (Insulanus), a prosecutor in the Parlement de Paris, in a poem published in 1582. De Lisle made the mistake of being at once: a passionate admirer of Lucan, a bad poet : a bad astronomer, despite being a mathematician : and very irascible. Any one of these would have been enough to give the advantage to an adversary, and perhaps even to induce one to be generous towards him. But, apart from the fact that Scaliger thought it very impertinent that anyone should come to the defense of a poet whom he had deigned to attack, he also remembered that having once spoken irreverently of the author of the Pharsalia in the presence de Lisle and some friends, de Lisle got so carried away that he would have come to blows if his good genius and, I imagine, his fear of the gendarmes (timor aliquis) had not called him back to reason. Not content, therefore, with demonstrating to de Lisle that he did not even know the language of the poet whose champion he had made himself, that barbarisms and solecisms came naturally to him, that he impudently offended against the rules of prosody, and that he did not understand more than the very rudiments of astronomy, he also called him ignorant, inept, imbecile, mad, and mangy. He was so blinded by anger that he did not seem to think that an enemy who covers himself with ridicule by the impotence of the blows he deals, sometimes becomes famous for the violence of those he receives.

But this outburst still did not relieve Scaliger’s pique. Anticipating that de Lisle was going to complain that he was being treated somewhat harshly (duriusculè), he did not delay in warning him that, in the event of a recurrence, he was preparing for him a dish of his own concoction—one with very different spices. This procedure of Scaliger’s might lead one to believe that, like du Jon, de Lisle had been his friend. We have seen, however, that he was not. Scaliger only knew him for having nearly fallen victim to his violent assault, and his lordship no doubt took pleasure in avenging the pittance of fear that an underling of the Basoche had had the audacity to cause him. What a pity that it did not occur to de Lisle—who, for a prosecutor, should have had more than one trick up his sleeve to avenge himself—to do what would one day work so well for Viète in similar circumstances. Having been insulted, like de Lisle, by Scaliger, Viète silenced Scaliger by calling him a Master of Grammar and threatening him with a defamation suit. On the contrary, de Lisle lowered his head and was himself silent.

Scaliger had nothing but contempt for Lucan, primarily on account of the poet’s ignorance of astronomy, but also on account of his arrogance. Furthermore, while he placed Virgil and the old Latin poets who preceded him in the sanctuary of poetry, he left Lucan, as he expressed it, in the antechamber. (Nisard 204-206)

To be fair to de Lisle, Scaliger’s squabble with the mathematician François Viète took place in 1590, about ten years after the row with de Lisle, so the latter can hardly be faulted for not adopting the tactics that would one day work wonders for the former.

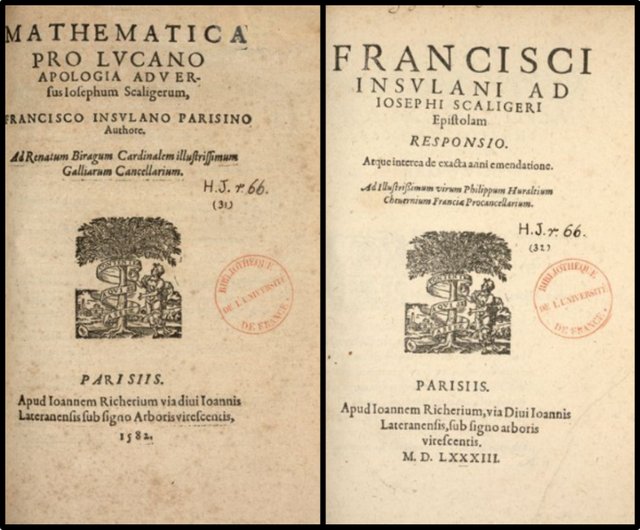

De Lisle’s 536-line poem, Mathematica pro Lucano Apologia adversus Iosephum Scaligerum [A Mathematical Apology for Lucan against Joseph Scaliger] was published in Paris in 1582, with the byline: autore Insulano Parisino procuratore [written by de Lisle, Parisian Prosecutor].

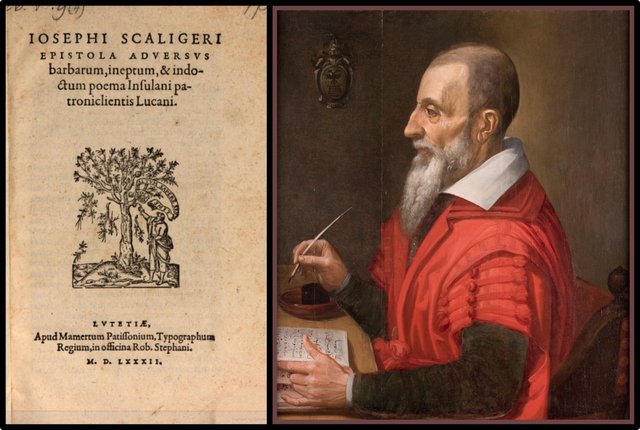

Scaliger’s response was expressed in an eighteen-page open letter in prose with the title Epistola adversus barbarum, ineptum et indoctum poema Insulani patroniclientis Lucani [Epistle against the Barbarous, Inept and Unlearned Poem of Insulanus, Patronizer of Lucan, which was published in Paris in 1582. In this epistle Scaliger lists all the astronomical errors in Lucan’s poem, demonstrating the scientific [in]accuracy of the poet, as well as the incompetence of de Lisle (Stevenson).

The French philologist Charles Nisard is incorrect when he says that de Lisle simply lowered his head and remained silent in the face of Scaliger’s onslaught. On the contrary, in 1583 he published a response to Scaliger’s open letter: Francisci Insulani ad Iosephi Scaligeri epistolam responsio. Like his first broadside, this 525-line invective was written in verse. Despite his former threats, however, Scaliger did not deign to reply—at least not publicly—and the controversy died down. Anthony Grafton notes the following source, which perhaps explains why Scaliger did not follow through:

... a further reply to de Lisle, not in Scaliger’s hand, is preserved in MS Dupuy 810, fols. 88 r -90 v, under the title ‛C. Thaletis Valerii Epistola ad Jos. Scaligerum admonens ut insano versificatori Francisco Insulano ne respondeat’ [Epistle of Caius Thaletis Valerius to Joseph Scaliger, Admonishing Him Not to Answer the Mad Versifier François de Lisle]; it is dated July 1583. This seems to be another of Scaliger’s pseudonymous pamphlets, or at least one written in imitation of his style. (Grafton 1983:335)

Caius Valerius are the forenames of the Roman poet Catullus, whose elegies Scaliger had edited in 1577. Thales or Thaletas may refer to the Cretan lyric poet of that name—an “islander” like Insulanus.

The altercation with de Lisle was a minor distraction from Scaliger’s other literary activities at this time. In 1581—after the publication of his Manilius but before the appearance of de Lisle’s first poem—the third edition of Scaliger’s Varro came out in Geneva. Printed by Henry II Estienne, it was advertised on its title page as Recognita et aucta: Revised and enlarged. It was little more than a reprinting of the second edition of 1573. The majority of these years, however, Scaliger devoted to a much more important task—one that would result in his most famous work.

References

- Pierre Desmaizeaux (editor), Scaligerana, Thuana, Perroniana, Pithoeana, et Columesiana, Volume 2, Prima Scaligerana, Secunda Scaligerana, Covens & Mortier, Amsterdam (1740)

- James Duff Duff (translator), Lucan: The Civil War, Books 1-10 (Pharsalia), Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1962)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Anthony Grafton, From De die natali to De emendatione temporum: The Origins and Setting of Scaliger’s Chronology, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Volume 48, Pages 100–143, The Warburg Institute, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1985)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Philippe Tamizey de Larroque (editor), Lettres Françaises Inédites de Joseph Scaliger, Alphonse Picard, Paris (1884)

- François de Lisle, Mathematica pro Lucano Apologia adversus Iosephum Scaligerum, Jean Richer, Paris (1582)

- François de Lisle, Francisci Insulani ad Iosephi Scaligeri Epistolam Responsio, Jean Richer, Paris (1583)

- Charles Nisard, Le triumvirat littéraire au 16e siècle: Juste Lipse, Joseph Scaliger, et Isaac Casaubon, Amyot, Paris (1852)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Marcus Manili Astronomicon, First Edition, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1579)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, M Terentii Varronis Opera, Third Edition, Robert III Estienne Paris (1581)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Epistle against the Barbarous, Inept and Unlearned Poem of Insulanus [François de Lisle], Patronizer of Lucan, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1582)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, De Emendatione Temporum [On the Correction of Dates], First Edition, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1583)

- Walter Stevenson, Kepler on Lucan, Work in Progress, University of Richmond, Online (18 July 1991)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Jan Cornelis Woudanus (artist), Icones Leidensis, Number 31, Senate Chamber, Academy Building, Leiden University, Public Domain

- Lucan on Syene: © FamousScientists (designer), Fair Use

- Model of the Palais de la Cité, Paris, in the Late 16th Century: Musée Carnavalet, Paris, © Adrian Scottow (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Marcus Terentius Varro: Dino Morsani (sculptor), Rieti, © Alessandro Antonelli (photographer), Creative Commons License

Online Resources