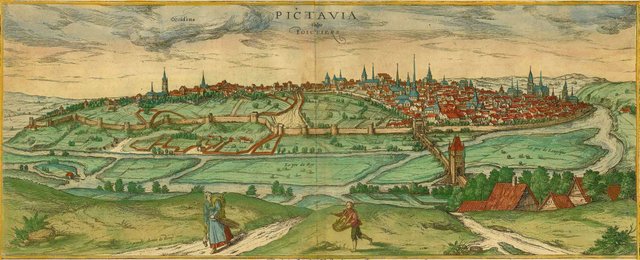

The French physician and scholar François Vertunien is hardly known today. But when he is remembered, it is for his friendship with Joseph Juste Scaliger. Vertunien was born in Poitiers to a Calvinist father variously referred to as Vertunien, Saint-Vertunien, and de Lazau. The year of his birth is unknown but he is thought to have been of an age with Scaliger, who was born in 1540. Vertunien père had played a prominent rôle in helping to establish Calvinism in the French province of Poitou, even to the point of crossing theological swords with Calvin himself. The son took degrees in medicine at the University of Montpellier in 1567 and 1568, after which he began a medical practice in his native Poitiers. He excelled in his chosen craft and became celebrated as a physician. Among his patients were several aristocratic families of the province, including the Chasteigners de la Roche Posay, under whose protection Joseph Scaliger lived.

It was no doubt through his patrons that Scaliger first became acquainted with Vertunien. As we have seen, Scaliger returned to France in the summer of 1574, after spending about two years teaching and studying in Geneva:

The earliest dated evidence of the friendship between Scaliger and Vertunien is five letters written in Latin by Scaliger to Vertunien in December, 1574, and in January, February, and March, 1575, dealing with the names of plants corrupted by Dioscorides, Pliny, and other ancient naturalists, a subject of interest to Scaliger as a philologist, to Vertunien as a physician. From 1574 to 1593, on account of their connection with the Chasteigner family, they were more or less constantly in each other’s company, and information concerning their relations is comparatively abundant. (Hawkins 126 : Heinsius 103-127)

There is some evidence, however, that the two men were known to each other prior to 1574:

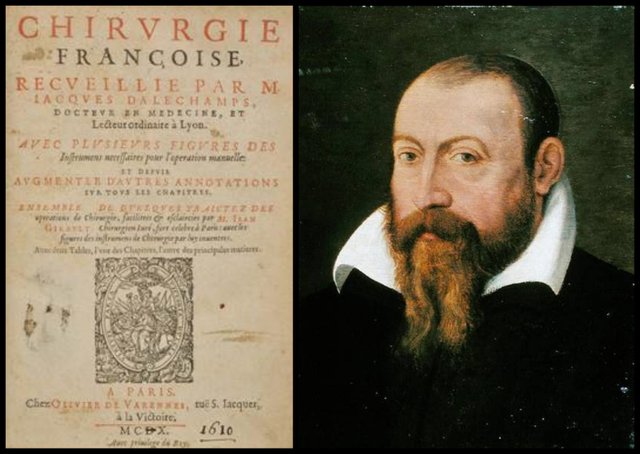

That Scaliger and Vertunien were acquainted before 1574 is shown by an undated letter written by Scaliger to Jacques Daléchamps between 1561 and 1571 (probably about 1565) ... (Hawkins 126 fn 45 : Bernays 309)

In that letter Scaliger informs Daléchamps, a botanist and physician from Lyon, that he would already have sent him the edition of Seneca that Daléchamps wanted if he, Scaliger, had been currently living where his library was located. Apparently, Scaliger’s library was in the Château d’Abain at Thurageau, about 20 km north of Poitiers. Scaliger assures Daléchamps that he will have the Seneca as soon as possible from the hands of a merchant from Poitiers or from those of Monsieur de La Vau, a medical doctor. The letter was written from another Chasteigner property, the Château de Chantemille, in La Marche, 140 km southeast of Poitiers.

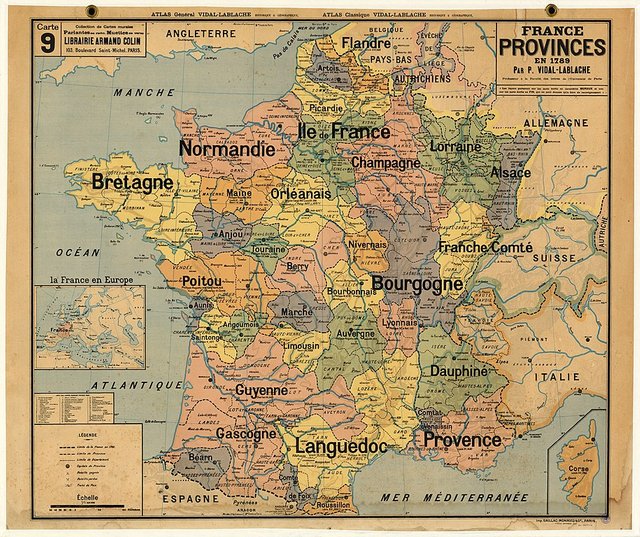

In 1576 the religious wars had been in progress in France for nearly fifteen years. Four of the eight wars had been fought, and the fifth was coming to a close with the convocation of the States-General at Blois. The domains of the Chasteigner family were situated in Poitou, Limousin, Touraine, and Marche, provinces in which the Huguenots were particularly strong, and which consequently were the scenes of the most bitter conflicts and the most unbridled lawlessness. Scaliger, through his connection with the Chasteigners, suffered many hardships at this time. (Hawkins 129)

Despite the exigencies of camp life, which saw Scaliger constantly on the move from château to château, sometimes even being required to do guard duty, he still managed somehow to continue his precious studies:

... with no access to libraries, and frequently separated even from his own books, his life during this period seems in one aspect most unsuited to study. He had, however, what so few contemporary scholars possessed—leisure, and freedom from pecuniary cares. In general he could devote his whole time to study; and it was during this period of his life that he composed and published the books which showed how far he was in advance of all his contemporaries as a scholar and a critic, and that with him a new school of historical criticism had arisen. His editions of the ‛Catalecta’ (1574), of Festus (1576), of Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius (1577), are the work of a man who writes not only books of instruction for learners, but who is determined himself to discover and communicate to others the real meaning and force of his author. (Christie 216)

As physician to the Chasteigners, Vertunien too shared in these trials. Hawkins quotes from an unpublished letter Vertunien wrote many years later, in which he describes the life he and Scaliger led during a period of nine or ten months in 1577 when they were confined to the Château de Touffou, another Chasteigner stronghold in Poitou, about 18 km east of Poitiers. Scaliger took the opportunity to instruct Vertunien in the finer points of Greek composition, employing the same methods that his father, Julius Caesar Scaliger, had used to teach him Latin composition:

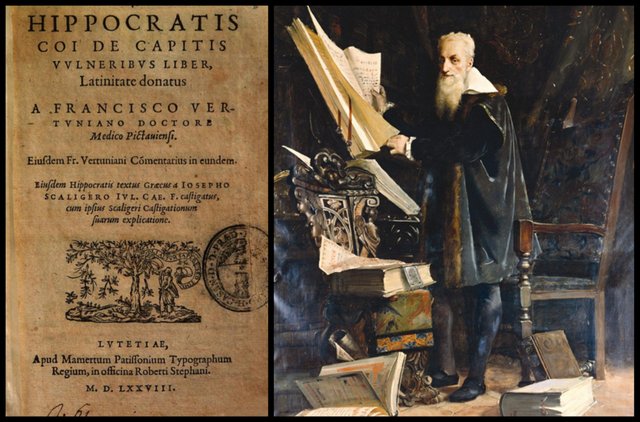

We both withdrew to Touffou, the house of the late Monsieur de la Rochepozay, four leagues from this city [Poitiers], for the First War of the League, 1577, during the first States-General of Blois, where, lying down in his room, he instructed me in the Greek language, telling me that there was nothing better than making versions of one language in the other: and therefore made me translate Hippocrates’ treatise On Wounds in the Head, the compendium edition of whose works, published in Paris by Mamert Patisson, had caused such a stir. (Hawkins 130)

A letter which Scaliger wrote at Touffou on 30 June 1577 has also survived:

I am not entirely alone in this château. I speak of a companion who can content a man of my humour, for, among others, Monsieur de La Vau, a doctor, is here with me, who has been toiling away at Hippocrates’ treatise On Wounds in the Head. For this book having been cleansed by me of a thousand faults and glosses that had been stuffed into the text of this great man, Vertunien translated it into good Latin, illustrating it with a very fine commentary and correcting many of the errors of modern scholars. In short, it has been time well spent. I must find out whether Mamert Patisson will be willing to print it with my criticisms. You will discover that since the revival of learning, no book has been made so new again as this work of Hippocrates ... Monsieur de La Vau ... is eager to cultivate your friendship. For he knows that you, like him, have an insatiable appetite for learning ... (Hawkins 131 ... 132, my translation)

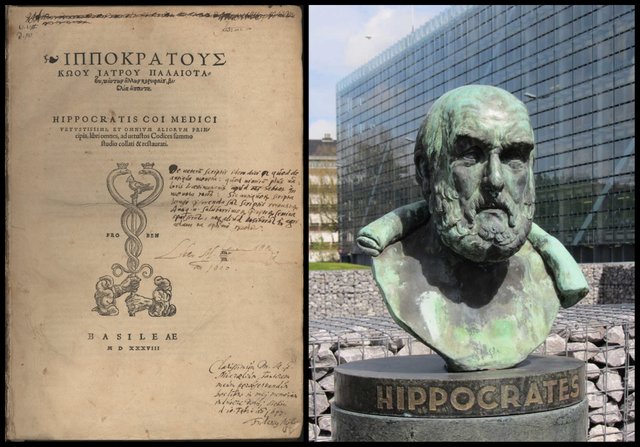

The edition of Hippocrates’ treatise that Scaliger used had been published by Hieronymus Froben & Nikolaus Episcopius in Basel in 1538. It was the 48th treatise in this Greek edition of the Corpus Hippocraticum, a collection of sixty treatises attributed to the ancient physician. This particular treatise, which can be found on pages 445-456, had been known to include spurious additions since the time of Galen. These additions—pages 451 ff—are explicitly identified as such on Galen’s authority (Grafton 182, 318 fn 12).

... reading Hippocrates reawakened in [Scaliger] a long-standing interest in natural science, one that had expressed itself in several letters to Vertunien and to the Plinian scholar Jacques Daléchamps. He decided that he had found a new and crucial key to the interpretation of the Hippocratic text. It was riddled with. interpolated words and phrases, which previous editors had failed to notice. Scaliger worked through it twice, the second time more carefully. He made a number of emendations and excised both words and phrases, dictating to Vertunien a few notes on specially problematic or interesting points. Vertunien prepared a Latin translation of and commentary on the corrected text, which were well advanced by 30 June and complete by the end of the year. Mamert Patisson printed them, along with Scaliger’s comments and the Greek text, during 1578. (Grafton 180-181)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger & François Vertunien, Hippocrates: On Wounds in the Head, Critical Edition by Nicolas Vincent, Surgeon of Poitiers [ie Joseph Scaliger], with a Latin Translation and Commentary by François Vertunien, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1578)

Julius Caesar Scaliger had been a physician and a keen student of botany, so it is not surprising that his son too took an interest in these fields. But both he and Vertunien were at pains to exalt the art of criticism above that of medicine. In his preface, Vertunien put it baldly and with little tact:

I shall try to restore Hippocrates’ true meaning, using Scaliger’s emendations. [I shall] show everyone how far all the doctors and surgeons who have dealt with this work—men admirable in other respects—were from understanding Hippocrates, because of their ignorance of the art of Criticism. (Grafton 181-182 : Scaliger 44)

Scaliger Courts Controversy

Grafton considers this volume to be as much polemical as it was critical:

Vertunien’s and Scaliger’s work amounted to more than a new edition of Hippocrates on wounds to the head; it was itself a blow to the head of the medical profession. It was a manifesto that proclaimed that the doctors did not know how to interpret the authoritative classical texts on which their claims to professional authority rested. (Grafton 182)

Although Scaliger was far from being the first modern scholar to recognize that several sections of the treatise were late and spurious additions, Vertunien nevertheless commended “our Aristarchus” for having “smelled out” these encrustations independently of any possible precursors:

What apparently did not occur to either Scaliger or Vertunien was that their claims sounded somewhat arrogant, given that they had merely elaborated upon a discovery made by the very doctors they despised. Presumably both knew that their work was bound to provoke controversy of a sort. But they seem to have been unprepared for the sharpness of the doctors’ response. (Grafton 183)

On 11 November 1575, in one of his letters to Vertunien, Scaliger had mentioned various physical ailments from which he was then suffering:

After mentioning the dangers that beset wayfarers, Scaliger enumerates his bodily ills: he has had a fever, a cough, a cold, a catarrh; he came near breaking his sacrum, and his entire body is covered with itch. (Hawkins 126)

In Scaliger’s own words:

I felt so much pain, that I might have celebrated [concinuerim] almost the whole neighborhood with the cries and helplessness of pain. Nor was there any rest, until Duretus, whose services I had employed, ordered me to be bled again, on account of that sudden attack of pain, since six days before my vein had also been opened. (Hawkins 127)

Of this Duretus, Hawkins comments:

Louis Duret (1527-1586), physician of Charles IX and of Henry III, was appointed professor in the Collège Royal in 1568. He excelled in explaining the works of Hippocrates. (Hawkins 128 fn 48)

Louis Duret was celebrated in his day as both a doctor of medicine and a humanist scholar. He is said to have been possessed of such a prodigious memory that he knew the Corpus Hippocraticum by heart. As a young man he tutored the future French magistrate Achille de Harlay, to whom Scaliger would dedicate the first edition of his masterpiece De Emendatione Temporum. Among Duret’s writings are two books devoted to the works of Hippocrates. Although he worked on these over many years, they were not published until 1588 and 1631. Nevertheless, Duret claimed that many of Scaliger’s emendations of Hippocrates had been taken from him:

[Duret] was enraged by Scaliger’s sneers at his colleagues—especially, perhaps, by the ingratitude they showed. He tried to have the edition suppressed; he claimed that Scaliger had plagiarized from him; and he induced a younger doctor, Jean Martin, to denounce the book in public lectures. (Grafton 183)

Scaliger, of course, could not let such an insult pass unrequited. As usual, he insisted on having the last laugh:

Scaliger had his revenge. In a wicked pseudonymous pamphlet he tore Duret apart for everything from slipping from Latin into French while lecturing to relying supinely on grammars and dictionaries. Martin fared even worse ... Having crushed Martin, Scaliger sprayed a final burst of venom over Duret’s translation of the Aphorisms of Hippocrates, the Latin style of which, he remarked ‛has a certain divine quality to it’. (Grafton 183)

The response was published in Cologne in 1578 under Scaliger’s pseudonym Nicolas Vincent, Surgeon of Poitiers. It took the form of a lengthy open letter of almost one hundred pages and was addressed to a certain Stéphane Naudin of Bresse. By this name Scaliger obviously meant Louis Duret, who came from the French Province of Bresse in Burgundy:

- Vincentii Epistola, Nicolas Vincent, Surgeon of Poitiers [Joseph Scaliger], Epistle to Stéphane Naudin of Bresse [Louis Duret] Concerning the Lectures of Jean Martin on Hippocrates’ Book On Wounds to the Head, Sebastian Faucher, Cologne (1578)

Nicolas, a name of Greek origin, is derived from the words for victory and people. Vincent is of Latin origin and means conquering. A Classical scholar like Scaliger could hardly have devised a more appropriate nom de guerre.

Grafton concludes his brief discussion of this curiosity with the following laconic remark:

The polemic was undeniably amusing. For our purposes it is also important, because of the attitude that it reveals: namely, that Scaliger was more competent than professional scientists to explicate and correct classical scientific texts. (Grafton 183-184)

Prima Scaligerana

Scaliger and Vertunien remained close for the following decade-and-a-half. Vertunien spent most of this time in Poitiers, where he continued to practise medicine and where he and Scaliger often met. It was only after Scaliger moved to Leiden in the Netherlands in 1593 that their close relationship was finally severed.

There are a few scattered pieces of documentary evidence concerning the relations of Scaliger and Vertunien during the fifteen years that followed the publication of Hippocratis Coi De Capitis Vulneribus Liber. Nearly all this period was spent by Scaliger in the various châteaux of the Chasteigner family, Chantemille, Touffou, Preuilly, and especially Abain, where he devoted himself to his De Emendatione Temporum and other chronological works. That Vertunien saw Scaliger and corresponded with him at this time is shown by Scaliger’s letters to his friends, in which he mentions the reception of books and letters through the medium of Vertunien. (Hawkins 134)

In 1593 Scaliger moved from France to Leiden, in the Netherlands, where he would spend the remaining sixteen years of his life.

The Prima Scaligerana, a collection of Joseph Scaliger’s table talk, is the enduring legacy of the friendship of Scaliger and Vertunien. Throughout the twenty years of their acquaintanceship Vertunien had been jotting down anything he considered interesting that fell from the lips of the “Phoenix of scholars.” When Vertunien died in 1607—two years before Scaliger—the manuscript of these bons mots passed through various hands:

Through a peculiar chain of circumstances the Prima Scaligerana was published a century after Vertunien began jotting down the observations that fell from Scaliger’s lips. Upon Vertunien’s death in 1607 the manuscript passed into hands now unknown, where it remained until purchased by François de Sigogne, a lawyer of Poitiers, who sent it to Saumur to be printed after it had been revised by Tanneguy Le Fèvre. (Hawkins 136-137)

The volume was finally published in Saumur, in the Province of Anjou, in 1669 under a title chosen by Le Fèvre:

Prima Scaligerana, nusquam antehac edita, cum Praefatione T. Fabri; Quibus adjuncta et altera Scaligerana quam antea emendatiora, cum Notis cujusdam V. D. anonymi

First Scaligerana, never published before, with a Preface by T Le Fèvre; To which are added other Scaligerana in an edition more correct than previous editions, with the Notes of a certain anonymous V. D.

- François Vertunien, Scaligerana Vertuniani, The Table-Talk of Joseph Scaliger, Recorded by François de La Vau de Saint-Vertunien, Edited by Tanaquil Faber [Tanneguy Le Fèvre], Saumur (1669)

The title page claims that it was published by Petrus Smithaeus in Groningen, but this is not true. The other Scaligerana were compiled in Leiden between 1604 and 1606 by Jean de Vassan and his brother Nicolas. The anonymous V. D. who provided the notes was the Huguenot librarian Paul Colomiès.

The public row between Scaliger and Duret had another and more lasting impact on Scaliger’s career:

For it was while he was engaged in the polemic over Hippocrates that Scaliger came across the copy of Manilius’ Astronomica that he had worked on while in Geneva. He decided that this text too had been either neglected or mistreated by modern practitioners of its subject. Hence, it too called for the ministrations that only a critic with Scaliger’s gifts could provide. (Grafton 183-184)

And so it was that Scaliger finally returned to a study of Manilius.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Richard Copley Christie, Selected Essays and Papers, Longmans, Green, and Co, London (1902)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Richmond Laurin Hawkins, The Friendship of Joseph Scaliger and François Vertunien, The Romantic Review, Volume 8, Number 2, Pages 117-144, 307-327, Columbia University Press, New York (1917)

- Daniel Heinsius (editor), The Correspondence of Joseph Juste Scaliger, Bonaventura & Abraham Elzevir, Leiden (1627)

- Hippocrates (attributed), The Collected Works of Hippocrates of Cos, Hieronymus Froben & Nikolaus Episcopius, Basel (1538)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger & François Vertunien, Hippocrates: On Wounds to the Head, Critical Edition by Nicolaus Vincentius Pictaviensis Chirurgus [Nicolas Vincent, Surgeon of Poitiers = Joseph Scaliger], with a Latin Translation and Commentary by François Vertunien, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1578)

- Nicolas Vincent, Epistle to Stéphane Naudin of Bresse [Louis Duret] Concerning the Lectures of Jean Martin on Hippocrates’ Book On Wounds to the Head, Sebastian Faucher, Cologne (1578)

- Edward Theodore Withington (translator), Hippocrates, Volume 3, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1959)

Image Credits

- Hippocrates Refusing the Gifts of Artaxerxes: Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (artist), Museum of the History of Medicine, Paris, Public Domain

- Jacques Daléchamps: Pierre Eskrich (artist), Musée des Hospices civils de Lyon, Lyon, Public Domain

- Château de Chantemille: © Aubussonais (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Château de Touffou: Donniedarko37 (photographer), Musée des Hospices civils de Lyon, Lyon, Public Domain

- Bust of Hippocrates at Leiden University: Oswald Wenckebach (sculptor), Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, © Gouwenaar (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Scaliger and the Frontispiece of Hippocrates’ On Wounds in the Head: Antoine Calbet (artist), La Salle des Illustres de l’Hôtel de Ville d’Agen, Agen, Pôle Mémoire et Archives d’Agen (photo), Public Domain

- Poitiers in 1561: Georg Hoefnagel (artist), Georg Braun & Franz Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Volume 5, Page 18 (1597), Public Domain

- Charles IX of France: Anonymous Artist, After François Clouet, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, Public Domain

- Henri III of France: Étienne Dumonstier (attributed), National Museum in Poznań, Poznań, Poland, Public Domain

- French Provinces in 1789: Paul Vidal de La Blache (cartographer), Librairie Armand Colin, Paris (1942), Public Domain

- Château des Lions de Preuilly-sur-Claise: Musée de la Poterne, Former Entrance of the Château des Lions, Preuilly-sur-Claise, © DoucF (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Tanneguy Le Fèvre: Frans van Bleyswyck (engraver), Public Domain