In the summer of 1573, when Joseph Juste Scaliger was living and teaching in Geneva, he hatched several philological projects that would never see the light of day. In August he wrote to his colleague Pierre Pithou, seeking the loan of manuscripts of Roman grammatical works:

Your brother mentioned to me that he had left with you a Censorinus, and a Probus on Juvenal. He assured me that if I asked you for them, you would not refuse me, indeed, that you would willingly make them available to me. Well, since I have decided to publish Gellius, Macrobius, and Censorinus together, and have much to say on those authors, it would be most helpful to me if you were willing to let me use both the aforementioned manuscripts and your learned conjectures and notes on the aforementioned authors ... (Tamizey de Larroque 20-21)

The following month, he wrote again to Pithou, renewing his request. In this letter he laid out his plans for three projects (Tamizey de Larroque 25-26):

A corrected edition of the works of Gellius, Macrobius and Censorinus.

A corrected edition of Marcus Manilius’s Astronomica.

An edition of the satirists Juvenal and Persius, with the scholia to Persius attributed (incorrectly) to Lucius Annaeus Cornutus.

Of these projects, only the second would be completed. In fact, Scaliger claims in his letter of 10 September 1573 that he has already brought his work on Manilius to fruition. But Scaliger put this work aside for the moment, only returning to it in 1575. It would not pass through the printing press until 1579. Meanwhile, he took up a new project, which undoubtedly benefited from the research he had already carried out for his planned edition of Gellius, Macrobius and Censorinus: an edition of the work of Sextus Pompeius Festus.

Sextus Pompeius Festus

Sextus Pompeius Festus was a Roman grammarian who flourished, it is thought, in the 2nd or 3rd century of the Common Era. We know little or nothing of his life. He quotes Martial, who died around 102-104 CE—but this is now thought to be a later addition (Grafton 142)—and is referred to by Macrobius, who flourished around 400 CE. He is often associated with Narbonne in Gaul, but the evidence for this is scanty:

Festus the man is obscure; even the elements of his name are uncertain. The hypothesis that he came from Gaul largely derives from an entry in a mid-twelfth century monastic catalogue at Cluny which records a liber Festi Pompeii ad Arcorium Rufum, identified as a descendant of the grammarian C. Artorius Proculus, whom Festus cites. Inscriptions at Narbonne may also suggest a connection between the two families (CIL 12.4412, 12.5066). However, Festus’ Gallic origin remains unproven. (Fay Glinister, The Literary Library)

Festus is best known for his epitome of the De Significatu Verborum (On the Meaning of Words). This voluminous Latin dictionary was compiled by Marcus Verrius Flaccus, an antiquarian and grammarian who flourished during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius and who served as tutor to two of Augustus’s grandsons. Only fragments of Flaccus’s work survive, but its encyclopaedic scope is indicated by the fact that Festus’s abridgment runs to twenty volumes. Festus’s work is usually referred to as Sexti Pompeii Festi de Verborum Significatione.

The first half of Festus’s work is no longer extant, but an epitome made for Charlemagne in the 8th century by Paul the Deacon survives. Several glossaries compiled in the early Middle Ages also contain material from Festus.

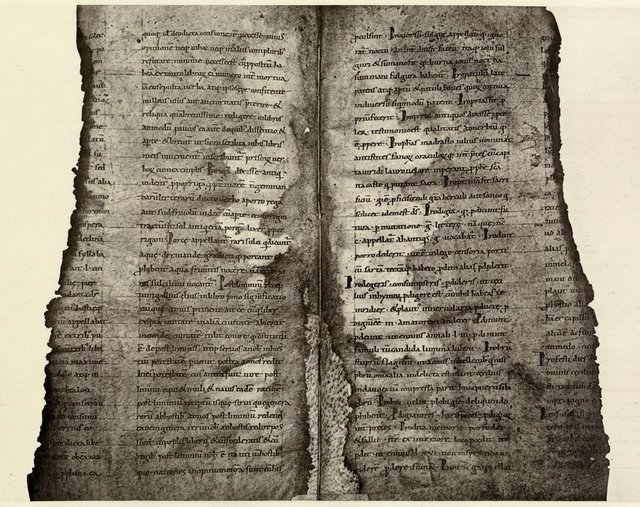

In his abridgment Festus emended Flaccus’s text, inserting some additions of his own, removing obsolete Latin words, and correcting errors where he found them. He planned to publish a lexicon of the obsolete words as a separate work, but no such work survives—if it was ever written. What remains of his epitome can be found in a single medieval manuscript, the Codex Festi Farnesianus, at Naples. The interesting history of the provenance and fate of this manuscript is given in William Smith’s A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology:

Of the abstract by Festus one imperfect MS. only has come down to us. It was brought, we are told, from Illyria, and fell into the hands of Pomponius Laetus, a celebrated regarded scholar of the fifteenth century, who for some reason now unknown kept possession of a few leaves when he transferred the remainder to a certain Manilius Rallus, in whose hands they were seen in 1485 by Politian, who copied the whole together with the pages retained by Pomponius Laetus. This MS. of Rallus found its way eventually into the Farnese library at Parma, whence it was conveyed, in 1736, to Naples, where it still exists. The portion which remained in the custody of Laetus was repeatedly transcribed, but it is known that the archetype was lost before 1581, when Ursinus published his edition.

The original codex written upon parchment, probably in the eleventh or twelfth century, appears to have consisted, when entire, of 128 leaves, or 256 pages, each page containing two columns; but at the period when it was first examined by the learned, fifty-eight leaves at the beginning were wanting, comprehending all the letters before M; three gaps, extending in all to ten leaves, occurred in different places, and the last leaf had been torn off, so that only fifty-nine leaves were left, of which eighteen were separated from the rest by Laetus and have disappeared, while forty-one are still found in the Farnese MS. In addition to the deficiencies described above, and to the ravages made by dirt, damp, and vermin, the volume had suffered severely from fire, so that while in each page the inside column was in tolerable preservation, only a few words of the outside column were legible, and in some instances the whole were destroyed. These blanks have been ingeniously filled up by Scaliger and Ursinus, partly from conjecture and partly from the corresponding paragraphs of Paulus, whose performance appears in a complete form in many MSS.

This epitomizer, however, notwithstanding his boast that he had passed over what was superfluous and illustrated what was obscure, was evidently ill qualified for his task; for whenever we have an opportunity of comparing him with Festus we perceive that he omitted much that was important, that he slavishly copied clerical blunders, and that when any expression appeared perplexing to his imperfect scholarship he quietly dropped it altogether. He added a little, but very little, of his own, as, for example, the allusion to his namesake, the apostle (s. v. barbari), and a few observations under secus, sacrima, signare, posimerium, porcas, &c. (Smith 148)

The subsequent history of the text is summarized by Anthony Grafton in Volume 1 of his Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, but that history is quite complicated and of little relevance to our subject. By the time Scaliger entered the fray, this is how things stood:

It was only natural that scholars should seek to provide a more reliable edition of so rich a text, and a full commentary on it. In the late 1550s, both Carlo Sigonio and Antonio Agustín undertook editions. After a few months of competition, Sigonio agreed to give up his project in favour of seeing Agustín’s through the press. Agustín’s text, published in 1559, became the dominant one for the next two centuries and more ...

He traced the history of the text, as we have seen, and used it as the basis of his editorial practice. Since Verrius Flaccus was the ultimate source of most of Festus’ material, Agustín began his work with a comprehensive collection of testimonia and quotations. He then printed Paulus’ epitome and Festus side by side, carefully indicating the authorship of each entry ... He reproduced the text of the sole codex of Festus in a most craftsmanlike manner ...

Agustín did not confine himself to reproducing his manuscript. He also proposed a large number of conjectural emendations that are still acceptable, and he elicited suggestions from the other leading scholars in Rome as well ...

To his critical text Agustín added a short commentary. (Grafton 140-143)

Festus’s De Verborum Significatu is valuable not only for what it tells us about the Latin language but also because it quotes extensively from authors whose works have not otherwise survived.

It was only to be expected that Joseph Juste Scaliger should turn his critical gaze upon this work. He was already familiar with Festus, having used him as an important source of rare and archaic words in his own Latin poetry. The subject—archaic Latin and its obscurities—was one that had come to interest him dearly. And what remained of Festus’s work had already been picked over by most of Scaliger’s predecessors, including some of his teachers: Politian, François Baudouin, Louis Le Caron, Barnabé Brisson, Piero Vettori, Carlo Sigonio, Antonio Agustín, Adrien Turnèbe, Willem Canter, Pierre Pithou, Lucas Fruterius, Hadrianus Junius, Hubertus Giphanius, Marc Antoine Muret, and Jacques Cujas. Scaliger rarely let slip the opportunity to pit his philological skills against those of his contemporaries.

Scaliger’s edition of the work of Festus was published in Paris in 1576 with the title:

In Sexti Pompei Festi Libros de Verborum Significatione Castigationes, Recognitae et Auctae

Corrections to the Books on the Meaning of Words by Sextus Pompeius Festus, Revised and Enlarged

Scaliger’s Festus was a product of his last, broken months in Geneva and its environs. In July 1574 he wrote to Pithou from Basel that ‛in the last few days, I have done a little something on Festus, which is already being printed.’ He finished the commentary in September and left it in Geneva with his friend

Goulart, who was to pass it on to the printer. The dedication, dated October 1574, he wrote in France, at the home of the Chasteigners in Abain. And, as the speed with which he worked might lead one to expect, the result was not in fact a new edition of the text. Rather, he followed the same form that he had used for the works of Varro. He reprinted Agustín’s text, wrote a critical and exegetical commentary, and had the two issued together, though they were printed months apart. His conjectures were not introduced into the body of the text. (Grafton 145-146)

Grafton is impressed by the quality of Scaliger’s work:

So far as the commentary proper is concerned, one’s initial impression of Scaliger’'s work is one of prodigal ingenuity and staggeringly broad erudition—a phenomenon that would seem to call for psychological rather than historical explanation.

Again and again Scaliger cut knots that had baffled Agustín ...

Scaliger’s view of Festus’ scholarly attainments was more sceptical and more accurate than Agustín’s ...

More important, Scaliger was simply more ingenious than Agustín. The text was extremely corrupt, and no help could be expected from manuscripts; desperate remedies were needed. Scaliger was both willing and able to burn and cut, and if his desperate scalpel sometimes sank too deep, much of his surgery was curative as well as brilliant. Often he was able to cure by conjecture passages whose wounds Agustín had left untouched ... Again and again, using nothing but Paulus and mother wit, Scaliger rebuilt whole passages that Agustín had left in fragments ...

Fluency in conjecture and attention to detail could hardly be raised to a higher level. (Grafton 146-149)

Scaliger’s assessments of Festus and Verrius Flaccus made a lasting impression on the scholarly world—one which has only recently been modified—and earned him resounding praise from his contemporaries:

Scaliger, then, treated Festus as a grammarian rather than a scholar, and saw his criticisms of Verrius as empty attempts at self-aggrandizement. These views dominated virtually all historical assessments of the De verborum significatu until very recent times; for only after Scaliger wrote was it clear that Festus had drawn exclusively upon Verrius in making his lexicon ...

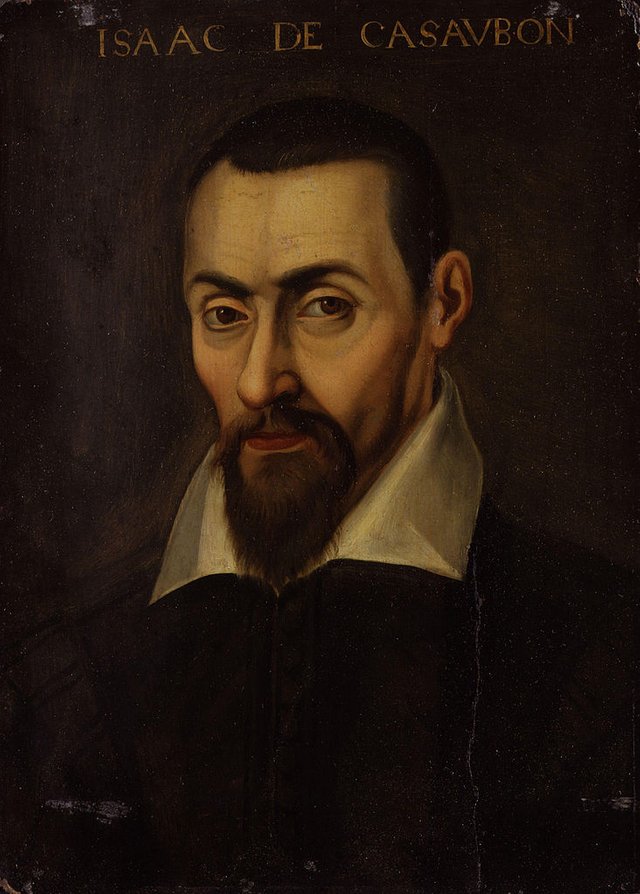

Contemporaries offered a litany of praise to Scaliger’s brilliance and originality. Goulart told Simler that Scaliger had ‛healed Festus miraculously in many passages, filling a great many gaps that had long cried out for Scaliger’s help, and his alone, with his happy dexterity of wit’. Casaubon, marvelling at Scaliger's restoration of the proverb ‛Sabini quod volunt somniant’ [The Sabines can dream what they want], wrote ‛Foelix divinatio et plane divina’ [Happy divination and completely divine] in the margin of his copy . Later, G.J. Vossius would accuse Scaliger of presenting as conjectures what must really have been new variants surreptitiously drawn from manuscripts. Here slander rose to be a curious form of flattery. Vossius could not believe that Scaliger had invented so much that was convincing. At last, Scaliger had found a text that enabled him to make his gifts for composing quasi-antique Latin serve text-critical rather than literary ends. (Grafton 148 ... 149)

One of Scaliger’s innovations was his realization that several compilers of medieval glossaries had drawn directly upon Festus:

This insight was crucial for the establishment of a usable text of Festus, and the way Scaliger pointed has been followed by every subsequent editor, from Fulvio Orsini in 1581 to 1582 to W. M. Lindsay in 1930. Scaliger, keenly aware of his originality, later complained bitterly that Orsini had stolen from him the idea of comparing Festus and the glossaries. (Grafton 151)

Another innovation was his use of a recently discovered manuscript of the Commentary on Virgil by another late Roman grammarian, Servius. The manuscript was discovered by Scaliger’s fellow-philologist Pierre Daniel. This commentary is actually an anonymous expansion of Servius’s original, relatively short, commentary. Scaliger did not have access to the manuscript itself, but Daniel sent him fragments from his forthcoming edition of the commentary, which was not published until 1600. Daniel’s Servius helped Scaliger fill in several gaps in Festus and cast light on many obscurities in the extant text.

There is another side to the story of Scaliger’s Festus, however, which does not redound to Scaliger’s credit. His edition depended heavily upon Agustín’s. Many of the latter’s emendations are repeated by Scaliger without any credit being given to the Spaniard. He also adopted Agustín’s practice of using Paul the Deacon’s epitome to fill in the lacunae in Festus, while at the same time attempting to purge Festus of all of Paul’s interpolations. Scaliger also adopted some of Agustín’s specific arguments without giving him credit:

Here too ambition or egotism blinded him to debts that are obvious to any careful reader. (Grafton 150)

If Grafton is to be believed, there are also two sides to Scaliger’s opinion of his work. Publicly, he was not slow to blow his own trumpet:

Scaliger could indeed congratulate himself on bringing off a tour de force splendidly apposite to the tastes of his contemporaries, with their increasing interest in Tacitus on the one hand and in inscriptions and archaic Latin on the other. No wonder that he spoke in his prefatory letter of excavating venerable monuments from the dust. (Grafton 157)

Grafton, however, argues that, privately, Scaliger was not entirely satisfied with his Festus, and that in the course of his labours he gradually turned away from the French tradition of scholarship in which he had been educated and towards that of the Italians:

Here we see Scaliger struggling to decide between Poliziano and Muret ...

I would not wish to push anyone of these texts too far. Taken together, however, they produce an impression of doubt, of hesitation, almost of bafflement. Certainly Scaliger was no longer satisfied with the methods or the standards in which he had been trained. Even the Festus, a triumph when judged by French standards, gave him qualms. As we shall see, in 1575 a notorious and humiliating contretemps transformed those qualms into convictions of a new kind. (Grafton 160)

The fruits of this new direction did not take long to ripen, as we shall see in the next article.

References

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Joseph Scaliger, In Sexti Pompei Festi Libros de Verborum Significatione Castigationes, Recognitae et Auctae, First Edition, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1576)

- William Smith (editor), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Volume 2, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston (1867)

- Philippe Tamizey de Larroque (editor), Lettres Françaises Inédites de Joseph Scaliger, Alphonse Picard, Paris (1884)

- Aemilius Thewrewk de Ponor [Emil Ponori Thewrewk], Sexti Pompei Festi De Verborum Significatu quae Supersunt cum Pauli Epitome, Academiæ Litterarum Hungaricæ, Budapest, (1889)

- Aemilius Thewrewk de Ponor [Emil Ponori Thewrewk], Codex Festi Farnesianus XLII Tabulis Expressus [Codex Festi Farnesianus Displayed in 42 Plates], Academiæ Litterarum Hungaricæ, Budapest, (1889)

Image Credits

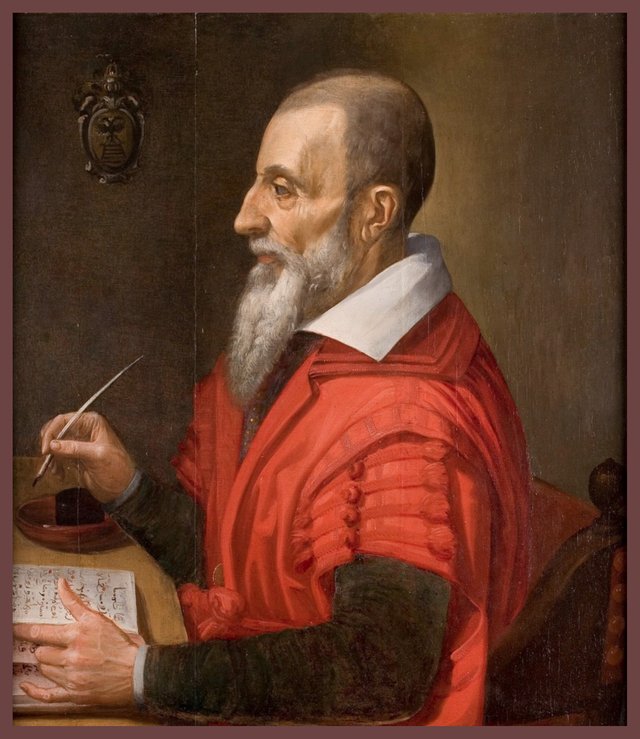

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (Calbet): Antoine Calbet (artist), La Salle des Illustres de l’Hôtel de Ville d’Agen, Agen, Public Domain

- Artist’s Depiction of the Roman City of Narbo: © Jean-Claude Golvin (artist), Fair Use

- Paulus Diaconus: Portrait of Paulus Diaconus, MS Plut. 65.35, Folio 34r, Laurentian Library, Florence, Public Domain

- Codex Festi Farnesianus: Aemilius Thewrewk de Ponor, Codex Festi Farnesianus XLII Tabulis Expressus, Academiæ Litterarum Hungaricæ, Budapest, (1893), Public Domain

- Antonio Agustín y Albanell: José Maea (artist), Francisco Muntaner (engraver), Retratos de los Españoles Ilustres, Real Imprenta de Madrid, Madrid (1791), Public Domain

- Politian: Domenico Ghirlandaio (artist), Tornabuoni Chapel, Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Public Domain

- Anthony Grafton: © The Trustees of Princeton University, Fair Use

- Isaac Casaubon: Anonymous Portrait, National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (Jan Cornelis Woudanus): Jan Cornelis Woudanus (artist), Icones Leidensis, Number 31, Senate Chamber, Academy Building, Leiden University, Public Domain

Online Resources

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Autobiographical Extracts