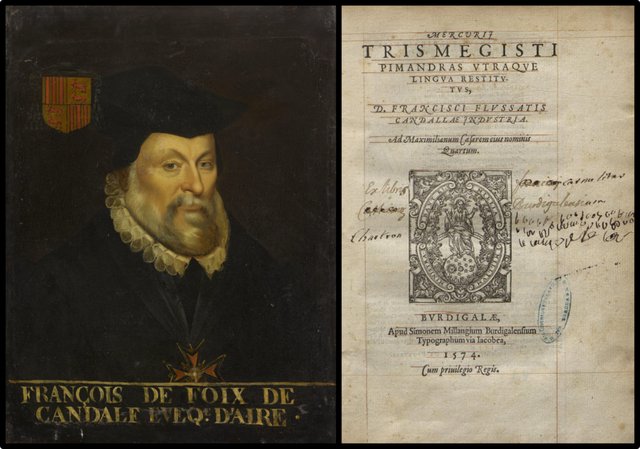

During his brief sojourn in Geneva, Joseph Juste Scaliger contributed in a small way to a number of philological projects undertaken by fellow scholars. The last of these before he returned to France and the protection of Louis de Chasteigner was François de Foix-Candale’s 1574 edition of the Corpus Hermeticum. This collection of philosophical and theological treatises comprises part of the Hermetica, a body of occult tracts traditionally attributed to the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus.

Many scholars of Christendom regarded Hermes Trismegistus as an historical figure: a wise Egyptian priest, who lived in the time of Moses and who foresaw the coming of Christianity. Among these were Lactantius, Saint Augustine, Marsilio Ficino, Tommaso Campanella, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, and Giordano Bruno. In Scaliger’s day, however, there were some skeptics who were beginning to suspect that the Corpus Hermeticum was a collection of relatively late works. In 1614, Scaliger’s colleague Isaac Casaubon published a devastating critique of the Corpus, proving that it had been compiled after the rise of Christianity. Scaliger and Casaubon were frequent correspondents, though they never met. Scaliger once described Casaubon as the greatest man we have in Greek (Desmaizeaux 259).

The Hermetica comprise more than two dozen works in Greek, Latin and Arabic on a variety of subjects: astrology, medicine, pharmacology, alchemy, magic, religion, theology, philosophy, cosmology, and anthropology. Out of these, the Corpus Hermeticum comprises seventeen or eighteen Greek tracts on religious and philosophical subjects. These were written anonymously sometime between 100 and 300 CE and compiled into a single collection by later Byzantine editors.

In 1459 a manuscript of the first fourteen tracts of the Corpus Hermeticum was discovered in Macedonia by the Christian monk Leonardo da Pistoia (Leonardo Alberti de Candia). The following year, he brought it back to Italy and presented it to his patron Cosimo de’ Medici, Lord of Florence. In 1463 Cosimo ordered the humanist scholar Marsilio Ficino to interrupt his ongoing translation of the complete works of Plato in order to translate this newly rediscovered work of Hermes Trismegistus. Ficino’s Latin translation of these fourteen tracts was published in Treviso in 1471 by Gerhard von Lisa. Ficino named the collection Pimander, after the spiritual guide who delivers the opening discourse. Ficino’s manuscript is now in Florence’s Laurentian Library (Cod. Laur. 71,33 s. XIV). The manuscript is officially dated to the 14th century (s. XIV), but some online sources I consulted claim that it had originally belonged to the Byzantine scholar Michael Psellos, who lived in the 11th century.

Tracts 16-18 were first translated into Latin by the Italian hermeticist Lodovico Lazzarelli in 1482. Lazzarelli had discovered these three tracts in a manuscript unknown to Ficino (Hanegraaff 680). The 15th tract, however, was missing from the manuscripts used by Ficino and Lazzarelli.

In 1554 Adrien Turnèbe brought out a new edition of the Corpus Hermeticum, comprising the Greek text, Ficino’s Latin translation of the first fourteen tracts, and brief commentaries on each of these. For the missing 15th tract Turnèbe substituted three excerpts from the Hermetica preserved by the 5th-century Macedonian scholar Johannes Stobaeus. The 18th tract had been exposed as a later addition by Michael Psellos, but Turnèbe included it in his edition (Copenhaver xl-xli). The Latin translations of tracts 15-18 are those made by Lodovico Lazzarelli (Yates 173). The Cretan copyist Angelo Vergecio wrote the Greek preface.

François de Foix-Candale’s 1574 edition of the Corpus Hermeticum comprised the Greek text of the first sixteen tracts from Turnèbe’s 1554 edition, emended by Joseph Scaliger, and a new Latin translation by de Foix-Candale. He also included the three extracts from Stobaeus as a substitute for the 15th treatise. To these he added the entry on Hermes Trismegistus in the Byzantine encyclopaedia known as the Suda. Angelo Vergecio had drawn on this entry in his Greek preface to Turnèbe’s edition. De Foix-Candale’s edition conflates the 17th tract with the 14th, and omits the 18th tract altogether (Nelson xii).

The numbering of the eighteen tracts in modern editions follows de Foix-Candale. The titles are those of G R S Mead’s translation:

- Poimandres, The Shepherd of Men

- Hermes to Asclepius

- The Sacred Sermon

- The Cup or Monad

- Though Unmanifest, God Is Most Manifest

- In God Alone Is Good and Elsewhere Nowhere

- The Greatest Ill among Men Is Ignorance of God

- That No one of Existing Things Doth Perish

- On Thought and Sense

- Of Thrice-Greatest Hermes

- Mind onto Hermes

- About the Common Mind

- The Secret Sermon on the Mountain

- A Letter of Thrice-Greatest Hermes to Asclepius

- Extracts from Johannes Stobaeus and the Suda

- The Definitions of Asclepius unto King Ammon

- Asclepius to King Ammon

- The Encomium of Kings

In his preface, de Foix-Candale briefly acknowledges his debt to Scaliger in emending the Greek text—patching a few errors in the painter’s canvas— and in elucidating some words in the oriental languages:

(utpote Iosephi Scaligeri, iuvenis illustrissimi, non minus doctis linguis eruditi, quam conditione et prosapia praeclari, opera)

(the work, namely, of Joseph Scaliger, a most illustrious young man, who is no less erudite in learned languages than he is illustrious in rank and lineage) ... (de Foix-Candale Folio v)

Scaliger’s Contributions

What was the extent of Scaliger’s contributions to this project? He is probably responsible for most if not all of the marginal notes, which emend the Greek text published by Scaliger’s former teacher Adrien Turnèbe. The Latin translation, however, is thought to be by de Foix-Candale alone:

Scaliger helped de Foix de Candale establish the Greek text underlying his Latin version and determine the meaning of the strange locutions that occurred in this Greek text supposedly translated long ago from Egyptian hieroglyphs. It was probably Scaliger, for example, who argued that Hermes, in writing to his son Tat, had deliberately used that form in place of the ‛true Greek name Hermes’, and drew the conclusion that ‛Mercury acted as his own Greek translator. For another Greek would hardly have silently omitted Mercury’s true name, Hermes, in order to confer on the son Tat the father’s Egyptian name Thoth. (Grafton 67, de Foix-Candale fol v-vi, Parthey xvi)

De Foix-Candale was convinced of the historicity and antiquity of Hermes Trismegistus and of the authenticity of the works attributed to him:

De Foix de Candale tried to date the Corpus ... He insisted that Hermes, as the founder of Egyptian culture, must have lived long before Moses ... In particular, he identified Hermes Euhemeristically as the son of Saturn, who flourished in the time of Abraham’s successor Sarug. Hermes, then, had lived at the very beginning of human history after the Flood. (Grafton 67)

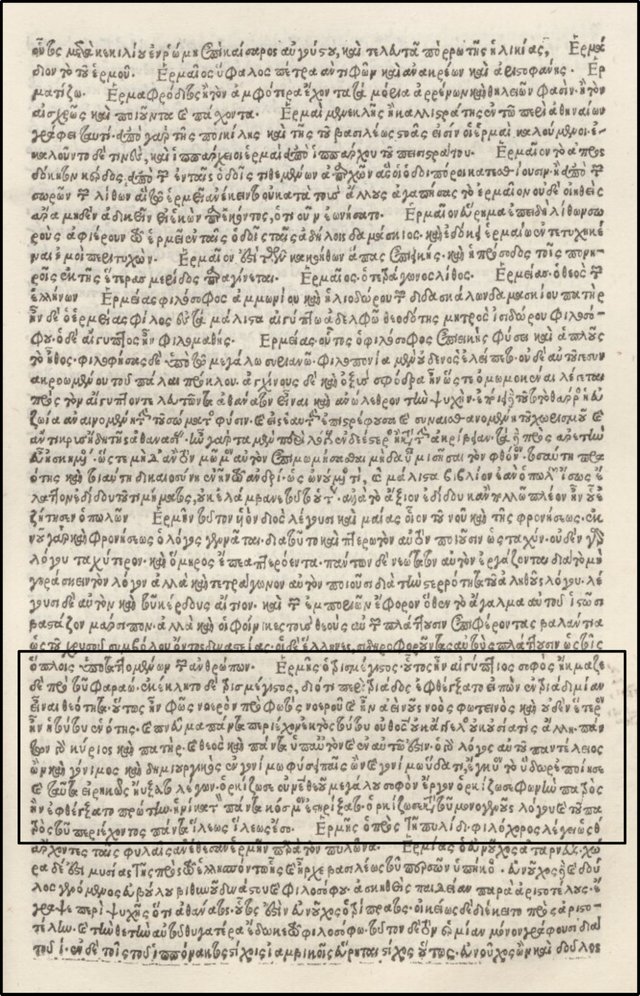

De Foix-Candale was guided to these conclusions by the entry on Hermes Trismegistus in the Suda:

This man was an Egyptian sage; he flourished before the Pharaoh. He was called Trismegistos [Thrice-Great] because he made a statement about the triad [or trinity], saying [that] a single deity exists in triadic form thus: “There existed an intellectual light prior to the intellectual light, and there was always a mind enlightening the mind, and its unity was nothing else; and it was a spirit containing everything. Apart from that there did not exist another god, or angel, or essence. Because he is lord and father and god of everything, and everything is under him and within him. For his word being complete and fruitful and creative, and being a child in fruitful nature and fruitful water, he made the water pregnant.” And having said these things, he prayed: “I adjure you, sky, wise creation of the great god; I adjure you, voice of the father, the one that he spoke first, when he firmly set the whole world; I adjure you, by his only-begotten word and by the father who contains everything, gracious, be gracious.” (Suda ε 3038)

It would be interesting to know how far Scaliger agreed with de Foix-Candale, and the extent to which the latter’s opinions were influenced by him. We do know from the Scaligerana, however, that Scaliger accepted the historicity and antiquity of Hermes Trismegistus:

Philo Judaeus is a wonderful author and well worth reading. More wonderful still, and very ancient, is Pimander Mercurius Trismegistus. (Desmaizeaux 136, Grafton 67)

The Suda’s entry on Hermes was drawn partly from the Chronographia of the Byzantine scholar John Malalas, who flourished in the 6th century. Scaliger, of course, would later devote himself to the study of chronology and chronography, but Grafton speculates that at this point in his career he was not aware of the sources the author of the Suda had drawn upon:

What de Foix de Candale and Scaliger did not say—and may not have known—was that their evidence for Hermes’ antiquity also came from the tradition of chronographic scholarship ... Scaliger and de Foix de Candale, in other words, used the methods and results of Byzantine chronological scholarship without knowing that they did so. (Grafton 69).

All in all, Scaliger’s contributions to François de Foix-Candale’s Corpus Hermeticum were not deemed sufficient to earn him more than a single parenthetical mention.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Brian P Copenhaver, _ Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction_, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1992)

- Pierre Desmaizeaux (editor), Scaligerana, Thuana, Perroniana, Pithoeana, et Columesiana, Volume 2, Prima Scaligerana, Secunda Scaligerana, Covens & Mortier, Amsterdam (1740)

- Marsilio Ficino, Mercurii Trismegisti Liber de Potestate et Sapientia dei e Graeco in Latinum Traductus a Marsilio Ficino Pimander Incipit, Gerhard von Lisa, Treviso (1471)

- François de Foix-Candale (editor), The Pimander of Hermes Trismegistus, Greek Text and Latin Translation by Adrien Turnèbe (1554), Simon Milanges, Bordeaux (1574)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Wouter J Hanegraaff (editor) Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Brill, Leiden (2006)

- George Robert Stow Mead (translator), Thrice Greatest Hermes, Volume 2, Sermons, The Theosophical Publishing Society, London (1906)

- David Wulstan Myatt (translator), Poemandres: A Translation and Commentary, DW Myatt, Online (2013)

- Jane Everingham Nelson, Shakespeare and Religio Mentis, Brill, Leiden (2022)

- Gustav Parthey (editor), Hermetis Trismegisti Poemander, Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin (1854)

- Adrien Turnèbe, Mercurii Trismegisti Pœmander, Seu De Potestate et Sapientia Dei, Guillaume Morel, Paris (1554)

- Frances A Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London (1964)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Nicolas Eustache Maurin (painter), François-Séraphin Delpech (engraver), Bibliothèque de Genève, Public Domain

- François de Foix-Candale: Anonymous Portrait, Palace of Versailles, Public Domain

- Adrien Turnèbe: Anonymous Engraving, Alfred Gudeman, Imagines Philologorum, Page 7, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1911), Public Domain

- Marsilio Ficino: Domenico Ghirlandaio (artist), Tornabuoni Chapel, Florence, Public Domain

- Hermes Trismegistus: Johann Theodor de Bry (engraver), Jean-Jacques Boissard, Tractatus Posthumus de Divinatione et Magicis Præstigiis, Page 1, Hieronymus Galler, Oppenheim (1615), Biblioteca Nacional de España, Public Domain.

- Anthony Grafton: © The Trustees of Princeton University, Fair Use

- Suda Entry for Hermes Trismegistus (Editio Princeps): Demetrius Chalcondyles (editor), Suda, Johannes Bissolus & Benedictus Mangius, Milan (1499), Public Domain

Online Resources