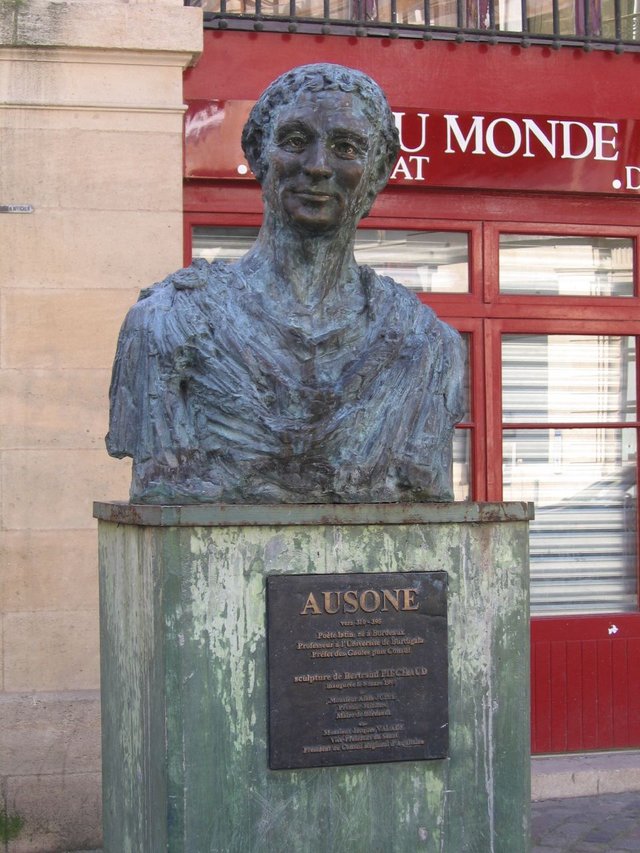

During his two years in Geneva (1572-74), Joseph Juste Scaliger undertook several philological projects. One of these, his study of the Astronomica by Marcus Manilius, would not be ready for the printer until 1579. Of the others, the first to be completed was an edition of the works of Decimius Magnus Ausonius, a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric who flourished in the 4th century of the Common Era. Like Scaliger, Ausonius was a native of Aquitania. He was born around 310 CE in Bordeaux, where Scaliger received his only formal schooling. He was educated at Bordeaux, and later under the tutelage of his uncle Aemilius Magnus Arborius at Toulouse. In 328 Arborius was summoned to Constantinople to become tutor to one of the sons of the Emperor Constantine the Great—apparently either the future Constantine II or Constantius II, who held the office of Caesar at that time—whereupon Ausonius returned to Bordeaux to complete his education under the rhetorician Minervius Alcimus.

In 334 Ausonius became a teacher of rhetoric at a school in Bordeaux, a position he held for thirty years. In 364, the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian I appointed him as tutor to his son and heir Gratian, who was then about five years old. He and Gratian accompanied Valentinian during the German Campaign of 368-369. In 370 the title of comes was conferred upon him, and five years later he became quaestor sacri palatii (a sort of Attorney General to the Emperor).

Gratian became Western Roman Emperor in 375, when he was only sixteen and still under the tutelage of Ausonius. Like his father, he repaid the services of the old man with titles and honours. In 377 Ausonius was made Praetorian Prefect of Italy. The following year he became Praetorian Prefect of Gaul. In the same year he took part in Gratian’s campaign against the Lentienses, an Alemannic tribe, in Germany. During this campaign his share of the booty included a slave-girl, Bissula, to whom he later addressed one of his poems. His father Julius Ausonius was given the rank of Prefect of Illyricum when he was nearly ninety years old, and his son Hesperius was made Proconsul of Africa in 376. Finally, Ausonius was appointed Consul—the Empire’s highest political office—for the year 379 CE.

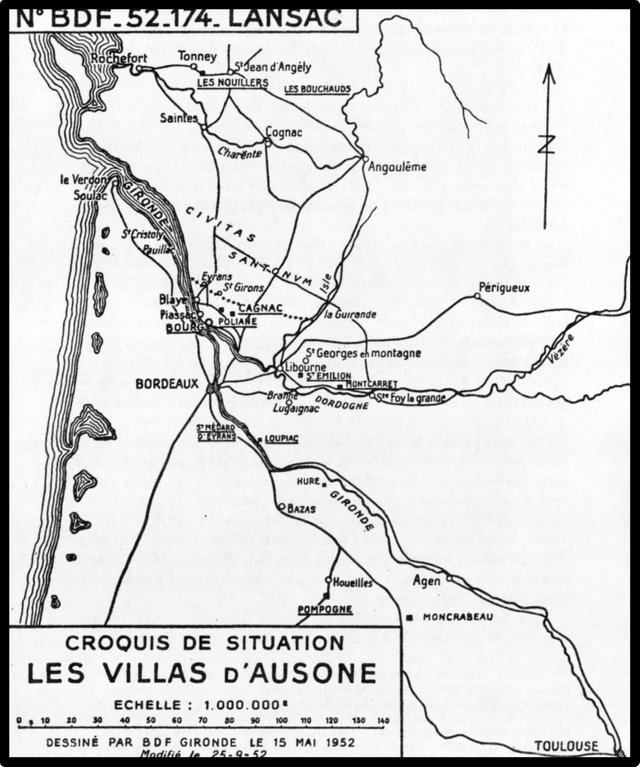

When Gratian was assassinated by Magnus Maximus’s Master of the Horse at Lyon in 383, Ausonius was permitted to retire to his estates near Bordeaux. Château Ausone, near Saint-Émilion, takes its name from Ausonius in the belief that one of his estates was located here, about 30 km east of Bordeaux. Another town in this region, Lugaignac, which is situated about 9 km south of Saint-Émilion, has been identified with another of Ausonius’s estates, Lucaniacum. Whichever of his estates he retired to, Ausonius spent the remaining years of his life in this nidus senectutis (nest of my old age), composing poetry and corresponding with former pupils. Among these was Paulinus, the Bishop of Nola, who may have been instrumental in convincing Ausonius to convert to Christianity.

Ausonius died around 395, at the age of about eighty-five. The precise years of his birth and death are not known.

Extant Works of Ausonius

The poetry of Ausonius was admired in his day, but it has not stood the test of time. In his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon delivers the following withering comments in his footnotes:

Valentinian was less attentive to the religion of his son [ie Nicene Christianity]; since he intrusted the education of Gratian to Ausonius, a professed Pagan. (Mémoire de l’Académie des Inscriptions, Tome 15, Pages 125-139). The poetical fame of Ausonius condemns the taste of his age ...

Ausonius was successively promoted to the Prætorian præfecture of Italy (a.d. 377) and of Gaul (a.d. 378); and was at length invested with the consulship (a.d. 379). He expressed his gratitude in a servile and insipid piece of flattery (Actio Gratiarum, p. 699), which has survived more worthy productions. (Gibbon, Chapter 27, Footnotes)

In the eleventh Edition of The Encyclopædia Britannica, the anonymous author of the article on Ausonius sums up his work thus:

Ausonius was rather a man of letters than a poet; his wide reading supplied him with material for a great variety of subjects, but his works exhibit no traces of a true poetic spirit; even his versification, though ingenious, is frequently defective. (The Encyclopædia Britannica 2:935-936)

Hugh G Evelyn White, who translated the works of Ausonius for the Loeb Classical Library, delivered this appraisal of his worth:

The place to be assigned to Ausonius as a poet is not a high one. He lacked the one essential, the power of penetrating below the surface of human nature; indeed his verse deals rather with the products of man than with mankind itself. His best quality, appreciation for natural and scenic beauty, is rarely indulged; and this, after all, is an accessory, not an essential, of poetry. In his studies of persons (such as the Parentalia and Professores) he gives us clever and sometimes striking sketches, but never portraits which present the inner as well as the outer man. (White I:xxxiv)

Finally, in William Smith’s A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, the English physician and Classical scholar William Alexander Greenhill writes:

His poetical powers have been variously estimated. While some refuse to allow him any merit whatever, others contend that had he lived in the age of Augustus, he would have successfully disputed the palm with the brightest luminaries of that epoch. Without stopping to consider what he might have become under a totally different combination of circumstances, a sort of discussion which can never lead to any satisfactory result, we may pronounce with some confidence, that of all the higher attributes of a poet Ausonius possesses not one. Considerable neatness of expression may be discerned in several of his epigrams, many of which are evidently translations from the Greek; we have a very favourable specimen of his descriptive powers in the Mosella, perhaps the most pleasing of all his pieces; and some of his epistles, especially that to Paulinus (xxiv.) are by no means deficient in grace and dignity. But even in his happiest efforts we discover a total want of taste both in matter and manner, a disposition to introduce on all occasions, without judgment, the thoughts and language of preceding writers, while no praise except that of misapplied ingenuity can be conceded to the great bulk of his minor effusions, which are for the most part sad trash. His style is frequently harsh, and in latinity and versification he is far inferior to Claudian. (Smith )

The following are the extant works of Ausonius—after White, and Rudolf Peiper’s 1886 edition (Teubner, Leipzig). Peiper arranged Ausonius’s works into 23 Books (the last three comprising spurious works) under the general title Opuscula (Short Works):

| Book | Latin | English | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Praefatiunculae | Prefatory Pieces | Prefaces by the poet to various collections of his poems, including a response to the Emperor Theodosius I’s request for his poems |

| II | Ephemeris | The Doings of a Whole Day | A description of the occupations of the day from morning till evening, in various meters, composed before 367. Only the beginning and end are preserved. |

| III | Domestica | Personal Poems | Six personal poems |

| IV | Parentalia | Parentalia | 30 poems of various lengths, mostly in elegiac meter, on deceased relations, composed after his consulate (379), when he had already been a widower for 36 years. |

| V | Professores | Professors of Bordeaux | A continuation of the Parentalia, commemorating famous teachers of his native Bordeaux whom he had known |

| VI | Epitaphia | Epitaphs | 26 epitaphs of heroes from the Trojan war, translated from Greek (and 9 others that are probably spurious) |

| VII | Eclogarum Liber | Eclogues | A collection of all kinds of astronomical and astrological versifications in epic and elegiac meter |

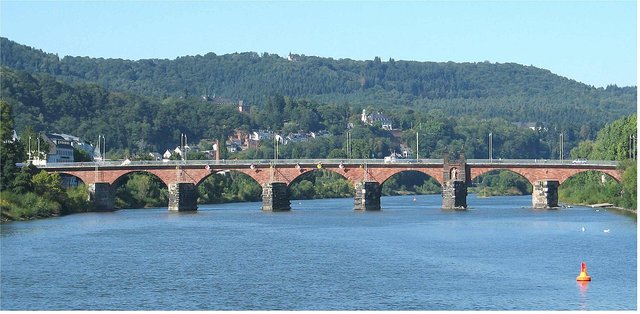

| VIII | Cupido Cruciatur | Cupid Crucified | Verses inspired by a painting at Trèves |

| IX | Bissula | Bissula | Verses in honour of Ausonius’s slave girl |

| X | Mosella | The Moselle | Ausonius’s tribute to the River Moselle, which flowed through Trèves (Trier), the capital of the western provinces |

| XI | Ordo Urbium Nobilium | The Order of Famous Cities | 14 pieces dealing with 20 cities of the Empire, in hexameters, and composed after the downfall of Maximus in 388 |

| XII | Technopaegnion | The Game of Skill | A set of poems in which each verse ends in a monosyllable |

| XIII | Ludus Septem Sapientum | The Masque of the Seven Sages | A kind of puppet play in which the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece appear successively and have their say. Another short collection, Septem Sapientum Sententiae (Sayings of the Seven Sages) has also been attributed to Ausonius, but is generally considered spurious. It replaces Thales of Miletus with Anacharsis the Scythian. |

| XIV | Caesares | The Twelve Caesars | Verses on the Twelve Caesars described by the biographer Suetonius Tranquillus |

| XV | Fasti | The Book of Annals | Originally a list of the kings and consuls of Rome from the foundation of the city down to Ausonius’s own consulate. Only the concluding addresses are extant. |

| XVI | Griphus Ternarii Numeri | A Riddle on the Number Three | A celebration of the universality of the mystic number three, written during the Alemannic War in 368 |

| XVII | Cento Nuptialis | A Nuptial Cento | An epithalamium comprising quotations from Virgil, written during the Alemannic War in 368 |

| XVIII | Epistolarum liber | Epistles | 35 verse letters in various meters |

| XVIX | Epigrammata | Epigrams | 112 epigrams on various subjects |

| XX | Gratiarum Actio ad Gratianum | Thanksgiving to the Emperor Gratian | Prose speech of thanks to the Emperor Gratian on the occasion of attaining the consulship, delivered at Trèves in 379 |

| XXI | Periochae Homeri Iliadis et Odyssiae | Summaries of the Iliad and the Odyssey | Spurious prose summaries |

| XXII | Appendix Ausoniana | Appendix to Ausonius | 10 spurious poems |

| XXIII | Epigrammata et Carmina | Epigrams and Songs | 36 spurious epigrams and songs |

Mention might also be made of the so-called Idyllia or Edyllia, an anthology of twenty pieces by Ausonius that must have been compiled sometime during the Middle Ages, as the collection can be found in some early manuscripts. It is possible, however, that Edyllia is an error for the Greek Epyllia, meaning versicles, or short poems.

Scaliger and Ausonius

Joseph Scaliger’s interest in Ausonius dates from the time he spent in study with the French jurist Jacques Cujas at Valence between 1570 and 1572:

Cujas, whose generosity with his books was proverbial, threw open his library to Scaliger. In this great collection there were no fewer than two hundred manuscripts of texts of every kind. Scaliger, so Cujas pretended to complain, ‛deflowered them’. He used manuscripts of Martial, Priscian, Dositheus, and Victorinus. He copied Cujas’s manuscript of the Satyricon of Petronius, which is now lost, but was more complete and accurate than those that have survived. In 1572, when Élie Vinet asked Scaliger and Cujas to speed up the printing of his [Vinet’s] edition of Ausonius, Scaliger took the opportunity to collate Cujas’s great Ausonius manuscript, a ninth-century codex in Visigothic script. (Grafton 122)

As a boy, Scaliger had studied under Vinet at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux.

The 9th-century manuscript—usually denoted V by modern philologists—is now in Leiden University Library, catalogued as MS Voss. Lat. fol. 111. Scaliger entered his collation in a copy of Theodor Poelman’s edition of Ausonius (Antwerp, 1568), which is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

Scaliger resumed his work on Ausonius in Geneva and brought it to a completion in the summer of 1573. It was inevitable that Scaliger would tackle Ausonius sooner or later. The intellectual challenge his work presented and the opportunities it offered for scholarly glory were too enticing to an ambitious and vain man like Scaliger:

This work, more than any of the others from this period, represented a clear attempt to apply Cujas’s method to the criticism of a classical text. Ausonius had long interested philologists. This quirky late Roman aristocrat, who wrote Latin and Greek with equal facility, rewarded those diligent enough to plough through his works with vast amounts of historical, geographical, mythological, and even scientific information. Construing him had much of the fascination of completing a difficult crossword puzzle; sometimes, indeed, he deliberately wrote in riddles. Humanists from Poliziano onwards had tried their hand at parts of his work. In 1556 or 1557, moreover, a new manuscript of Ausonius had been discovered by Étienne Charpin [Stephanus Charpinus]; and in 1558 an edition of some of the new material from it appeared at Lyons. It was poorly edited; much of the new material, in particular, was incomprehensible or nearly so. Accordingly, every major French philologist tried, either by gaining access to the new manuscript or by devising conjectures, to improve passages. Pithou, Turnèbe, and Canter each took a hand in the game. Finally, Élie Vinet of the Collège de Guyenne managed to borrow the manuscript from Cujas, into whose collection it had come. By 1567 he had completed a new edition, which he sent to Gryphius in Lyons for publication. (Grafton 128)

Antonius Gryphius delayed printing Vinet’s edition for several years, and, as we have seen, Vinet wrote to Cujas and Scaliger in 1572 to see if they could intervene with Gryphius on his behalf. Scaliger had by then become acquainted with several of Vinet’s conjectures through a mutual friend Jacques Salomon, a lawyer from Narbonne. He wrote to Vinet informing him that he approved of them, and several eventually made their way into his own edition of Ausonius. Vinet’s edition finally came out in 1575, one year after Scaliger’s. The two men remained in contact, however, until Vinet’s death in 1587. Scaliger’s epitaph on Vinet’s scholarship was generous:

That the two men remained friends is a testament to Vinet’s complaisance. According to Anthony Grafton, far from pushing Vinet’s edition of Ausonius through the press, Scaliger essentially hijacked it and refashioned it in his own hand:

Instead of merely fulfilling Vinet’s request, he evidently decided to rework the edition completely. He made an independent collation of Cujas’s manuscript, which he entered in the margins of a copy of Poelman’s 1568 Plantin edition. And in the summer of 1573, while at Basel, he completed his revised version and dedicated it—with considerable effrontery—to Vinet, who then abandoned all hope of printing his edition in Lyons and set out to prepare an even more polished version, which he eventually published at Bordeaux. (Grafton 129)

Ausonianae Lectiones

Scaliger’s edition of the works of Ausonius comprises a lengthy commentary—including Scaliger’s own brief Life of Ausonius—and a selection of Ausonius’s works. The commentary, in two books, comprises about 180 pages. The 33rd and final chapter of Book 2 is Scaliger’s Life of Ausonius, which only takes up about five pages. Over three hundred pages are given over to the selections from Ausonius:

| Page | Contents |

|---|---|

| 1 | Epigrammata |

| 37 | Ephemeris |

| 45 | Parentalia |

| 63 | Professores |

| 85 | Epitaphia |

| 95 | Caesares |

| 102 | Ordo Nobilium Urbium |

| 109 | Ludus Septem Sapientum |

| 121 | Versus Paschales |

| 123 | Epicedium in Patrem |

| 125 | Villula |

| 127 | Protrepticus |

| 130 | Genethliacon |

| 132 | Cupido Cruci Affixus |

| 137 | Bissula |

| 138 | Precatio Consulis Designati |

| 141 | Mosella |

| 160 | Griphus Ternarii Numeri |

| 163 | Technopægnion |

| 174 | Cento Nuptialis |

| 181 | Rosæ |

| 183 | Vita Humana |

| 185 | Vir Bonus |

| 186 | Ναὶ καὶ οὐ Πυθαγορικόν [The Pythagorean Yes and No] |

| 187 | Aetates Animalium |

| 188 | Herculis Labores |

| 188 | Musarum Inventa |

| 189 | De Ratione Libræ |

| 190 | De Ratione Puerperii Maturi |

| 191 | Signa Cælestia |

| 192 | Ratio Dierum Anni Vertentis |

| 198 | De Feriis Romanis |

| 200 | De Agonibus, et Alia |

| 201 | Epistolae: Ad Patrem |

| 202 | Epistolae: Ad Filium |

| 203 | Epistolae: Ad Hesperium |

| 204 | Epistolae: Ad Theonem |

| 212 | Epistolae: Ad Axium Paulum Rhetorem |

| 220 | Epistolae: Ad Tetradium |

| 221 | Epistolae: Ad Probum Præfectum Prætorio |

| 226 | Epistolae: Ad Symmachum |

| 229 | Epistolae: Ad Ursulum Grammaticum |

| 230 | Epistolae: Ad Pontium Paulinum |

| 248 | Gratiarum Actio |

| 273 | Periochae Rhapsodiarum Homeri |

| 291 | Quinti Symmachi Epistolæ ad Ausonium |

| 307 | Pontii Paulini Literæ Ausonio Rescriptæ |

| 320 | Eiusdem Paulini Literæ ad Gestidium, et Oratio ad Deum |

| 322 | Sulpiciae Carmen de Temporibus |

| 325 | Cytherii Sidonii Epigramma de Tribus Pastoribus |

| 325 | Hadriani Imperatoris de Tribus Amazonibus |

| 326 | Oratio Paschalis Versibus Rhopalicis |

The world of Ausonius was the Gaul of the late Roman Empire, and Scaliger appreciated that whatever their literary merits, the works of Ausonius were a rich source of the lost history of this region. That Scaliger himself was a native of this region only enhanced the interest he took in this minor figure. His chief contributions to the study of Ausonius were not his emendations and conjectures on the texts but his commentaries on their contents:

... he drew in his commentary on every source to which Cujas had led him in order to bring Ausonius’ world back to life. To correct and identify the vast number of place-names in Ausonius’ Mosella he used inscriptions, many of which he had copied in the course of his own journey from Southern France to Geneva! He supplemented them with the findings of other antiquaries who had studied the topography of late antique Gaul ... Beatus Rhenanus ... the Notitia Imperii Romani ... Sulpicius Severus ... an unpublished account of Priscillian’s conduct at the Synod of Bordeaux ... a constitution by the Emperor Constantine III ... the Hermeneumata Pseudo-Dositheana ... Casaubon rightly described Scaliger’s work as a study in the reconstruction of late antique history and topography ... Clearly Scaliger had mastered the non-literary sources which had long been a chief province of the humanistic jurists. (Grafton 131)

Scaliger’s appreciation of Ausonius’ literary merits may have been coloured as much by a sense of national pride as by his assessment of his own standing as a literary specialist in the Parisian mould (Grafton 130). Ausonius was a fellow Aquitanian, and to attack him was to attack Scaliger:

We must not be worried about those who do not like this poet. For they are the same ones who say that the Garonne is a little stream, Bordeaux a hamlet, Aquitaine itself no more than an ordinary diocese; they speak of the very Senate of Bordeaux as no more than a division of a town council. Can you stop yourself from laughing when you hear them say these things? ... And yet one hears them not from the ordinary crowd but from those who hold high office, who enjoy great prominence, who wish to have literary reputations ... We are neither sharp-witted nor completely obtuse; and if those important men are willing to abandon a bit of their pride, we can teach them both what Aquitaine is and what it is to be a critic in literature. (Ausonianae Lectiones 5-6, translated by Grafton 132)

Scaliger’s Ausonianae Lectiones was published in Lyon in 1574 by Antoine Gryphe, the son and successor of Sébastien Gryphe.

Critique of the Ausonianae Lectiones

Grafton is lukewarm in his appraisal of this work. To begin with, Scaliger’s scholarship suffered from his impatience to be done with the work:

Both text and commentary of the Ausonius suffered from serious defects. Though now middle-aged, Scaliger was still in a hurry ... Scaliger’s collation of his manuscript, though accurate as far as it went, was hurried and incomplete. Sometimes he corrected the titles of poems against the manuscript, sometimes not. (Grafton 129)

He also adopted many of Vinet’s emendations without giving credit to Vinet, a practice he never failed to condemn when he was the victim of it (Grafton 129).

In Grafton’s opinion, the works of Ausonius were far from ideal for displaying the philological skills Scaliger had acquired after fifteen years of study at Paris, Valence, Geneva and elsewhere:

What he needed was a text central to the classical culture of his time and appropriate for his new historical approach. He found it in one of the most difficult, corrupt, and controverted works in Latin prose: the De verborum significatu of Festus. (Grafton 132)

And it was to Festus that Scaliger next turned, before the end of his short sojourn in Geneva.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1910)

- Pierre Desmaizeaux (editor), Scaligerana, Thuana, Perroniana, Pithoeana, et Columesiana, Volume 2, Prima Scaligerana, Secunda Scaligerana, Covens & Mortier, Amsterdam (1740)

- Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 2, The Modern Library, Random House, Inc, New York (1946)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Rudolf Peiper (editor), Decimi Magni Ausonii Burdigalensis Opuscula, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1886)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (editor), Ausonianae Lectiones [Decimius Magnus Ausonius: Selections from His Works], Antoine Gryphe, Lyon (1574)

- William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1890)

- Hugh G Evelyn White (translator), Ausonius, Volume 1, William Heinemann, London (1919)

- Hugh G Evelyn White (translator), Ausonius, Volume 2, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1985)

- Payson Sibley Wild, Ausonius: A Fourth Century Poet, The Classical Journal, Volume 46, Number 8, Pages 373-382, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (1951)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Nicolas Eustache Maurin (painter), François-Séraphin Delpech (engraver), Bibliothèque de Genève, Public Domain

- Bust of Ausonius in Bordeaux: Bertrand Piéchaud (sculptor), © dizzymissytrolly (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Emperor Gratian: Roman Solidus from the Reign of Gratian, © Rasiel Suarez (photographer), Public Domain

- Edward Gibbon: Joshua Reynolds (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- Bordeaux in 1572: Georg Braun, Franz Hogenberg & Simon Novellanus, Beschreibung und Contrafactur der vornembster Stät der Welt (Band 1), Book 1, Page 10v, Köln (1582), Public Domain

- The Roman Bridge over the Moselle at Trèves: © Johnny Chicago (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Élie Vinet: Supposed Portrait of Élie Vinet, in Gaston Chevrou, A la Mémoire du Saintongeais Élie Vinet, Public Domain

- Scaliger on Élie Vinet: Antoine Calbet (artist), La Salle des Illustres de l’Hôtel de Ville d’Agen, Agen, Public Domain

- Château Ausone (Saint Émilion): © Château Ausone / Studio Pomelo, Fair Use

- Ausonius’s Estates near Bordeaux: © Pierre Grimal, Les Villas d’Ausone, Revue des Études Anciennes Année, Volume 55, Numbers 1-2, Pages 113-125, Swets & Zeitlinger, Amsterdam (1953), Fair Use

Online Resources

- The Warburg Institute

- Leiden University Libraries

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Autobiographical Extracts