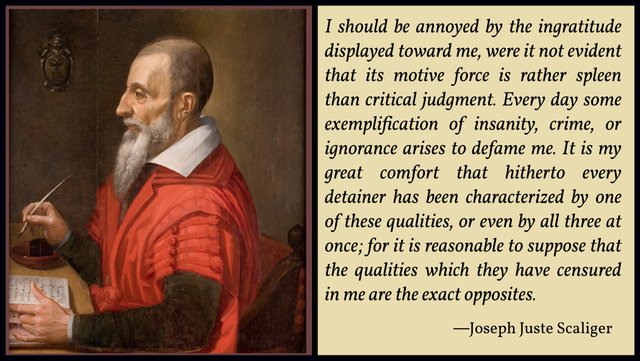

Joseph Juste Scaliger never wrote an autobiography, but an autobiography of sorts has been compiled from passages scattered throughout his extensive correspondence, supplemented by his last will and testament and by the funeral orations delivered by his colleagues Daniel Heinsius and Dominicus Baudius. In 1927, Harvard University Press brought out an English translation of these extracts by George W Robinson. This “autobiography”, however, should be taken with a grain of salt. Even Anthony Grafton, the leading Scaligerian scholar of our age, describes it as inaccurate and tendentious:

Yet it has set the lines along which most treatments of Scaliger have proceeded for centuries. Few scholars have questioned its basic accuracy of tone. No one has subjected its fact content to the normal touchstones of historical criticism. And some of the rhetoric it has evoked from its later readers ... suggests that the attention devoted to its author has often been neither historical nor biographical, but hagiographical. (Grafton 1988:584)

Nevertheless, with the help of these biographical passages, scholars have been able to trace the origins of Scaliger’s literary output.

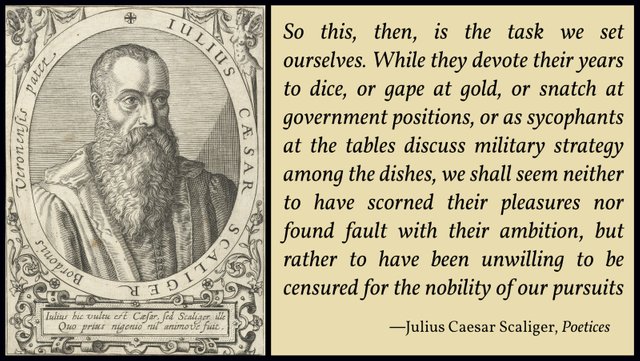

Joseph Juste Scaliger was born on 5 August 1540 [Old Style] at Agen, in Guienne, a large province in the south of France. His father was the Italian Classical scholar Julius Caesar Scaliger. As a child, he received little formal schooling:

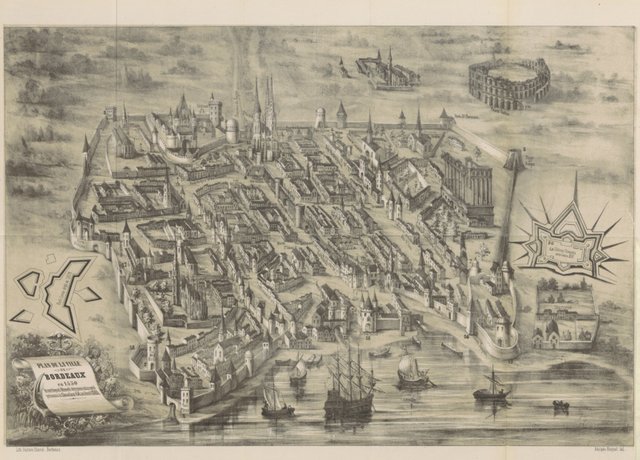

When I was eleven years old, my father sent me to Bordeaux, in company with my brothers, Leonard and John Constant. There for three years I studied the rudiments of Latin. The plague then compelling my departure from the city, I returned to my father. (Robinson 29)

From June 1552 to July 1555, Joseph and his brothers attended the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux. Letters from the boys’ tutors to their father have survived and were published by Pierre Jules de Bourrousse de Laffore in his biographical study of Julius Caesar Scaliger (Laffore 53-64). The tutor for the last year, Laurens de Lamarque, billed the father for several texts used by the boys. These included works by Aristotle, Ovid, Cicero, Horace, Virgil, Caesar, Justin, Valerius Maximus, and Textor. Lamarque also required his pupils to acquire a Greek grammar, Philip Melanchthon’s Greek grammar, a Portuguese dictionary, a New Testament, and the Psalms of David (Laffore 61).

After returning to Agen, Scaliger acted as his father’s amanuensis for the final three years of the latter’s life. This short apprenticeship allowed the young Scaliger to hone his skills as a scholar and classicist:

He, as long as I was with him (and indeed I was with him till his death), required from me daily a short declamation. I chose my own subject, seeking it in some narrative. This exercise, and the daily use of the pen, accustomed me to write in Latin. I was wont to take down my father’s verses at his dictation. From the task I imbibed some savor of the art of poetry. So both in verse and in prose composition my progress was, for my age, satisfactory, perhaps to others, certainly to my father. Sometimes he would lead me aside and ask me whence I drew those ideas and embellishments. I answered him truly, that they were mine, and original. (Robinson 30)

Under the tutelage of his accomplished father, Joseph acquired such a facility in writing Latin that at the age of sixteen he composed a tragedy on the myth of Oedipus. It has not survived, but his father admired it and Scaliger himself remained fond of it:

But he could not disguise from our friends his admiration for the first fruit of my intellect, the Tragedy of Oedipus. On this I had spent, so far as my youth permitted (for I was less than seventeen years old), all the ornaments of poetry and the resources of language. And indeed, unless memory deceives me, that product of my immaturity was such that even my old age need not rue it. (Robinson 30)

After the death of his father in 1558, Joseph moved to Paris, primarily to study Greek. His father had neglected to teach him that language, though the inclusion of an anonymous Greek grammar and Philip Melanchthon’s Institutiones Graecae Grammaticae among his required reading at Bordeaux suggests that he was not a complete novice in the language of Homer when he arrived in the Capital. The manner in which Scaliger taught himself ancient Greek has become legendary and speaks volumes of his work ethic and commitment to scholarship. In his own words:

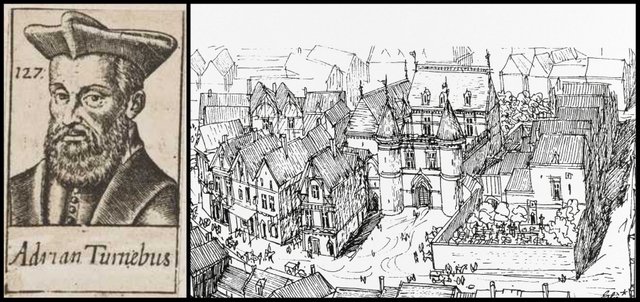

In my nineteenth year [1558-59], after my father’s death [21 October 1558], I betook myself to Paris from love of Greek, believing that they who know not Greek, know nothing. After attending the learned lectures of Adrian Turnebus for two months, I found I was throwing all my work away, because I had no foundation. I secluded myself, therefore, in my study, and, shut in that grinding-mill, sought to learn, self-taught, what I had not been able to acquire from others. Beginning with a mere smattering of the Greek conjugations, I procured Homer, with a translation, and learned him all in twenty-one days. I learned grammar exclusively from observation of the relation of Homer’s words to each other; indeed, I made my own grammar of the poetic dialect as I went along. I devoured all the other Greek poets within four months. I did not touch any of the orators or historians until I had mastered all the poets. (Robinson 30-31)

This phenomenal achievement is surely not to be taken literally—or is it? Some scholars have, indeed, taken Scaliger at his word, but Grafton is skeptical:

No doubt Scaliger did learn Latin and Greek on his own; no one has yet invented another way to do it. But his earliest book, a commentary on Varro’s On the Latin Language, showed that he had in fact taken in a great deal, by way of both fact and method, from those lectures of Turnebus that he remembered as merely baffling. Scaliger turned out to have learned his philologist’s craft not only from Turnebus but from Marc-Antoine Muret, Denys Lambin, and Jean Dorat—that brilliant team of classicists who dominated the Parisian Collège Royal, the ancestor of the modern Collège de France, in the mid-sixteenth century. They revolutionized the study of Greek drama and Roman elegy, and taught the Pléiade poets how to adapt classical prototypes in French. Scaliger learned their characteristic interests and applied their characteristic methods. He used their advice and their discoveries—though he did not always offer much credit for these. And he topped off the Parisian training that brought him into the most advanced literary circles of this time with two years of legal study at Valence under Jacques Cujas, the brilliant historian of Roman law whom he himself described as “the pearl of jurisconsults.” Yet none of this activity as pupil and disciple left enough of a precipitate in Scaliger’s mind to jog or catch his attention as he trawled backwards through his memories thirty years later. (Grafton 1988:582)

However he acquired the language, Scaliger made very good use of it over the next few years. His earliest extant writings are annotations he made around 1560-61 in an edition of Euripides. This copy of Hervagius’s Basel edition of 1544 is now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, as is a later edition of Euripides by Willem Canter (Antwerp 1571), which Scaliger annotated (Collard 242 ff). He also wrote a considerable quantity of Greek and Latin verse:

During those three years and after [1559-62], I amused myself by writing a good deal of Greek and Latin verse. I translated a quantity of Latin verse into Greek, aiming not merely to write Greek, but to write it as a native, For today many write Greek verses that are praised, but few write them with that felicity which one demands in the Greeks. We could have published our translations with a statement of the age at which each was written, as Politian did in his short Greek poems, which, for the most part, merited rather praise for youthful promise than publication by the mature Politian. But our unvarying dislike for self-advertisement restrained us from publishing our verses; though even now their issue would do us no dishonor. For I wrote them not to publish, but to indulge a lovely, mocking madness. I aver that it is not my fault, if some verses have appeared without my wish or command. (Robinson 31-32)

Politian (Angelo Poliziano) has been singled out by Anthony Grafton as perhaps the most important of Scaliger’s predecessors.

One of Scaliger’s earliest Greek poems was a translation of Catullus’s elegy, Coma Berenices [The Tresses of Berenice] (Catullus 66). The latter is believed to be a faithful Latin translation of Callimachus’s Βερενίκης Πλόκαμος, so Scaliger’s poem might be seen as an attempt to recover the lost original. It was included in The Collected Poems of Joseph Juste Scaliger, which Petrus Scriverius brought out posthumously in 1615. Other early poems have also survived, such as Catullus’s elegy to Hortalus (Catullus 65):

In September 1562 he dedicated the finished version, along with one of Catullus 65 to Muret then visiting Paris for the last time. (Grafton 1983:103-104)

Marc Antoine Muret was a notable Classical scholar of the day. He taught Latin at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux in 1547-48, a few years before Scaliger attended that school. Michel de Montaigne was among his pupils there.

Although Scaliger neglected to publish any of this verse, the fact that he dedicated some of his poems to fellow scholars proves that these early works were circulating in manuscript. His mastery of Greek, therefore, did not remain a secret and soon brought him to the attention of the best scholars in Paris:

No doubt Muret and Buchanan, both of whom had known his father in Bordeaux, helped him; but his own works were also an impressive visiting card. By 1563 we find him at the very centre of the Parisian scene, dedicating a Greek version of the Moretum to Ronsard. (Grafton 1983:104)

Like Muret, the Scottish humanist George Buchanan had taught Montaigne at the Collège de Guyenne before Scaliger attended the college. The poet Pierre de Ronsard was the leading member of the influential literary movement known as La Pléiade. The Moretum is an anonymous Latin poem, traditionally attributed to Virgil.

Not content to rest upon his laurels, Scaliger turned next to the study of Biblical Hebrew. His interest in the Semitic languages was first piqued by the French linguist and Kabbalist Guillaume Postel:

He began to study Hebrew, In response to the suggestion of Guillaume Postel, who interested him in Oriental languages in 1562. The two men were then sharing a bed in the house of a Parisian printer. They spent less than a week together, for Postel was arrested on suspicion of heresy and confined in a monastery, and Scaliger had to teach himself the language. He evidently used the Bible as he had used Homer for Greek, comparing the Hebrew text with the Vulgate; for a few years later he spoke biblical Hebrew to the Jews that he met In Italy and the south of France. (Grafton 1983:104)

Scaliger later claimed that his turn to Hebrew was self-motivated:

I had devoted two entire years to Greek literature, when an internal impulse [impetus animi] hurried me away to the study of Hebrew. Although I did not even know a single letter of the Hebrew alphabet, I availed myself of no teacher other than myself in the study of the language. (Robinson 31)

This is another example of Scaliger the emendator—of his own biography. As Grafton remarks:

Scaliger moves from possible suppressions of the truth to definite suggestions of the false. He says, first of all, that he decided on his own to turn to Oriental studies, thanks to an impetus animi. Yet in his other great self-presentation—his table talk, the Scaligerana ...—he tells a quite different tale. Staying at a bookseller’s house in Paris early in the 1560s, he shared a room and bed with the famous Cabalist Guillaume Postel. And Postel—so Scaliger later said—persuaded him that he should apply himself to Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac; that there were marvelous mysteries in these languages, and the Hebrews had fine authors, well worth reading, who had not yet been translated. This record comes from a lifelong, uncompromising friend of Scaliger. It was written down without publication in view, years before Scaliger described his youth and formation for the public. Hence it must take precedence over Scaliger’s later account. It has two crucial implications: that Scaliger suppressed a memorable fact about his youth, and that he did so in order to make his own account of that youth more consistent and impressive. (Grafton 1988:582-583)

It was around the same time that Scaliger converted to Calvinism, a decision which was to colour the remaining decades of his life, but one which he would not live to regret.

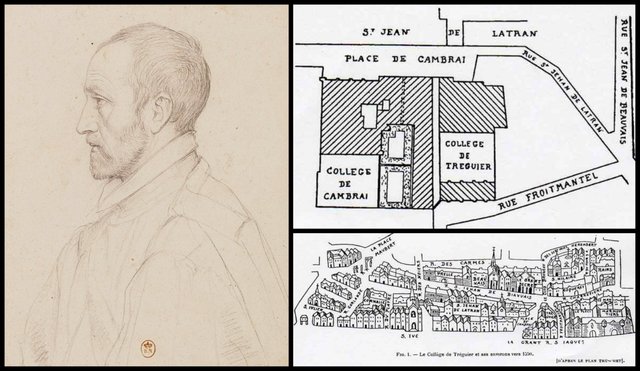

It was another member of La Pléiade, Jean Dorat, who probably had the greatest influence upon Scaliger’s education during these formative years in Paris. From 1556 to 1567, Dorat was Professor of Greek at the Collège Royal, which had its home at that time in the Collège de Tréguier and the Collège de Cambrai, close to the Sorbonne.

He became close to Dorat. His translation of the Orphica, which he achieved in five days in 1562, very likely reflects Dorat’s teaching. For Dorat regarded the poems as the works of the original Orpheus, and believed that they contained portentous secrets of ancient natural magic; and Scaliger, in his original subscription to the work, described Orpheus as ‛vates vetustissimus’ [the oldest prophet]. Certainly he heard Dorat discuss problems in Theocritus; whether he attended Dorat’s formal lectures we cannot say. In any event, he made a strong impression. (Grafton 1983:104-105)

Scaliger’s Orphica was first published posthumously in Opuscula Varia in 1610. It was also included in Petrus Scriverius’s edition of Scaliger’s Collected Poems of 1615.

It was also Dorat who first introduced Scaliger to the young French nobleman Louis Chasteigner de la Rochepozay. Chasteigner had been another of Dorat’s students in Paris. In 1563, Scaliger became Chasteigner’s literary companion. This appointment may be taken as marking the end of Scaliger’s formal education and the beginning of his career as a professional scholar. Within two years, he finally allowed one of his works to pass through the printing presses and to be launched upon the treacherous waters of public opinion. That work, the Coniectanea (Conjectures) on Marcus Terentius Varro’s De Lingua Latina (The Latin Language), would be dedicated to Chasteigner.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Christopher Collard, J J Scaliger’s Euripidean Marginalia, The Classical Quarterly, Volume 24, Number 2, Pages 242-249, The Classical Association, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1974)

- Euripides, Euripidu Tragodiai Oktokaideka, Johannes Hervagius, Second Edition, Basel (1544)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Anthony Grafton, Scholarship: Close Encounters of the Learned Kind: Joseph Scaliger’s Table Talk, The American Scholar, Volume 57, Number 4, Pages 581-588, Phi Beta Kappa Society, Washington, DC (1988)

- Vernon Hall, Jr, Life of Julius Caesar Scaliger, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 40, Number 2, Pages 85-170, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (1950)

- Daniel Heinsius (editor), Epistolae [All the Letters that Could Be Found of the Most Illustrious Man, Joseph Scaliger, Son of Julius Caesar Bordone, Collected and Edited for the First Time], Bonaventura & Abraham Elzevir, Leiden (1627)

- Daniel Heinsius, George Washington Robinson (translator), Funeral Oration on the Death of Joseph Scaliger, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1915)

- Marion Leathers Kuntz, The Original Language as Paradigm for the Restitutio Omnium, Allison P Coudart (editor), The Language of Adam: Die Sprache Adams, Wolfenbütteler Forschungen, Volume 84, Pages 124-125, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden (1999)

- Pierre Jules de Bourrousse de Laffore, Jules-César de Lescale (Scaliger), Recueil des travaux de la Société d’agriculture, sciences et arts d’Agen, Second Series, Volume 1, Part 1, Pages 24-69, Prosper Noubel, Agen (1861)

- Philippe Tamizey de Larroque (editor), Lettres Françaises Inédites de Joseph Scaliger, Alphonse Picard, Paris (1884)

- George W Robinson (translator & editor), Autobiography of Joseph Scaliger, with Autobiographical Selections from His Letters, His Testament, and the Funeral Orations by Daniel Heinsius and Dominicus Baudius, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1927)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Epistola de Vetustate et Splendore Gentis Scaligeræ et Iulii Cæsari Scaligeri Vita, Francis van Ravelinghen, Plantin Press, Leiden (1594)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, The Collected Poems of Joseph Juste Scaliger, Edited by Petrus Scriverius, Franciscus Raphelengius, Leiden (1615)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Jan Cornelis Woudanus (artist), Icones Leidensis, Number 31, Senate Chamber, Academy Building, Leiden University, Public Domain

- Bordeaux in 1550: Adolphe Héquet (artist), Patrice-John O’Reilly, Histoire Complète de Bordeaux, Part 1, Volume 4, First Edition, Pierre Chaumas, Bordeaux (1861), Public Domain

- Julius Caesar Scaliger: Johann Theodor de Bry (engraver), Jean-Jacques Boissard (artist), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Public Domain

- Adrianus Turnebus: Anonymous Engraving, Alfred Gudeman, Imagines Philologorum: 160 Bildnisse aus Zeit von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart, Page 7, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1911), Public Domain

- The Collège de Cambrai: Artist’s Impression of the Collège de Cambrai circa 1500, © Jean-Claude Golvin (artist), Fair Use

- Marc-Antoine Muret: Anonymous Engraving, Alfred Gudeman, Imagines Philologorum: 160 Bildnisse aus Zeit von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart, Page 8, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1911), Public Domain

- Denys Lambin: Anonymous Engraving, Alfred Gudeman, Imagines Philologorum: 160 Bildnisse aus Zeit von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart, Page 7, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1911), Public Domain

- Jacques Cujas: Anonymous, Public Domain

- Politian: Domenico Ghirlandaio (artist), Cappella Tornabuoni, Florence, Public Domain

- George Buchanan: Arnold Bronckorst (artist), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Pierre de Ronsard: Benjamin Foulon (artist), The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Public Domain

- Guillaume Postel: André Thevet, Les Vrais Pourtraits et Vies des Hommes Illustres, Volume 3, Folio 588, I Kervert & Guillaume Chaudière, Paris (1584), Public Domain

- Jean Dorat: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica Digital Library, Public Domain

- Ancient Street Plan of the Collège de Tréguier and the Collège de Cambrai: Adolphe Berty, Topographie Historique du Vieux Paris, Volume 6, Région centrale de l’Université, Plate 12, Between Pages 286-287, Imprimerie Nationale, Paris (1897), Public Domain

- The Collège de Tréguier and its Environs circa 1550: Olivier Truschet & Germain Hoyau, Plan de Paris, Basle (1552), Public Domain

- Louis Chasteigner: Jean Picart (engraver), Public Domain

- The Chasteigner Coat-of-Arms: Claude de Valles, Recueil de Tous les Chevaliers de l’Ordre du Saint Esprit, Paris (1631), Public Domain

Online Resources

- Autobiographical Extracts

- The Warburg Institute

- Leiden University Libraries

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger