If Joseph Juste Scaliger is to be believed, it was in 1567, when he was twenty-seven years old, that he compiled his notes on the so-called Appendix Vergiliana, a short collection of poems once thought to comprise the juvenilia of Virgil:

Scaligerana I, p. 21: ‛Confecit Conjectanea in Varronem anna aetatis vigesimo. Et lors, dit-il, étois-je lou comme un jeune lievre. Notas in lib. de Re Rustica anno 25. et in Catalecta Virgili anno 27.’

‛He completed his Conjectures on Varro at the age of twenty. “In those days,” he said, “I was as mad as a March hare. [He compiled] his notes on De Re Rustica at the age of 25, and those on the Vergilian Appendix at the age of 27. (Grafton 277, Desmaizeaux 21)

If this is true, Scaliger must have spent about five years on the work, which was first published in Lyon in 1572. This was six years after the appearance of his last work, the Alexander of Lycophron of Chalcis. Scaliger had spent most of 1565-1566 travelling with his patron Louis Chasteigner de la Roche-Posay, Seigneur d’Abain. Chasteigner had been appointed French envoy to Rome during the Armed Peace in the French Wars of Religion (1563-67):

As he and Chasteigner slowly crossed and re-crossed the Alps, they read Greek and Latin texts together. In Italy, where he travelled in both 1565 and 1566, he reached as far south as Naples; but most of his time was inevitably spent in Rome and in the cities of the North. (Grafton 119)

Among the authors they studied and discussed were Propertius, Statius and Polybius (Grafton 283-284). In Rome, Scaliger was introduced to other scholars and intellectuals by the French humanist [Marc Antoine Muret], (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muretus). Muret had taught Latin at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux a few years before Scaliger had attended that school, and had been a close associate of Scaliger’s father, Julius Caesar Scaliger. Scaliger, however, was more interested in the dead than in the living:

More interesting to Scaliger than Italian scholars were the material remains of the ancient world that he encountered everywhere in Italy. He marvelled at the size of Roman walls. He admired collections of ancient sculpture—though all he ever said about them was that the genitalia of the herms were very large. He copied down the texts of a great number of inscriptions from the collections of the Farnese and others, concentrating on those in Greek. In fact, he became so adept at deciphering the letters of worn inscriptions and emending and supplementing difficult texts that the results hidden in odd corners of his work sometimes surpassed those of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scholars. (Grafton 119)

In Rome and northern Italy—especially Mantua and Ferrara—Scaliger disputed with Hebrew scholars in Biblical Hebrew.

In 1566, after their return to France, Scaliger and Chasteigner embarked on a sort of Grand Tour of England and Scotland.

In Scotland, Scaliger noticed with interest the use of fossil coal and listened with pleasure to the lullabies sung by children’s nurses. Here too court life proved too wicked for his taste ... England was even less rewarding. He found the English barbarous and fanatical; their libraries held no interesting manuscripts, the fellows of their colleges lived a life of idleness, and they all had a pathological hatred for the French. Only Elizabeth impressed him, not by her beauty but by her fluency in several languages. (Grafton 120)

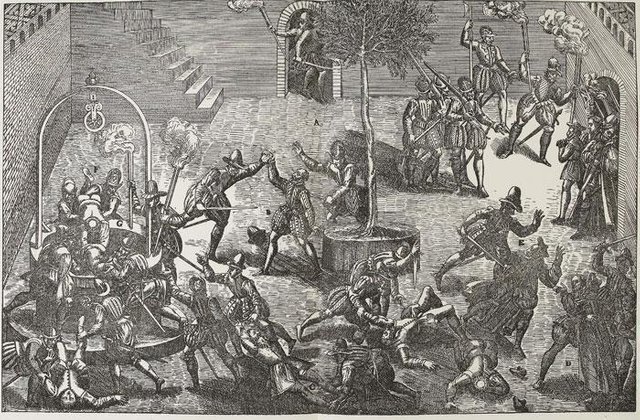

When the two companions returned to France in 1567, the Armed Peace had broken down and the Second War of Religion (1567-68) had broken out:

Returning to France, [Scaliger] found it in the throes of the Second Religious War. Fighting in the ranks of the Huguenots, he took an active part in this war and in the Third [1568-70] that soon arose out of it; during this time he lost what he still owned of his parents’ estate. Bitterly, he railed against the citizens of his native Agen. Most of his friends fell in the murderous battles. (Bernays 39-40)

These were years of camp life, dictated by the exigencies of the Second and Third Wars of the Huguenots (1568-70). Chasteigner was Catholic, but La Roche-Posay was regarded by the French government as a disaffected Huguenot village. Scaliger, it seems, spent some of these years in his native town of Agen, fighting on the side of his fellow Protestants (Pattison 228).

I have never understood exactly how Scaliger managed to juggle his service to Chasteigner, who was not only a Catholic but also a military commander in the field, and his loyalty to the Protestant cause. His biographers are never clear on the precise sequence of events, and Anthony Grafton’s recent work—Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship—seems to contradict the classic biography by Jacob Bernays (Berlin 1855). If Grafton is to be believed, when Scaliger and Chasteigner returned to France in 1567, they were able to remain out of the conflict for about a year. This allowed Scaliger time to study and begin working on his edition of the Virgilian Appendix:

By 1567 he was back in France. He made a beginning on a new project: an edition of and commentary on the Appendix Vergiliana, along with an assortment of Latin epigrams, some dealing with or attributed to Virgil and others anonymous but appealing for literary reasons. In preparation for this he collated or copied manuscripts from Pierre Pithou’s library, including a fourteenth-century manuscript of the Culex and the only manuscript of a fifth-century grammarian’s versified life of Virgil. For some unknown reasons, he had to leave Paris for the Limousin, but he sent the completed manuscript of his edition to Pithou, who was to oversee its publication.

At this point the civil war interfered decisively with Scaliger’s work. (Pithou was unable to find a publisher and had to return Scaliger’s manuscript. Scaliger was swept up in the horrors of the worst of the Religious Wars, the second and third of 1567 and 1568. What property his father had left him in Agen was stolen, and he was forced to become a soldier. There was no longer time for scholarship, and even his edition of the Appendix was lost. (Grafton 120-121)

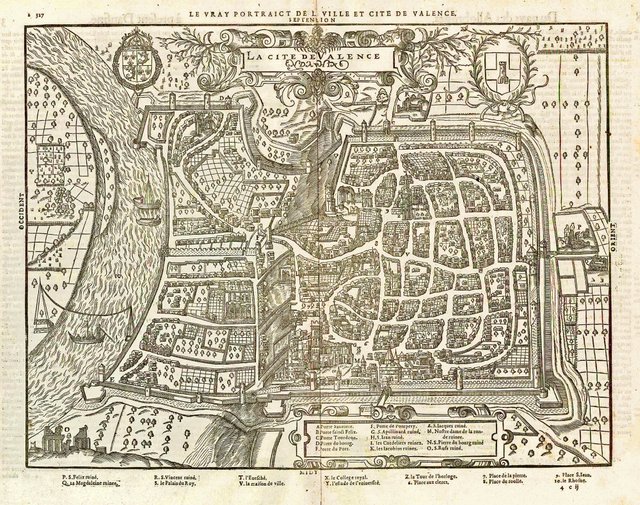

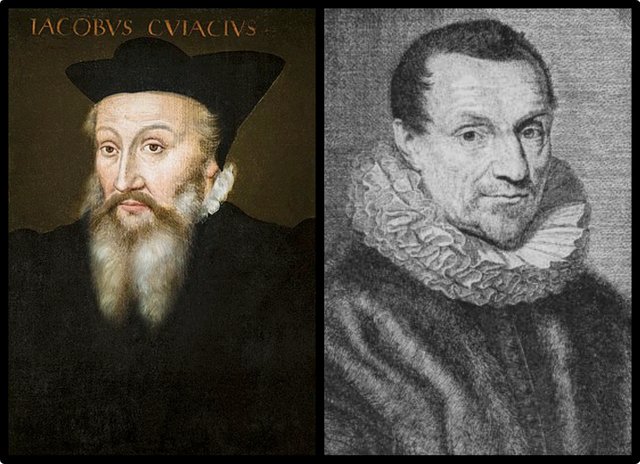

When the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (8 August 1570) brought the Third French War of Religion to a conclusion, Scaliger took up an offer to study Roman Law at the University of Valence under the foremost jurist of the day, Jacques Cujas. There followed more than two years of peaceful study in the Dauphiné, on the banks of the Rhône. Cujas quickly came to hold Scaliger in high esteem. In 1576, he even added one of Scaliger’s conjectural emendations to a revised edition of his Paratitla on Justinian’s Digest of Roman Law, adding the comment:

The most learned Joseph Scaliger emends it thus, with whom one disagrees at one’s peril. (Cujas 278)

(Note: Anthony Grafton ascribes this scholarly nod to Scaliger to the year 1570, when the first edition of Cujas’ Paratitla came out (Grafton 122), but it is missing from that edition.)

During these years, Scaliger made full use of Cujas’ extensive library, which filled seven or eight rooms and included five hundred manuscripts (Chisholm 614). The childless Cujas actually bequeathed this library to Scaliger, but by the time he died in 1590, his second wife had borne him a daughter, Suzanne, who inherited all his books (Pattison 151-152).

Scaliger also profited from Cujas’ extensive network of scholarly contacts. It was during his sojourn in the Dauphiné, for example, that Scaliger first made the acquaintance of the historian Jacques Auguste de Thou, who would remain a close friend for the remainder of his life.

Grafton sums up Scaliger’s time at Valence in the following manner:

His time with Cujas had exposed him to a great variety of studies, manuscripts, and men. But he had not had time at Valence to digest the new information and the new methods he encountered. Hence the one substantial piece of work that he produced there, his edition of the Appendix Vergiliana, ended as a fascinating but confused hodge-podge of clever but unconnected insights and remarkably elementary mistakes. (Grafton 124)

Nevertheless, the publication of Scaliger’s Appendix Vergiliana in 1572 was an event of note:

... the most significant event in the reception of the Appendix in the sixteenth century, and perhaps the biggest event in the reception history of the poem. (Burrow 5)

Appendix Vergiliana

As we have seen, Scaliger’s original manuscript of the Appendix Vergiliana was lost during the Second and Third Wars of Religion, but he somehow managed to recover it when he was at Valence.

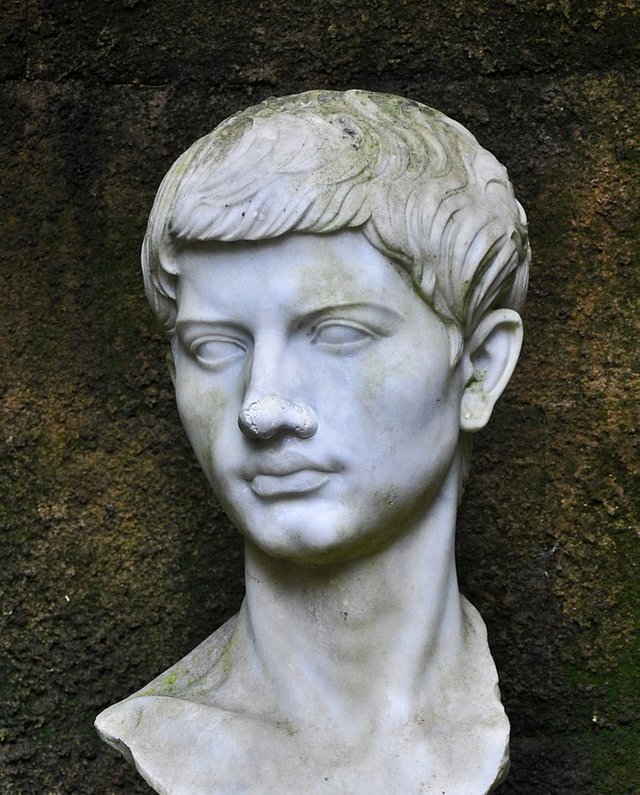

The Appendix Vergiliana is a collection of two dozen or so Latin poems from the 1st century CE. Scholars have not reached a consensus on the authorship of the various poems. The traditional view—that they constituted Virgil’s juvenilia—is no longer tenable, but the possibility remains that a few were indeed penned by Virgil. Some scholars, however, consider all of them spurious. Scaliger, himself, rejected some as spurious on the grounds of style.

It was Scaliger who first applied the term Appendix to the collection. Prior to that, the collection was generally published under the title Opuscula [Minor Works] as an appendix to the works of Virgil. Scaliger also established the ?? of the collection. Prior to 1572, editions varied in the number of works they included. It has been speculated that Scaliger’s use of the term Appendix

Scaliger’s tone in the volume is defensive, since he is anxious about the morality of the Priapea in particular; but he is also insistent that some of the poems in the Appendix are by Virgil, and that they are not just opuscula. It is not quite clear why Scaliger termed the collection an appendix, but it may have been to avoid that potentially pejorative term opusculum, and to make his collection appear newer in its content than it actually was. (Burrow 5)

Among the poems which Scaliger attributed to Virgil, he reserves his highest praise for the Ciris (The Sea-Bird):

It is, moreover, the most cultivated of poems, and is second to none in its Latinity, polish, or elegance; so much so that by its beauty alone it deserved to come down to us less corrupted. (Scaliger )

The Ciris was traditionally thought to have been written by Virgil when he was 15 or 16. Scaliger, however, thinks that the poem is much too sophisticated to be the work of a teenager, even if that teenager was Virgil:

Although we have not clearly ascertained in what year Virgil wrote this poem, nevertheless, it is quite clear that he wrote it at an older age than the author of his life will have us believe. The worthless grammarian Aelius Donatus] has him completing this poem when he was only fifteen years old. (Scaliger )

Scaliger emended Donatus’s XV [XVI in some manuscripts] to XXVI, making Virgil 26 when he penned the Ciris. Scaliger’s conjecture has been widely accepted, and modern editions of Donatus’s Vita Vergilii [Life of Virgil] now read XXVI.

The Culex and the Ciris emerge from Scaliger’s edition as not just opuscula or dubia [works of doubtful authorship]; they emerge as significant works of a poet on the threshold of maturity, albeit works which it is hard to pin down within an absolutely reliable chronology of Virgil’s verse. (Burrow 6)

Contents of the Appendix Vergiliana

The Culex is given the place of honour in Scaliger’s edition, followed immediately by the Ciris.

The Aetna Scaliger attributes to Cornelius Severus, an epic poet of the Augustan age. Severus is perhaps best known for a twenty-five line elegy on The Death of Cicero, possibly a fragment from his epic poem Res Romanae [Roman Affairs]. Scaliger appends this elegy to the Aetna, ascribing it to Severus’s De Bello Civili [The Civil War]. The Aetna is a 644-line poem on the origins of volcanism. It has also been attributed to Lucilius Junior, Procurator of Sicily during Nero’s reign, and Marcus Manilius, the author of the Astronomica and the subject of one of Scaliger’s future editions.

The Moretum [Pesto] is declared to be of uncertain authorship.

The Dirae [Curses] he attributes to Publius Cato Valerius, a minor poet of the 1st century BCE.

Of the three Priapea [Priapus Poems] he attributes the second to Albius Tibullus and the third to Catullus.

The next work is the Publii Virgilii Maronis Catalecta. This is the so-called Catalepton [Trifles], a collection of epigrams in various meters attributed to Virgil. Scaliger includes thirteen of the traditional fifteen or sixteen:

- 1 Plotius Tucca, a poet and friend. With Lucius Varius Rufus (see No 15 below), he prepared the Aeneid for publication after Virgil’s death.

- 2 Annius Cimber, a rhetorician.

- 6 Noctuinus, whose identity is still a mystery.

- 12 Noctuinus.

- 13 Lucius, also unknown.

- 14 Venus.

- 5 Syro, an Epicurean philosopher who numbered Virgil among his pupils.

- 10 Sabinus, a former mule-driver turned magistrate. This is a parody of Catullus 4, The Little Boat.

- 15 Lucius Varius Rufus, a friend.

- 8 Syro’s Villa. Syro’s school was in Naples, which is possibly the villa referred to.

- 9 Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, a general and patron of the arts.

- 3 Anonymous. This epigram is addressed to a successful general in the east, who fell from grace and was forced into exile. Alexander the Great, Phraates IV of Parthia, Pompey the Great, Mithridates the Great, and Mark Antony have been proposed as candidates.

- 4 Octavius Musa, a friend, and probably also a historian.

The next poem in the Appendix is Copa [The Female Tavern-Keeper], which is of uncertain authorship.

The Elegiae in Maecenatem (Two Elegies for Maecenas) Scaliger attributes to Albinovanus Pedo, a minor poet of the Augustan age. Maecenas died in 8 BCE, eleven years after Virgil, so these elegies cannot possibly by the latter.

These are followed by a third Elegy on the Death of Nero Claudius Drusus, which Scaliger also attributes to Pedo. Drusus was the father of the future Emperor Claudius, grandfather of Caligula, and great-grandfather of Nero. The elegy, addressed to his mother the Empress Livia, is now thought to be a 15th-century Italian imitation of the Augustan style.

To these Scaliger appends the only surviving fragment from Pedo’s poem about a voyage taken by Drusus’s son Germanicus down the River Ems and into the North Sea in 16 CE.

The next poem, Panegyricum ad Calpurnium Pisonem [In Praise of Calpurnius Piso], is attributed to Lucan, best known as the author of the epic poem De Bello Civili [The Civil War] (usually known in English as the Pharsalia). Lucan took part in Piso’s famous conspiracy against Nero, a decision which cost him his life. Today the work is usually called the Laus Pisonis (In Praise of Piso), and Lucan is considered a leading candidate for its authorship.

The next poem is De Mutatione Reipublicae Romanae [The Transformation of the Roman Republic], which Scaliger attributes to Petronius. A courtier during Nero’s reign, Petronius is generally accepted as the author of the satirical Roman novel the Satyricon. In fact, this poem comprises Chapters 119-124 of the novel, in which one of the characters, Eumolpus, illustrates the need for elevated content in poetry by composing a poem of almost 300 lines on the Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great (the same subject as the Pharsalia).

This brings to an end Scaliger’s edition of the Appendix Vergiliana.

Anthology

Not content to simply issue a new edition of the Appendix with a commentary, Scaliger added a supplement of early Latin poems that had never before been printed. This is still acknowledged to be the earliest anthology of Latin poetry.

Scaliger prefaces the anthology with the Life of Virgil by Focas (or Phocas), a Roman grammarian of the late 4th or early 5th century. His Vita Virgilii is written in dactylic hexameters, the epic meter form employed by Virgil in the Aeneid. Only the first 107 lines are extant. Joseph J Mooney’s translation is available online.

This is followed by a collection of pieces related to the works of Virgil—imitations of Virgil’s style, epitomes of the Aeneid, etc.

The anthology itself, which follows, takes up more than one hundred pages of the book and is divided into two books, each of which is further subdivided into categories—eighteen in Book 1 and fourteen in Book 2. The first of these is of human interest, while the second is devoted to the sciences: astronomy, geography, horology, etc. After the anthology, Scaliger lists the names of forty-three poets who contributed to it—not to mention the Innominati Poetae [Anonymous Poets], who comprise the majority of the contributors.

The contents of the anthology are as follows:

Focas Grammaticus, Life of Virgil: 142-145

Virgiliana: 146-188

Book 1: 189-241

Book 2: 241-260

Categories of Books 1 and 2: Pages 261-262

List of Authors: 263-264

Commentary

Following the anthology is Scaliger’s extensive commentary on the Appendix. This comprises almost three hundred pages of text and is followed by a short index. Scaliger does not comment on the anthology, and some contents of the Appendix are passed over without comment (eg De Mutatione Reipublicae Romanae):

Commentary: 265-548

Index: 549-566

Critique

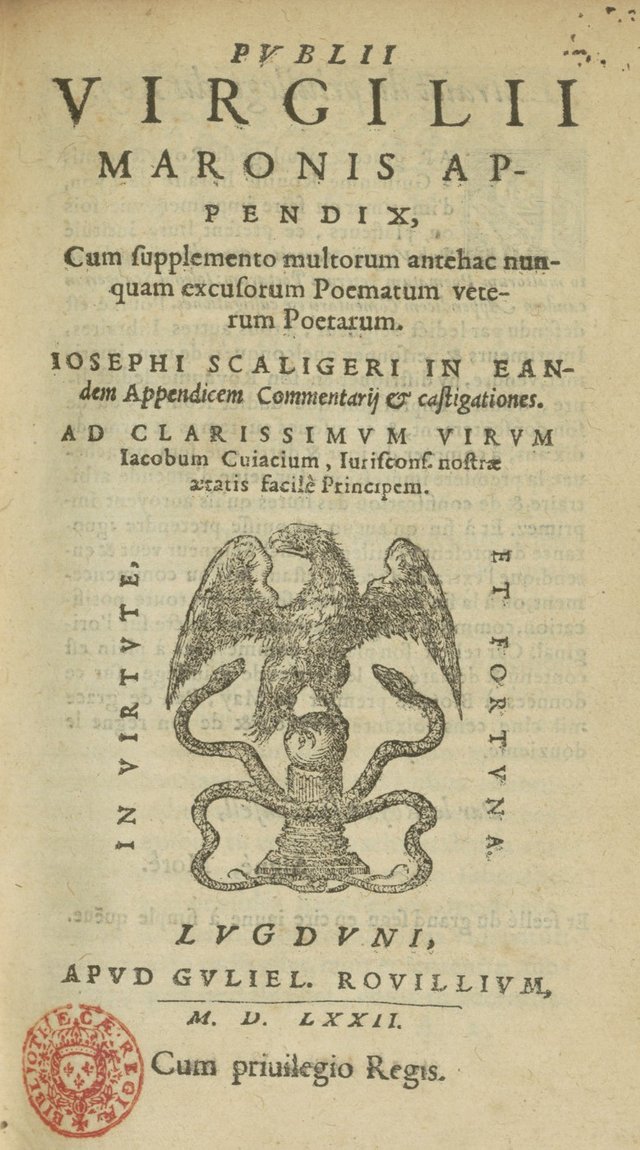

The full title of this edition is Appendix P. Virgilii Maronis cum Supplemento Multorum antehac Nunquam Excusorum Poematum Veterum Poetarum [The Appendix of Publius Virgilius Maro, with a Supplement of Many Never Before Printed Poems by Ancient Poets]. There is a wide consensus that the work lacks the scholarship and polish characteristic of Scaliger’s later editions:

The texts in his Appendix were, wherever possible, a simple reprint of the existing vulgate: in most cases, the edition of the Appendix that Theodore Poelman had published at Antwerp in 1566. Scaliger made no attempt to emend this text even where he was convinced that his manuscripts afforded better readings. Even when he was sure that lines in the vulgate text had been transposed, he did not transpose them in his edition, but simply recorded his belief in the commentary. As to the texts that he published for the first time, here too his procedures were careless. He rarely gave any indication of the manuscript sources on which he had drawn, nor did he make any attempt to distinguish between manuscript readings and his own conjectures. (Grafton 124)

As we have seen, Scaliger began his edition of the Appendix in 1567, about three years before he began to study with Cujas, and tried unsuccessfully to have the work published in the same year. His original manuscript went missing during the Second and Third Wars of Religion (1567-70), but somehow Scaliger recovered it and resumed work on it in the Dauphiné. It is possible, however, that he never bothered to revise the work he had already completed in the light of what he was learning from Cujas. Instead, he simply compiled the poems that make up the anthology and added them as a supplement to the Appendix. It is surely significant that his commentary only discusses the poems in the Appendix proper. If this an accurate account of the course of events, then it is not at all surprising that the work conforms to the principles of scholarship Scaliger learned in Paris in 1558-63:

This careless and slapdash method of working, designed to produce a readable text rather than a historically justifiable one, recalls the methods of Scaliger’s Parisian teachers rather than the professionalism of Cujas. So do the contents of his commentary. Scaliger ventures dozens of conjectures, sometimes three or four for the same word. He heaps up Greek parallels. He takes pains to point out that the critic must be above all an expert on style, and that such knowledge can only be acquired by those aristocrats among critics who can write Latin and Greek as natives. Only absolute control of poetic style could enable the critic to determine the authorship of the various poems that make up the Appendix. (Grafton 125)

Grafton compares the Appendix to Scaliger’s first publication, the Coniectanea (Conjectures on Varro) of 1565 (Grafton 125).

In 1595, one of Scaliger’s pupils at Leiden, Friedrich Lindenbrog brought out a revised edition of the Appendix. Lindenbrog added about forty-eight pages of his own notes on both the Appendix and the anthology. Scaliger, it seems, did not take this opportunity to alter the work he had done more than twenty years before.

The End of the Affair

As Scaliger was putting the final touches to his edition of the Appendix Vergiliana, political events overtook him, bringing his pleasant sojourn in the Dauphiné to an end:

In 1572 the idyll ended. Jean Monluc, the irenic Bishop of Valence, was sent by Catherine de’ Medici to try to win the throne of Poland for her son, the Duke of Anjou. Monluc was known to like Protestants; Cujas persuaded Scaliger that it would be worth his while to go. Cujas and Scaliger travelled to Lyons, where Scaliger hastily finished reworking his edition of the Appendix Vergiliana, the manuscript of which he had recovered and enlarged. On 22 August 1572 Scaliger finished his revisions, scribbled two dedicatory prefaces, and gave the work to his printer. Then he left for Strasbourg, where he was to meet Monluc. (Grafton 123-124)

Less than two days later, in the early hours of 24 August, France was thrown into chaos by the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Scaliger would never see Valence again.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Colin Burrow, English Renaissance Readers and the Appendix Vergiliana, Proceedings of the Virgil Society, Volume 26, Pages 1-16, London (2008)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), The Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 7, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- Jacques Cujas, Paratitla in Libros Quinquaginta Digestorum seu Pandectarum Imperatoris Iustiniani [Summary in Fifty Books of the Emperor Justinian’s Digest or Pandects], Guillaume Rouillé, Lyon (1580)

- Pierre Desmaizeaux (editor), Scaligerana, Thuana, Perroniana, Pithoeana, et Columesiana, Volume 2, Prima Scaligerana, Seconda Scaligerana, Covens & Mortier, Amsterdam (1740)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Joseph J Mooney, The Minor Poems of Vergil ... Metrically Translated into English, Cornish brothers Limited, Birmingham (1916)

- Mark Pattison, Joseph Scaliger, in Essays, Volume 1, Pages 132-243, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1889)

- Theodor Poelman, Pub. Virgilii Maronis Opera, Christopher Plantin, Antwerp (1566)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Appendix Vergiliana et Catalecta [Virgilian Appendix and Anthology of Latin Poetry], Guillaume Rouillé, Lyon (1572)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Friedrich Lindenbrog, Appendix Vergiliana et Catalecta, Revised Edition, Franciscus Raphelengius, Leiden (1595)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Nicolas Eustache Maurin (painter), François-Séraphin Delpech (engraver), Bibliothèque de Genève, Public Domain

- Louis Chasteigner: Jean Picart (engraver), The British Museum, 1910,0610.39 London, Public Domain

- Chasteigner Coat of Arms: De Valles, Recueil de tous les chevaliers de l’ordre du Saint Esprit ... avec les armoiries, etc, Paris (1631), Folio 96r, Public Domain

- Queen Elizabeth I: The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, Anonymous Painter, National Portrait Gallery London, Public Domain

- La Michelade: The Massacre at Nîmes (1567): Frans Hogenberg (engraver), Geneva, Public Domain

- Map of Valence, François de Belleforest, La Cosmographie Universelle de Tout le Monde, Volume 1, Page 327, Nicolas Chesneau, Paris (1575), Public Domain

- Jacques Cujas: Anonymous Portrait, Cour d’Appel de Toulouse, Toulouse (1580), Public Domain

- Jacques Auguste de Thou: Jean Morin (engraver), Louis Ferdinand Elle (artist), Public Domain

- Title Page of Scaliger’s Appendix Vergiliana (1572): Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Public Domain

- Bust of Virgil: Anonymous Sculptor, Parco della Grotta di Posillipo, Naples, Italy (1st Century), Public Domain

- Mount Etna and Catania: © BenAveling (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Virgil’s Tomb, Naples: ©Mentnafunangann (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Salvo Randone as Eumolpus in Fellini’s Satyricon (1969): Satyricon (1969), Federico Fellini (director), Giuseppe Rotunno (cinematographer) Fair Use

- Pietole Vecchia (Andes), Birthplace of Virgil: © Google, Fair Use

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (Calbet): Antoine Calbet (artist), La Salle des Illustres de l’Hôtel de Ville d’Agen, Agen, Public Domain

- Anthony Grafton: © The Trustees of Princeton University, Fair Use

- Friedrich Lindenbrog: David Kindt (artist), Hamburg State and University Library, Hamburg, Public Domain

Online Resources

- The Warburg Institute

- Leiden University Libraries

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Jacob Bernays: Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Autobiographical Extracts