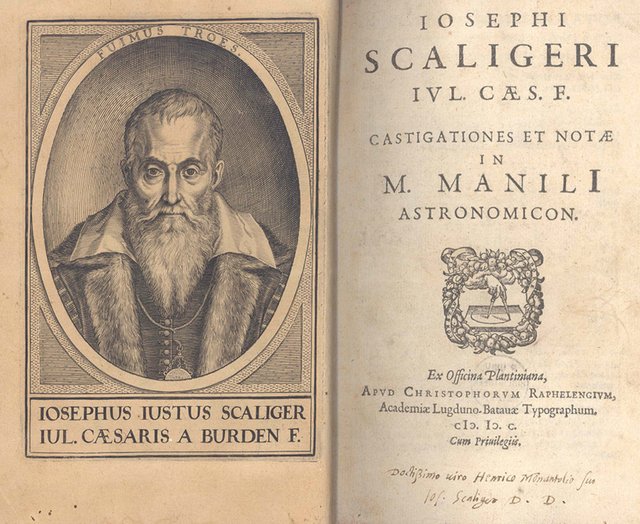

Joseph Juste Scaliger was a scholar of many talents and interests. As a polyglot and a philologist he was always curious about the evolution of languages and their relationships to one another. The publication of the second edition of his opus magnum De emendatione temporum in 1598 ensured that his fascination with ancient calendars and the marking of time remained undimmed. And work on his second edition of the Astronomica of Marcus Manilius―published in Leiden in 1599―reignited his interest in celestial phenomena.

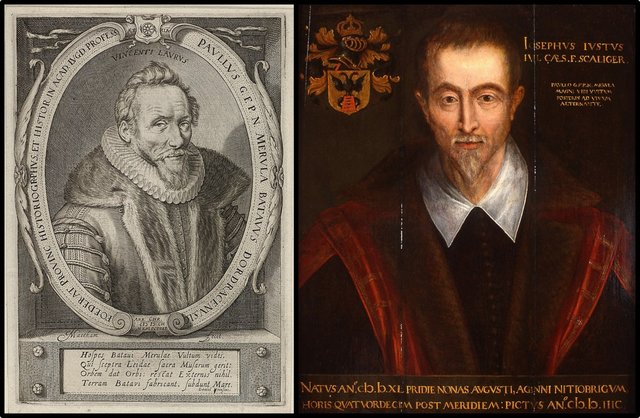

Around the same time he wrote a short Diatribe on European Languages for his friend Paulus Merula, librarian of the Leiden University Library, who was writing a Cosmographia generalis―a general description of the Universe. In this brief treatise―it is barely three pages long―Scaliger applies the comparative method to the word for God in various European languages. Foreshadowing the far-reaching achievements of later linguists, he is led to sketch a family tree of these languages, postulating the existence of four main language families (Italic, Hellenic, Germanic, and Slavic, in modern terminology) and seven minor ones (Albanian, Tatar, Hungarian, Finnish, Irish, Welsh, and Basque).

These disparate interests, however, were about to be channelled into another major project:

By 1599 Scaliger finally found a new and larger focus for these scattered themes and interests. He began to establish a critical text of the most substantial ancient chronological text, Jerome’s adaptation of the Chronicle of Eusebius―a compendium vast enough to give him ample scope for reflection on history, language, chronology, and much else. All the themes we have traced in his correspondence and table-talk would surface again in the course of his work on this text. ―Grafton 501

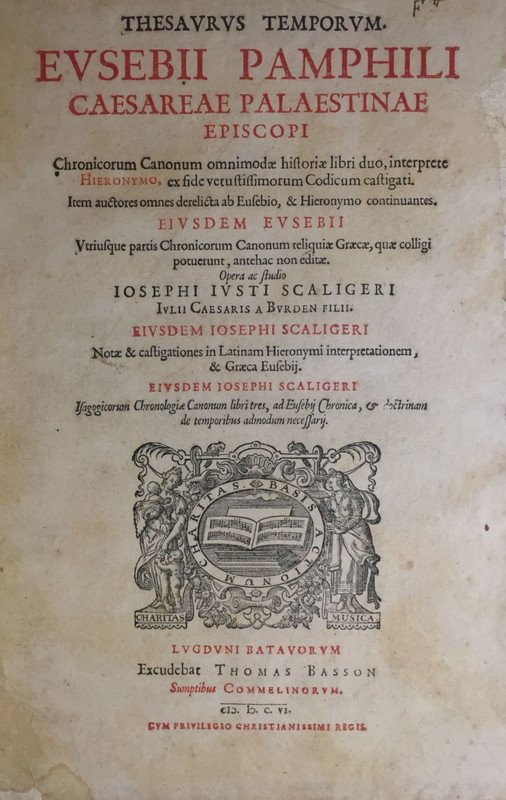

Eusebius and the Thesaurus Temporum

Scaliger would toil on this titanic project for more than half a dozen years:

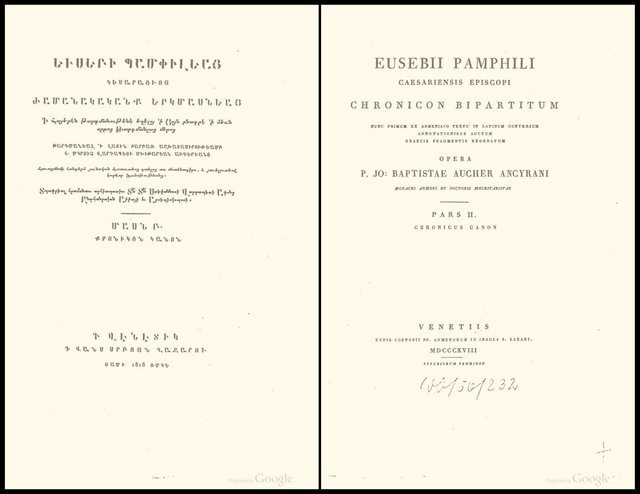

Meantime the synoptic presentation of world-history which he had proposed was slowly taking shape. Seeking for some central point about which he might group the far-flung researches of his De Emendatione Temporum, he selected the so-called Chronicle of an ancient worker in the same field as himself, Eusebius, the fourth-century Bishop of Caesarea. The original Greek Chronicle of Eusebius had completely disappeared except for a few recognizable quotations in Byzantine authors, and a highly abridged Latin rendering by St. Jerome. Scaliger now set himself the incredible task of recovering from every conceivable ancient source the lost material of the original chronicle, and of restoring it completely in the Greek form of the original. From his study of the Byzantine fragments he conceived the boldly original idea that Eusebius’ work had consisted of two books, and that St. Jerome had abridged and translated only the second, which, being in the form of chronological tables, was the more practically useful of the two. The first book Scaliger decided had contained documentary epitomes of the Greek writers on Oriental history and it was this which he particularly determined to recover. Yet despite his microscopic examination of all ancient literature for evidences of Eusebian fragments, his collection was meagre and his task seemed doomed to failure. Then, with the extraordinary good fortune which so often smiles upon bold endeavor, he came in 1601 upon the track of a hitherto unknown Byzantine chronicler of the ninth century, the monk George, syncellus, or patriarch’s coadjutor, at Constantinople. To Scaliger’s unbounded delight this work, now well known as the Chronicle of Syncellus, proved to contain far more of the original Eusebius than all the previous fragments which he had collected with so much labor. Thus in the year 1606 he published his restored Greek Eusebius as the central point of his two huge folio volumes of the Thesaurus Temporum—or “Treasure-House of Dates”—in which every extant relic of Oriental, Greek, and Roman chronology is arranged in due order and restored to intelligibility. This is the work in which, as Professor Garrod of Oxford remarked only a few years ago, “one half of modern scholarship has its forgotten source.” ―Blake 89–90

Scaliger was slow to arrive at this realization that Eusebius’s Chronicon had comprised two books, only one of which Jerome had translated in abridgment. Initially he had only set out to produce a critical edition of Jerome’s Latin text. By the end of 1600 he was already boasting that he had restored Eusebius to life. But he had spoken too soon, and the difficulties presented by hopelessly corrupt manuscripts altered his plans significantly:

The text proved terribly corrupt, and ... Further enquiries ... at first turned up only other manuscripts that shared the defects of the first one. When better ones appeared, Scaliger had to rework his text from the beginning. At the same time, he found himself embarked on a parallel task far more ambitious and delicate than any normal edition. Casaubon suggested in December 1599 that it would have been wonderful if Scaliger ‛had managed to obtain a Greek text of Eusebius’ Chronicle’, though only the Latin had been sighted in modern times. ―Grafton 502

Scaliger first came across the work of the 11th-century Byzantine scholar Cedrenus, which drew indirectly on Eusebius’s original Greek text. But Scaliger realized that he would require access to George Syncellus’s Chronicle if he wished to do justice to Eusebius. Failing to lay his hands on a good manuscript of Syncellus―he had his eye on an 11th-century manuscript Casaubon had discovered in Paris―he was forced to suspend work on the Thesaurus Temporum from the late summer of 1601 until June 1602.

Corpus inscriptionum

Scaliger was not the sort of man to sit on his hands. He devoted the intervening months to a new project. In 1588 his predecessor at Leiden Justus Lipsius had published an edition of the ancient inscriptions collected by the Flemish theologian Martinus Smetius, to which he had added his own collection, the Auctuarium:

- Justus Lipsius, Martinus Smetius, Inscriptionum Antiquarum, Auctarium, Franciscus Raphelengius, Leiden (1588)

... Scaliger studied it extensively. He noted that he and others had collected a great many inscriptions that it lacked. By 1598 he had entrusted these to [the printer Jean] Commelin in Heidelberg, for inclusion in a new Corpus inscriptionum. In July he asked Janus Gruter, who lived and worked in Heidelberg, to serve as editor, and insisted that he himself need not even be mentioned in the finished work ... ―Grafton 503

Gruter, however, was the sort of man to sit on his hands, so Scaliger ended up doing more of the work himself than he had planned. He was particularly aggrieved to have to slave away at the book’s twenty-four detailed indexes. The result was a tome of encyclopaedic scope:

The finished book filled more than 1,100 large folio pages ... [Gruter’s] dry and straightforward Corpus, with its detailed prefatory specification of its sources, remained the standard one for two hundred and fifty years. It was largely the result of Scaliger’s energy and learning, and even more of his prescient belief that inscriptions were particularly revealing, that they could make the texture of ordinary life in the ancient world more concrete and vivid than any other source. ―Grafton 503 ... 504

Scaliger’s indexes alone took up more than 200 of the book’s 1100 folio pages. Scaliger was proud of them and even urged Gruter to draft a commentary on them rather than on the texts:

Modern epigraphers and historians have taken Scaliger exactly at his word. They have described him as the inventor of the systematic subject-index to inscriptions, one of the most powerful tools for information-retrieval that classical scholars had until the twentieth century, and have shown that his work still provided the model for the indexes that finally supplanted Scaliger’s, those of the Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum that followed his example on the still grander scale made possible by public funding and formal collaboration. ―Grafton 505

But, as usual, Scaliger had failed to acknowledge his indebtedness to one of his predecessors:

Smetius too had seen that a systematic index could make a good corpus of inscriptions into a great source of information. He duly composed one and inserted it into the final draft of his compilation ... and Lipsius had it printed along with the corpus itself in 1588. The indexes as well as the texts immediately caught Scaliger’s eye ... On the face of it, then, one might wonder if Scaliger really drew up his own indexes de novo. ―Grafton 505

As Grafton goes on to demonstrate, Scaliger clearly had Smetius’s indexes at his elbow when he was drafting his own. His first draft was even accomplished by a sort of copy-and-paste technique, though when he came to revise the work, he went well beyond what Smetius had done (Grafton 505).

George Syncellus

In June 1602 Scaliger finally got his hands on the Paris manuscript of George Syncellus’s Ἐκλογὴ Χρονογραφίας, or Extract of Chronography:

- Codex Parisinus Bibl. Nat. Graecus 1711, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

This 11th-century manuscript contained a complete text of Syncellus’s chronicle. It had been discovered by Isaac Casaubon, who arranged for its loan to Scaliger:

The history of the MS ... is curious. It was preserved in the library of the patriarch at Constantinople. It reappeared in the Royal Library of France [the Bibliothèque du roi, which was then located at the Collège de Clermont in Paris]. A notice, in Greek, appended to the MS states that it was purchased at Corinth, for four pieces of gold (χρυσινοῦς), by John Abrami (or Abrams), in the month of November, 1507 ... It was probably one of the many waifs from the Ottoman capture of Constantinople. For some time it was believed to have been lost from the Royal Library. It reached Scaliger’s hands. It was, in time, restored to the royal repository, where it still remains, if it did not perish in the fires of the Commune. ―McClintock & Strong 85

Unlike the Tuileries Palace, the manuscript did survive the Paris Commune of 1871 and is still held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the successor of the Royal Library, at its Richelieu Site:

The Chronicle of Georgius Syncellus (ca 800), covering the period from Creation to the first year of the emperor Diocletian [284 CE], is unique among such works of Byzantine chronography for its detailed treatment of antiquity, with frequent and often lengthy citation of sources. Syncellus is consequently our best and sometimes our only source for significant fragments of a number of ancient works otherwise wholly or partially lost. Of the many manuscripts that attest to the work of Syncellus, most contain only the latter third of the chronicle, from the time of Julius Caesar, followed by the continuation written by Theophanes. This portion of Syncellus derives chiefly from Josephus and the Historia Ecclesiastica of Eusebius, and is of less interest and importance than the pre-Roman sections. The only complete manuscript of the entire work hitherto known is the famous Paris manuscript (Bibliotheque Nationale gr. 1711) written in the year 1021 and discovered by Isaac Casaubon about 1600. From this manuscript Joseph Scaliger in 1606 published much of the material that he believed Syncellus had derived from the then lost first book of the chronicle of Eusebius. ―Mosshammer 289

Syncellus opened Scaliger’s eyes to the disparity between Jerome’s Latin epitome and the original Greek Chronicon of Eusebius. And while Scaliger was contemplating the vast amount of work required to do justice to Eusebius, he had not lost sight of his earlier masterpiece De emendatione temporum, which also required his attention:

... Scaliger found that his editorial task bulked even larger than he had realized. The Latin text of the Chronicle was only a corrupt fragment of the Greek original, and that in turn posed difficult problems of analysis and reconstruction. Yet Scaliger set to work ... He drew up a vast commentary on his texts. And he decided that he had to undertake anotter, complementary task. He saw that even the second edition of De emendatione had not met the needs of the readers he respected most. It was just too hard ... Scaliger began to compose another systematic work on calendars and epochs to accompany his texts and notes. ―Grafton 506–507

This new work was the Isagogicorum chronologiæ canonum libri tres [Three Books of Introductory Rules of Chronology], a systematic introduction to De emendatione temporum. It would be published between the same covers as the Thesaurus temporum in 1606, taking up the last 382 pages of the volume’s 1460 pages.

But by now texts and treatises had multiplied far beyond the original plan. Even Scaliger confessed in September 1603 that he had written a ‛longum & operosum volumen’ [a lengthy & laborious volume]. It was no longer an edition [of Jerome or Eusebius] but a vast compendium―a Thesaurus temporum [A Treasure House of Dates] ―Grafton 507

As Scaliger laboured on this mighty tome, he did not labour in isolation. These years were marked by the usual controversies and polemics that dogged Scaliger’s career, as we shall see in the next article.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Warren Blake, Joseph Justus Scaliger, The Classical Journal, Volume 36, Number 2, Pages 83-91, The Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Inc, Chicago (1940)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Justus Lipsius, Martinus Smetius, Inscriptionum Antiquarum, Auctarium, Franciscus Raphelengius, Leiden (1588)

- John McClintock & James Strong, Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Knowledge, Volume 10, Harper and Brothers, New York (1881)

- Alden A Mosshammer, The Barberini Manuscript of Georgius Syncellus (Vat. Barb. Gr. 227), Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, Volume 21, Number 3, Pages 289–295, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina (1980)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum, Johannes Janssonius, Amsterdam (1658)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Diatribe on European Languages, Opuscula Varia, Pages 119–122, Adrien Beys, Paris (1610)

Image Credits

- Second Edition of Scaliger’s Manilius: Joseph Juste Scaliger, Castigationes et notae in M Manili Astronomicon, Christoph Raphelengius, Leiden (1600), Anonymous Engraving, Public Domain

- Paulus Merula: Jacob Matham (engraver), Daniel Heinsius (text), Collection of Carl Gottfried Voorhelm Schneevoogt, Haarlem (1602), Public Domain

- Portrait of Scaliger: Paulus Merula (artist), Icones Leidenses, Number 28, Leiden (1597), Public Domain

- Armenian Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicon (1818): Giovanni Battista Auchèr (translator & editor), Eusebii Pamphili Chronicon Bipartitum Graeco-Armeno-Latinum, Part 2, Auchèr, Venice (1818), Public Domain

- Jan Gruter: Johann Jacob Haid (engraver), Alfred Gudeman, Imagines Philologorum, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1911) Public Domain

- Justus Lipsius: Peter Paul Rubens (artist), After Abraham Janssens I (artist), Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, Public Domain

- Eusebius of Caesarea: Charles Joseph Hullmandel (lithographer), Public Domain

- Bibliothèque nationale de France: Département des manuscrits (Reading Room): © Jean-Christophe Ballot (photographer), OPPIC/BnF, Fair Use

- Thesaurus Temporum (1606): Joseph Justus Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum (1606), Titlepage of a First Edition, Leiden, Public Domain