Did you know that there are far fewer women than men working in scientific, mathematical, engineering and technological (STEM) careers in the UK? Just 13% of workers in these industries are women, according to Women Into Science and Engineering (WISE), one of the groups that had been set up to attempt to tackle this issue.

The STEM fields have always had a woman problem. A 2011 report by the US Department of Commerce found that only one in seven engineers is female. Less than 20% of bachelor’s degrees in computer science go to women, even though female graduates hold 60% of all bachelor’s degrees. There aren't a lot of women in engineering either. Women have received 45% of all math- and science-related doctoral degrees in 2012; only 22% were in engineering. Additionally, women have seen no employment growth in STEM jobs since 2000.

So who is to blame for these crazy facts and dearth of female scientists – a lack of female role models, gender stereotyping, and less family-friendly flexibility in the STEM fields.

And what difference does it make when there is a lack of women in science? Well, A LOT.

According to National Geographic, countless women with heart disease have been misdiagnosed in emergency rooms and sent home because they exhibited different symptoms from men. Women also have suffered disproportionately more side effects from various medications because the recommended doses were based on clinical trials that focused on men.

The model used in biomedical research to design drugs and products has been predicated on the physiology of an average-size male. Even the animals used in scientific experiments have been male because researchers have been concerned that hormone fluctuations in female animals would tilt the results of tests.

“Sex, the biggest variable, as a result has not been systematically evaluated and reported in the same way as variables like time, temperature, and dose, even in diseases that are female dominated,” says Teresa K. Woodruff, director of the Women's Health Research Institute at North-western University.

The National Institute of Health, the primary US agency responsible for health-related research, is now correcting this procedural bias. It announced in May 2014 that the researchers it funds would be required to start testing theories in female lab animals and female tissues and cells, and to consider sex as a variable in experiment design and analysis.

The new NIH stance is what Londa Schiebinger, a leader in the Gendered Innovations movement (an international collaborative made up of natural scientists, engineers, and gender experts), calls a gendered innovation which will make science more relevant to women. “We can be interested in women and science, and their participation, and how many are here and there. But the big difference is, what knowledge and technologies do you have? What's the outcome? Who are things designed for?” she says.

Schiebinger strongly believes that taking gender into account in research can make a difference in areas such as stem cell work, technologies to assist the elderly, and better diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in men. “Involving more qualified women, as well as gay people, African Americans and Latinos, those with physical disabilities can enrich the creativity and insight of research projects and increase the chances for true innovation,” says Scott Page, a professor at the University of Michigan.

This problem affects everyone—children, women, and men. What science decides to solve and for whom things are designed have a lot to do with who's doing the scientific inquiry. Analysts say that more women are needed in research to increase the range of inventions and breakthroughs that come from looking at problems differently from how men typically do.

Gross, a Stanford psychologist, thinks women tend to exhibit more communal qualities (fostering good relations to build community, creating an inclusive environment), while men tend to exhibit more agency qualities (taking leadership, making things happen). Having women's emotional skills in the mix, he says, can yield immensely positive results in scientific research.

Women are well-represented in biological sciences, psychology, and medicine; however, not proportionally represented among its leaders. Science professors at American universities widely regard female undergraduates as less competent than male students with the same accomplishments and skills, a 2012 study by researchers at Yale concluded. The report found that professors were less likely to offer the women mentoring or a job. And even if they were willing to offer a job, the salary was lower.

“We don't want to just have more talented women We want to make sure that women with well-developed skills don't end up—and it happens all the time—stuck at lower levels working in labs. You need them at leadership positions directing the field,” Gross adds.

But then there is hope.

In 2013, Disney announced Marvel’s Thor: The Dark World Ultimate Mentor Adventure, a nationwide STEM contest, in conjunction with the November 8 release of the film, to empower girls 14 years and up. Girls in grades 9 through 12 had embarked on a journey to discover their potential and future in the world of STEM. The contest encouraged girls to reach out to STEM mentors in their area and interview them to understand who they are, and why learning from these mentors can impact their futures. The 10 winners went to Hollywood for a week to meet some of the most incredible women in science.

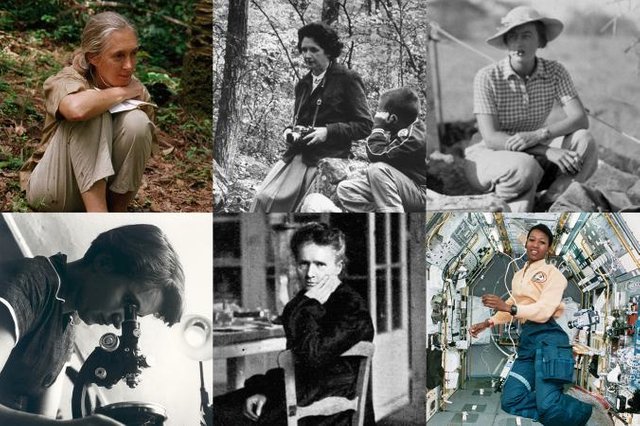

Although gender equality can’t be achieved overnight, what we can do is dedicate ourselves to changing the norms and stereotypes that inhibit women from tapping into their true potential. Female participation must be encouraged in the STEM fields from a young age. There is evidence that gender bias has affected research outcomes and damaged women's health, so hopefully the new approach to make science more relevant to women will bring to the world more female role-models like Jane Goodall, Rachel Carson, Mary Leakey, Mae Jemison, Marie Curie, and Rosalind Franklin.

You want to support Anonymous Independent & Investigative News? Please, follow us on Twitter: Follow @AnonymousNewsHQ

This is mostly based on Marxist sociological nonsense. There are less women in the sciences because less women prefer to become scientists. There is nothing stopping them. To say otherwise is not only factually inaccurate, but it screams of an ideological perspective which has repeatedly been debunked such as the gender wage gap....just wow.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit