The total amount of water in the world is almost constant. It is estimated to be 370,000 quadrillion gallons, 97% of which is the water in the oceans, which is salty and unfit for human consumption without an expensive treatment. The remaining 3% is known as fresh water, but 2% of that is the glacier ice trapped at the North and South Poles. Only 1% is available for drinking water.

Pure water is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless liquid. The depth and light give it a blue or bluish-green tint. Tastes and odors in water are due to dissolved gases, such as sulfur dioxide and chlorine, and minerals. Water exists in nature simultaneously as a solid (ice), liquid (water) and a gas (vapor). Its density is 1 g/mL or cubic centimeter. It freezes at 0°C and boils at 100°C. When frozen, water expands by one ninth of its original volume.

Water Supplies

There are two main water supplies: surface water and groundwater.

Surface Water Supply

Surface water supply is the water from the lakes, reservoirs, rivers and streams. These water bodies are formed of water from direct rain, runoffs, and springs. A runoff is the part of rain water that does not infiltrate the ground or evaporate. It flows by gravity into the water body from the surrounding land. This drainage area is known as the watershed. One inch of runoff rain/acre is equal to 27,000 gallons (1 hectare = 2.47 acres) or 1 inch of runoff rain/ha is equal to 67,000 gallons. Watershed characteristics affect the water quality, therefore protection of these watersheds is very important.

Surface waters can be classified into lentic (calm waters) and lotic (the running waters).

Lentic Water Supplies

Lentic waters are the natural lakes and impoundments or reservoirs. Natural lakes of good quality water are very good sources of water. Impoundments are useful, as they eliminate seasonal flow fluctuations and store water for adequate water supply, even under high consumer demand periods, such as drought in summer. Impounding also helps in the pretreatment of water by reducing turbidity by sedimentation and reducing coliform bacteria and waterborne pathogens through exposure to sunlight. Algal growth and other planktons, drifters formed of free-floating algae, protozoans and rotifers, can cause taste and odor problems.

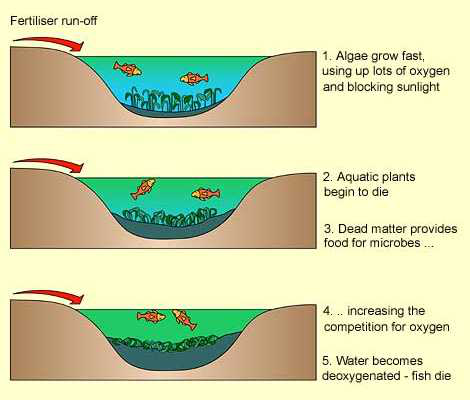

Normally, a natural lake goes through an aging process called eutrophication. It starts with a beautiful young lake and ends as a fertile piece of land. This process in nature is very slow; it takes thousands of years for a lake to disappear. Humans have accelerated this process by adding nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorous) and organic matter by discharging sewage, fertilizers, and detergents into lakes. There are three stages of a lake: oligotrophic, mesotrophic, and eutrophic.

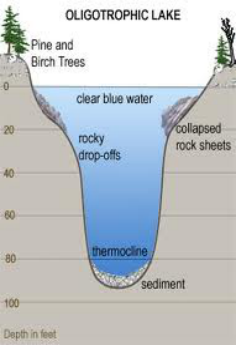

Oligotrophic lakes are young, deep, and clear, with few nutrients. They generally host very little or no aquatic vegetation and are relatively clear. They have a few types of organisms with low populations.

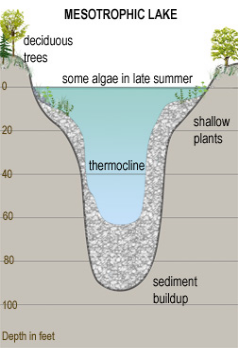

Mesotrophic lakes are middle aged due to nutrients and sediments being continuously added. There is a great variety of organism species, with low populations at first. As time increases the populations increase. At an advanced mesotrophic stage a lake may have undesirable odors and colors in certain parts. Turbidity and bacterial densities increase.

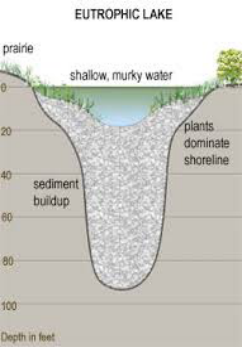

Eutrophic lakes, due to further addition of nutrients, have large algal blooms and become shallower, with fish types changing from sensitive to more pollution-tolerant ones. Over a period of time, a lake becomes a swamp and finally a piece of land.

NATURAL SUCCESSION IN LAKES

SAMPLE PHOTOS

Oligotrophic lake

Mesotrophic lake

Eutrophic lake with blanket weed covering the surface

Factors affecting lentic water quality include temperature, sunlight, turbidity, dissolved gases and nutrients.

Temperature and stratification.

Water has a maximum density (1 g/cm3) at 4°C. Above and below this temperature water is lighter. Temperature changes in water cause stratification, or layering, of water in lakes and reservoirs. During the summer, the top water becomes warmer than the bottom and forms two layers, with the top one warmer and lighter and the bottom one cooler and heavier. In cold regions during autumn or fall, as the temperature drops and the top water reaches 4°C, it sinks to the bottom and the bottom water moves to the top. This is known as fall turnover. This condition stirs the bottom mud and releases the anaerobic decomposition (microbial reaction in the absence of oxygen) products such as sulfur dioxide and other odor-causing chemicals that cause severe taste and odor problems. In the winter too much snow cover for longer time periods can cause oxygen depletion by reducing light penetration, thus the lower rate of photosynthesis. This condition can cause winter fish kill. In spring, as the ice melts, and the temperature at the surface reaches 4°C water sinks once again to the bottom and results in the spring turnover, which, like fall turnover, can cause taste and odor problems.

Light. Light, the source of energy for photosynthesis, is important. The rate of photosynthesis depends on the light intensity and light hours per day. The amount of biomass and oxygen production corresponds to the rate of photosynthesis. The amount of dissolved oxygen (DO) in the lakes is maximum at 2 p.m. and minimum at 2 a.m.

Turbidity. Turbidity affects the rate of the penetration of sunlight, and thus, photosynthesis. The more turbidity, the less sunlight can penetrate which lowers the rate of photosynthesis and consequently less DO.

Dissolved gases. These are mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) and oxygen (O2). Carbon dioxide is produced during respiration of plants and is used in photosynthesis; oxygen is produced during photosynthesis and is needed for respiration of animals. DO is consumed by the microorganisms for the aerobic (in the presence of oxygen) decomposition of biodegradable organic matter. This oxygen demand of the water is known as biochemical oxygen demand (BOD). The more the BOD, the less DO in the water. The more the DO, the better the quality of water. The minimum amount of DO to maintain normal aquatic life, such as fish, is 5 mg/L.

Lotic Water Supplies

Rivers, streams and springs are lotic water supplies.

Factors affecting lotic water supplies are much smaller than those affecting lakes and reservoirs. The only factors affecting running water is current and nutrients.

Current. It is the velocity or rate of flow of water. The faster the current, the better it is. Current mixes the oxygen from the atmosphere and keeps the bottom of the stream clean by washing away the settleable solids. There is more DO and less natural organic matter that would otherwise decompose in the bottom. Thus, due to the current, streams and rivers seldom go anaerobic.

Nutrients. Main sources of nutrients are drainage from the watershed. Heavy rains and drought conditions can also cause serious problems, such as high turbidity and more nutrients.

Surface water supply is the most contaminated supply, mainly due to discharge of sewage, used water, which is the source of waterborne pathogens, runoffs from farmland, which are the source of Cryptosporidium, pesticides, and fertlizers; and industrial discharges, which are the source of a variety of contaminants. Surface water, therefore, needs the maximum treatment for potability (satisfactory for drinking).

Groundwater Supplies

Underground water is supposed to be the purest form of natural water. Sometimes, it is so pure that it does not need any further treatment for drinking purposes. It is the least contaminated and has very low turbidity due to natural filtration of the rain water. It can be contaminated by underground streams in areas with limestone deposits, septic tanks discharge, and underground deep well leaks. Therefore, it may need disinfection. It needs only mineral removal treatment when compared to surface water supplies. It contains more dissolved minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese and sulfur compounds than the surface supply. There are two sources of groundwater: springs and wells.

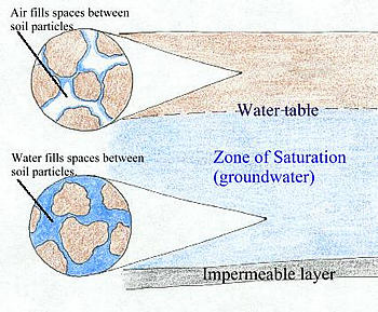

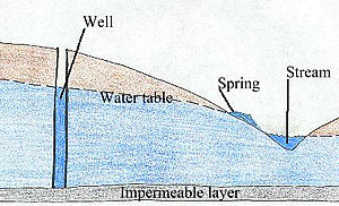

If you dig a hole down through the earth, the soil initially has pockets of air between the soil particles. But as you dig deeper, soon water would fill in all of the gaps in the soil. The location where all of the holes first become filled with water is called the water table. This is the upper limit of the zone of saturation, also known as an aquifer, which is the part of the earth containing the groundwater.

The bottom of the zone of saturation is marked by an impermeable layer of rocks, clay or other material. Water cannot soak through this layer, so it instead slowly flows downhill.

Springs

Whenever an aquifer or an underground channel reaches the ground surface such as a valley or a side of a cliff, water starts flowing naturally. This natural flow is known as a spring. A spring may form a lake, a creek, or even a river. The quantity and velocity of a spring flow depend on the aquifer size and the position of the spring relative to the highest level of the water table. Regions with limestone deposits have large springs as the water flows in underground channels, formed by the erosion of limestone. The quality of the water depends on the nature of the soil through which the water flows. For example, a mineral spring has dissolved minerals, a sulfur spring has dissolved sulfur.

Wells

Public groundwater supply is usually well water because springs are rare. A well is a device to draw the water from the aquifer. Deeper wells (more than 100 feet) have less turbidity, more dissolved minerals, and less bacterial count than shallow wells. Shallow wells have less natural filtration of water due to less depth of the soil.

Small rural communities (less than 25,000 populations) generally use the groundwater from wells. About 35% of the American population uses groundwater supply. Nearly two billion people in Asia depend on groundwater resources for drinking water. In countries like Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, more than half of potable water supply is estimated to come from groundwater (UNEP 2002).

Source:

Lecture from

Introduction to Wastewater Treatment & Disposal) Lesson 2