But it was an Irish aficionado, William Parsons, who, by taking the aperturitis to an unsuspected length, built the world's largest telescope: the Leviathan of Parsonstown.

The town of Birr in County Offaly is located almost in the geographical center of Ireland. At present it has 3,600 inhabitants and in its streets you can see beautiful Georgian houses. Here resides since 1620 the family Parsons, counts of Rosse, reason by which the city was well-known for a long time like Parsonstown.

Entrance to Birr Castle. Photo: © Paco Bellido

The Birr Castle can not be visited, it is still a private residence, today it is owned by William Clere Leonard Brendan Parsons, seventh Earl of Rosse, born in 1936. The current Earl has created a small museum in the castle and has restored his great-great-grandfather's telescope. The visit allows access to the gardens of the farm, the telescope and the museum, which displays an interesting collection of scientific instruments.

Lord Rosse

In 1800 William Parsons was born, who would become third count of Rosse in 1841 after the death of his father. Like his brothers, William studied his early years at Birr Castle, devoting special interest to science and engineering. At the age of 18 he was sent to Trinity College in Dublin and later to Oxford, in England, where in 1822 he graduated with honors in Mathematics.

Portrait of William Parsons, Earl of Rosse.

From 1823 to 1834 he was dedicated to politics, holding a position in the House of Lords. At this time he began to manifest his interest in astronomy, in 1824 he entered the Royal Astronomical Society and two years later he had acquired enough knowledge of optics to begin his experiments in the manufacture of mirrors. In 1836 he married Mary Field, a wealthy heiress of Yorkshire, who would eventually become a great photographer and whose funds helped finance the making of Lord Rosse's telescopes.

The construction of the Leviathan

In the mid-nineteenth century many astronomers thought that Fraunhofer's discoveries had shown that the refractor was unsurpassed and that there was no point in striving to perfect the reflector. Despite this, Parsons dreamed of making a reflector greater than all existing ones. Unfortunately Herschel had never published his manufacturing methods and Parsons had to start from scratch.

Finding skilled workers in the area was not an easy task, so with the help of a competent blacksmith named Coghlan, he formed a team that in a short time handled perfectly the lathes, crucibles and polishers. During seventeen years of experimentation he built a 38-centimeter mirror, then another of 61, and finally in 1840, a 91-centimeter one that was almost as large as the largest one built by Herschel. At that time, glass mirrors were not used, but speculums, a very resistant white alloy formed by four parts of copper and one of tin.

The first problem was to melt the metal mirror without breaking it. He spent five years looking for a suitable copper-tin alloy and, after considering the alloy brittle, he decided to melt the mirrors by separate pieces and then join them by welding and riveting. Then he covered the mirror with heated tin until it melted and then let it cool very slowly.

To shape them, he designed and manufactured a mechanical grinding-polishing machine powered by a steam engine. In the castle museum you can see some pieces of this machine and a scale model.

Scale model of Lord Rosse's mirror polisher. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

The Reverend Thomas Romney Robinson, director of the Armagh Observatory, moved to Birr to test the mirrors. The weather, as it usually does when a telescope is opened, did not help and for several nights they waited until the wind died down and the clouds disappeared. Using high magnification eyepieces realized that the segmented mirror caused problems, this fact led Parsons to opt for mirrors in one piece.

The first Lord Rosse telescopes were mounted on a wooden frame with pulleys, chains and counterweights following the Sir William Herschel design. The frame with wheels was supported on a circular track, which allowed the instrument to rotate 360º and thus be able to point to almost any part of the sky.

Despite the praises of Robinson, Lord Rosse considered these instruments as the necessary first step to undertake the manufacture of the instrument of his dreams, the Leviathan would have twice the diameter of its largest telescope.

On April 12, 1842, the crucibles were started, each seven meters wide. The crucibles were fed with peat, a fuel easy to obtain in the surroundings and from which more than 50 cubic meters were consumed. The metal ingots took ten hours to melt. At one o'clock in the morning the molding process started up: the three crucibles poured molten metal into the mold. He let it cool slowly for 16 weeks, polished it... and it broke just as he was going to put it in the telescope. He had to remelter the metal and in this second attempt he achieved a mirror of perfect shape and brightness. Since the metal mirrors oxidized very quickly, especially in the humid Irish climate, Parsons needed a second spare mirror, after another two unsuccessful attempts he obtained a fifth satisfactory mirror that he would use as a spare.

.jpg)

One of the mirrors of Lord Rosse in the Science Museum in London. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

The mirror, 182 cm in diameter and four tons, was mounted on a wooden tube seventeen meters long, the wooden slats were joined by iron rings similar to a barrel. The telescope was placed between two seventeen-meter-high masonry walls seven meters apart. It was moved by an ingenious system of levers and weights devised by Thomas Grubb in Dublin. To raise and lower the tube was necessary the collaboration of two operators who placed the telescope at the desired height along the meridian with the help of a winch. Another assistant turned it to the sides, which allowed a small adjustment in azimuth between the two walls. A fourth assistant was in charge of raising the observation platform. The tube that had a margin of movement of about 15 ° between the stone walls could not follow an object for more than an hour. The observers had to wait for the object to pass through the local meridian in order to observe it.

The Leviathan of Parsonstown. Photo: © Paco Bellido

They also had to wait for the sky to clear. Possibly Birr is one of the worst possible places to install the largest telescope in the world, only once in a while the sky cleared and there was an atmospheric calm that allowed good views. In the chronicles it is said that the telescope could only be used about sixty nights a year. The tube had no search engine, to locate the objects Lord Rosse used a low power eyepiece that covered a field of more than half a degree. In addition, he could use the eyepieces in pairs, the eyepiece holder had a sliding frame in which two eyepieces could be inserted, being able to exchange the magnifications simply by moving the frame.

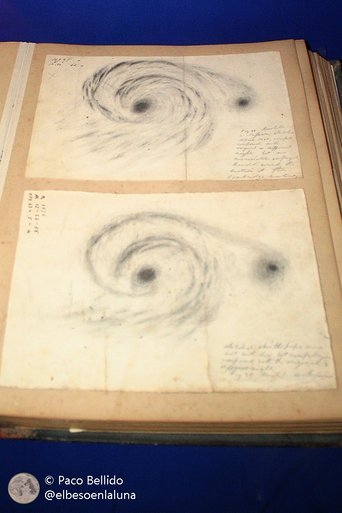

One of the rare nights when the sky was calm, in April 1845, William Parsons observed M51. In the Leviathan it appeared as a majestic spiral beautifully studded with stars, which would be worth the name of the Swirl galaxy. This discovery encouraged him to continue looking for other spirals in the sky but that same year there was the great Irish famine, a crisis caused by the shortage of potatoes and that cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and forced thousands to emigrate. to the United States. As a landowner, Lord Rosse had to face this misfortune and could not resume the observations until 1848.

The spiral nature of M51, one of the discoveries of this giant telescope. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

In 1848, Lord Rosse studied a hazy patch that had been first observed in 1731 by the English astronomer John Bevis and which Messier had ranked number one on its list of objects. Lord Rosse discovered that M1 was an irregular nebula spot with bright filaments that reminded him of the legs of a crab, he called it the Crab Nebula, a name we still use today.

In 1850 he had already identified fourteen nebulae, among others, M77, M95 in Leo and M33 the spiral of the Triangle. Robinson and most of the astronomers of the time thought that they were not independent galaxies, but were part of the Milky Way. Lord Rosse supposed that the spirals were island-universes, an idea already conjectured by Immanuel Kant, and he erroneously sensed that all nebulae, including Orion and the Ring in the constellation Lyra, could be decomposed into separate stars with a telescope. higher.

Lord Parsons discovered between the years 1848 and 1865 with the 72 and 36-inch telescopes 226 objects of the NGC catalog (work published by his son Laurence in Observations of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars Made with the Six-foot and Three-foot Reflectors at Birr Castle From the Year 1848 up to the Year 1878, Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society Vol. II, 1878). Johan Ludvig Emil Dreyer, who would be the compiler of the NGC catalog, discovered another 18 objects thanks to the largest of these instruments; Robert Stawell Ball, another of his assistants, also discovered 11 NGC objects working in Rosse's company with said telescope.

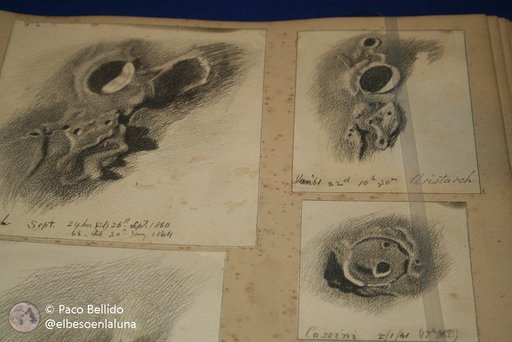

In spite of being more dedicated to the observation of nebulae, they also directed the telescope to the planets and to the Moon. One of the ideas was to compare lunar formations with terrestrial ones, dedicating their efforts to the search for lunar volcanoes. In the museum there are some precious drawings of the observations of lunar craters. In 1852 several members of the lunar section of the British Association raised the possibility of using Leviathan to create a new map of the Moon under different lighting conditions.

Lunar craters drawn by Lord Rosse in the Birr Castle museum. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

One of its last astronomical uses was to confirm, in August of 1877, the existence of the tiny satellites of Mars discovered from the United States by the astronomer Asaph Hall.

The Leviatán telescope is mentioned in the Jules Verne novel entitled From the Earth to the Moon, where he is cited as the world's greatest in his time (1865).

The fourth count of Rosse

Of the four sons of William Parsons, two inherited his father's passion for astronomy. Charles became a famous engineer thanks to the invention of the steam turbine and his works had a great influence on naval and electrical engineering. He was the founder of the company Grubb-Parsons of Newcastle-on-Tyne after buying Grubb's optical workshop, continuing the tradition begun by his father. The firm continued working until the mid-eighties of the twentieth century, having built some of the largest telescopes in the world, including the 98 Newton Isaac Newton telescope currently in the Canary Islands.

Nevertheless it was Laurence, fourth count of Rosse, who more was dedicated to the astronomy. Throughout his life he applied a number of improvements to Leviathan. His greatest discovery was the determination between 1869 and 1872 of the surface heat of the Moon, for which he obtained a value very close to that currently admitted. Since the Moon has no atmosphere, its surface becomes very hot when illuminated by the Sun and cooled in the dark, Laurence Parsons determined that the temperature of the Moon was 119 ° C, the current value is 69 ° C, that contradicted the general opinion that the temperature had to be below zero. To make this measurement, he made a portable telescope with a silver-plated parabolic mirror and a very short focal point in whose focus he placed a thermocouple. Part of the radiation received from the Moon is reflected solar radiation, formed mainly by wavelengths corresponding to the visible spectrum less than 0.7 microns, the rest is direct radiation from the hot moon surface that, as low temperature radiation, is formed by wavelengths greater than one micron. Laurence Parsons found that 14% of the lunar radiation was reflected solar radiation and that 86% was proper lunar radiation, derived from the heat of our satellite.

His results were confirmed by very accurate measurements made in 1874 by Very at the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh, USA, however some astronomers of the time did not appreciate the value of the discovery referring to Laurence Parsons with contempt as "a madman Irish from the swamps ".

The portable telescope with which measurements of the Moon's heat were made can be seen in the museum, as well as a copy of the article in the Royal Dublin Society magazine detailing the results obtained.

The telescope that allowed to measure the infrared radiation of the Moon. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

With the 36-inch telescope he studied the spectra of eleven nebulae and the observations showed that only four of them were gaseous, the rest showed the continuous spectra characteristic of stellar objects. However, the installation of the spectrometer was not ideal and contributed to making the observations more difficult.

The Leviathan today

In 1968 the telescope was in very bad condition, it had not been used for ninety years. That year an exhibition was held in Birr to commemorate the centenary of the death of William Parsons to which the well-known British astronomer Patrick Moore went to give a lecture on the observations made with the Leviathan. Moore had spoken the year before about astronomy at Birr Castle on his BBC Sky at Night program, sparking the interest of many influential people and organizations to restore the telescope. The conference became a small booklet, The Astronomy of Birr Castle, published in 1971 by Michael Beazley.

The Leviathan and the observation platform. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

In the eighties, a good part of the documentary collections that were in very poor condition in an abandoned wing of the castle were restored. Many of the old documents and photographs were essential to carry out the restoration work. In February 1996, reconstruction work on the telescope began, a task financed 75% with funds from the European Union. The work was commissioned to Michael Tubridy, an Irish engineer best known for being part of the music group The Chieftains. Collecting all the pieces of the puzzle turned out to be a detective's own task until they managed to locate the location of the different parts of the mechanism, buried by the passage of time.

The reconstruction of the tube took six months. Only 10% of the original wooden boards and half of the metal bands could be used. In addition to the reconstruction of the tube, the team of restaurateurs had to face other challenges. One of the most challenging was the recovery of the universal joint, a mechanism that supported the entire weight of the telescope in its different positions. After cleaning and tuning it was found that it had withstood the test of time well and that it was not necessary to rebuild it, which was a great relief for the team. Another of the essential pieces was the winch used to raise and lower the telescope. In the docks of Dublin they found one similar to that of Birr that was donated for the restoration project and that after a slight modification adapted perfectly to its new function.

Detail of the eyepiece. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

On February 23, 1997, Irish President Mary Robinson officially inaugurated Birr's new Leviathan.

The Leviathan was the largest telescope in the world from its construction in 1842 until the start in 1917 of the large 100-inch Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson. Technically it was a good instrument that turned out to be practically useless due to the bad weather conditions of Ireland, the difficulty of its handling and the pointed limitations it had. Lord Rosse's telescope allowed observing stars of magnitude 18 and although some scientists were skeptical, like the French optician Leon Foucault who declared that the Leviathan was a joke, many astronomers declared not to have seen in their life better views through a telescope.

Detail of the counterweights. Photo: © Paco Bellido.

Bibliography:

KING, Henry C. The History of the Telescope, Dover, 2003

PANNEKOEK, A. A History of Astronomy, Dover, 1989

TUBRIDY, Michael. Reconstruction of the Rosse Six Foot Telescope, Birr 1998

SHEEHAN, William P. and DOBBINS, Thomas A. Epic Moon, Willmann-Bell, Inc., 2001

ZIRKER, J. B. An Acre of Glass, The John Hopkins University Press, 2006

PANEK, Richard. Seeing and Believing, Fourth State, 2000