During the Silurian and Devonian periods, armored fish known as placoderms appeared, grew to be the dominant class of fish on the planet, and then went entirely extinct during the late Devonian. Placoderms were notably among the very first jawed fish in existence. The relatively slow moving placoderms also possessed thick armor plates on their heads, ranging backwards in some to cover the complete front half of their bodies.

Dunkleosteus skull

Placoderm Jaws and Diet

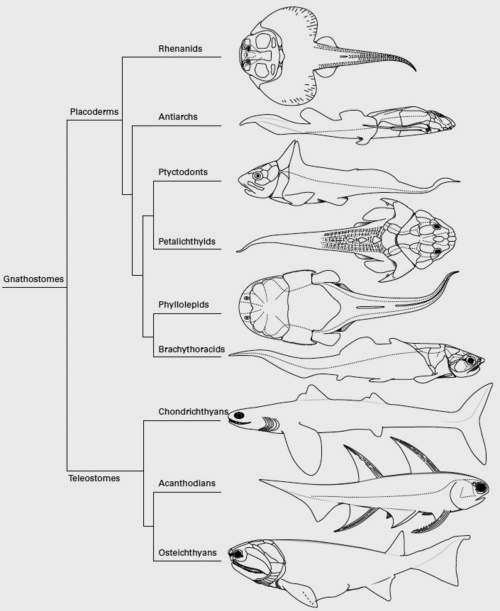

Placoderms make up the earliest branch on the tree of the gnathostome family, which is itself the earliest branch of jawed fishes. Placoderm jaws evolved during the Silurian from bars or arches that supported the gills in more primitive fish. Fish jaws originated among a group of fish known as acanthodians, which seem to have radiated out into every known jawed fish today. Placoderm jaws were for some time thought to lack teeth, though it was later discovered that they in fact were the first to evolve them. Most placoderms, however, had large, beaklike protrusions of bone that could open and close with incredible force. This well adapted them into hunting molluscs, crustaceans, other invertebrates, armored fish, the early sharks of that time period, and even each other. Certain species, including Dunkleosteus, were known to eat even the bony parts of organisms, then spit them back up as boluses.

Unlike many species, the upper part of the jaw moved as well as the lower (the head would tilt up during a bite)- in fact, some species of placoderms had as many as four different types of joints moving in concert during a bite. The upper jaw bone fit inside the lower jaw bone.

Placoderm Armor

Placoderm armor covered the front of the head, and sometimes extended back across half the body. The armor is the most commonly found part of placoderm fossils, being the most easily preserved. The armor plates overlapped one another, providing a wider range of motion for their jaws as well as providing reinforcement.

As much of the rear of the body was unarmored, there have been debates about the original purpose of the armor. It has been proposed that it originally evolved as a defense against giant sea-scorpions present in brackish environments during this time, or as support for external organs.

Placoderm armor and heads grew in an astonishing variety of shapes, from the blunt faces of the Arthrodira to the ray-like fans of Rhenanida to the arrowhead shapes of Petalichthyida.

Bothriolepis canadensis

Bothriolepis canadensis

Placoderm Evolution

Placoderm fossils first appeared in the Upper Silurian and Lower Devonian freshwater deposits. The first placoderms in the Silurian began to radiate quite quickly, due to the major competitive advantages that jaws gave them. By the beginning of the Devonian, all of the major placoderm groups had already evolved. Placoderms took a significant amount of time to move into the ocean, and once there, did little expansion and diversification until well towards the end of the Devonian. During the late Devonian, however, placoderms rapidly expanded out to fill niche after niche, including all of the apex niches.

Despite their thick armor plates, placoderms were actually cartilaginous fish. It was originally thought that they were then out-competed by bony fish, but now it is believed that bony fish did not actively contribute to placoderm extinction.

At the end of the Devonian, immediately before the extinction events began, placoderms had reached their highest level of species diversity, including the best known and most terrifying placoderm, Dunkleosteus.

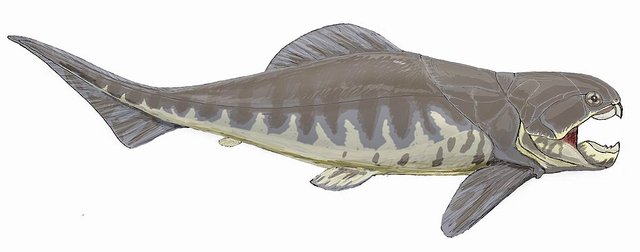

Dunkleosteus

Dunkleosteus was the largest of the placoderms, and among the largest of all organisms in the Silurian or Devonian. It was the apex predator in its environment, unchallenged by any but other Dunkleosteus. A member of the Arthrodira, the largest order of placoderms, Dunkleosteus grew 8-11 meters in length (26-36 ft). The only creature in the water during this period that could challenge the largest species, Dunkleosteus Terrelli, in size other than other Dunkleosteus was Titanichthys, another placoderm which was assumed to be a filter feeder rather than a predator. The next largest species of predatory placoderm contemporary to Dunkleosteus was likely Gorgonichthys clarki, which grew up to 6 meters in length.

Dunkleosteus had one of the strongest bites of any animal in history, capable of delivering over 6000 N of force at the tip of the jaw and over 7400 N with its rear dental plates. It was strong enough to bite through the armor of other placoderms, and there has even been Dunkleosteus armor found with scrapes and cuts that match the jaws of Dunkleosteus. If a Dunkleosteus was alive today, it would be capable of biting a great white shark in half. The jaw could also open with extreme speed, which would actually create suction to drag its prey into its mouth, meaning that Dunkleosteus likely didn't pursue prey with its mouth open like a shark, but instead only opened it at the last minute, sucking its prey into its jaws. Suction feeding is still a successful evolutionary strategy to this day.

Dunkleosteus

Dunkleosteus

Placoderm Extinction

The placoderms went extinct at the end of the Devonian. During the Kellwasser event, the first of the mass extinctions at the end of the Devonian, approximately 6 of the 14 families of placoderms went extinct. The others, including Dunkleosteus, survived all the way until near the end of the mass extinctions, finally being wiped out completely in the Hangenberg Event, which marked the end of the Devonian. The Hangenberg Event was an anoxic event, that is, it caused oxygen levels in the oceans to drop precipitously. Simply speaking, the placoderms and many other species of fish were unable to breathe. It has been linked to an abrupt shift from greenhouse to icehouse climate conditions globally, along with a global aquatic transgression. Black shale was deposited all over the world during this event. The global cooling of the period has been linked to the rapid radiation of terrestrial plants- the first vascular plants evolved during the Silurian, and rapidly began to spread. Along with the placoderms, trilobites, many reef-building organisms, and some ammonoids were also wiped out.

Lunaspis broili

This post received a 4% upvote from @randowhale thanks to @mountainwashere! For more information, click here!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hey man very interesting post.

Id like to nominate it in OCD.

This gem of a post was discovered by the OCD Team!

Reply to this comment if you accept, and are willing to let us share your gem of a post! By accepting this, you have a chance to receive extra rewards and one of your photos in this article may be used in our compilation post!

You can follow @ocd – learn more about the project and see other Gems! We strive for transparency.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Absolutely, I'm a big fan of OCD!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Very interesting........those water scorpions sound scary, too.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Lots of scary stuff in the oceans in past geological epochs.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I am passionate about archeology, artifacts, the evolution of life and things like this, and I really like your article.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Glad to hear it! I'll be posting a lot more like it!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This post recieved an upvote from minnowpond. If you would like to recieve upvotes from minnowpond on all your posts, simply FOLLOW @minnowpond Please consider upvoting this comment as this project is supported only by your upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit