Luuc Kooijmans investigates crafted by Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch, known for his striking 'still life' shows which obscured the limit between logical safeguarding and vanitas craftsmanship.

When going by Frederik Ruysch in Amsterdam in 1697, tsar Peter the Great kissed one of the examples from his anatomical exhibition hall, and a while later purchased the whole accumulation. Three hundred years after the fact, the Dutch crown sovereign, Willem Alexander, when going by St Petersburg, was withheld from seeing Ruysch's work. Representatives had chosen the ruler must be saved seeing the 'shocking, disfigured embryos' that Ruysch had safeguarded.

In the event that he had heard this, Frederik Ruysch would have turned in his grave. Not that he would have been shocked to hear that his arrangements had survived three centuries, for he would have expected nothing less. Nor would he have been amazed to discover a sovereign appreciating his work. In any case, he would have been unnerved to hear his examples depicted as horrifying, since it was absolutely the excellence of his arrangements that earned Ruysch dependable popularity. For quite a long time, companion and enemy alike have concurred that he ought to be credited, most importantly, with making life systems a satisfactory interest.

Toward the start of Honoré de Balzac's novel La Peau de Chagrin, the youthful hero is meandering around Paris, intending to put a conclusion to his life, when he chooses to go into an oddity shop. There he experiences what Balzac depicts as a 'captivating animal', the treated body of a kid, which helps him to remember his glad childhood. This 'dozing' kid ends up being a remainder of the gathering of Frederik Ruysch, who had been dead for precisely a century when Balzac composed the novel.

The Italian creator Giacomo Leopardi did not discover the arrangements alarming either. In his 'Exchange of Frederick Ruysch and His Mummies', Ruysch is stirred at midnight by his bodies, who have sprung up in his studio and are singing in chorale. Ruysch, viewing through a break in the entryway, shouts, 'Great sky! Who on earth instructed music to these dead individuals, who are crowing like chickens amidst the night? I'm in a cool perspiration and more dead than they are. I didn't understand that since I spared them from rot they would return to life.' He at that point enters his studio and says, 'Kids, what sort of diversion would you say you are playing? Have you overlooked that you're dead? What's this racket about? Has the tsar's visit gone to your head?' One of the dead discloses to Ruysch that they can represent a fourth of 60 minutes, so he approaches them for a concise depiction of what they felt when they were wasting away. They guarantee him that diminishing resembles nodding off, similar to a dissolving of cognizance, and not in any way excruciating. They announce that passing, the destiny of every single living thing, has brought them peace. For them, life is nevertheless a memory, and in spite of the fact that they are not cheerful, in any event they are free of old distresses and fears.

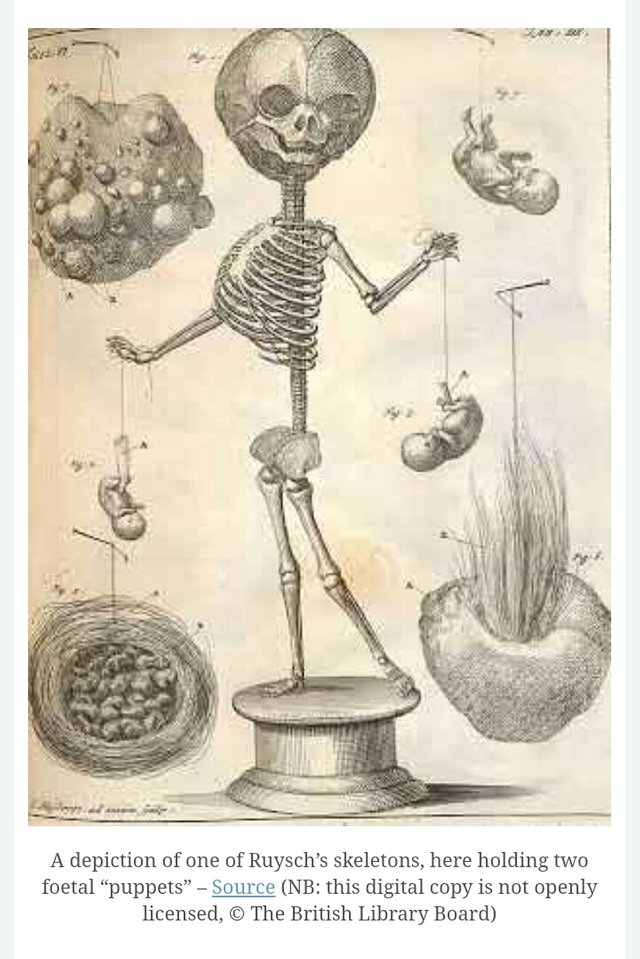

Ruysch's fundamental trap was warming white wax, and infusing it into veins in fluid frame. When it cooled and set he would have a dissectable arrangement. By recoloring the wax red he figured out how to give bodies and organs a similar tint. The outcome was stunning. He utilized his arrangements in showing specialists and birthing specialists, yet there was such a great amount of enthusiasm for them that he set up a display. It was the first occasion when that individuals could appropriately observe human interior organs. The display before long turned into a noteworthy fascination.

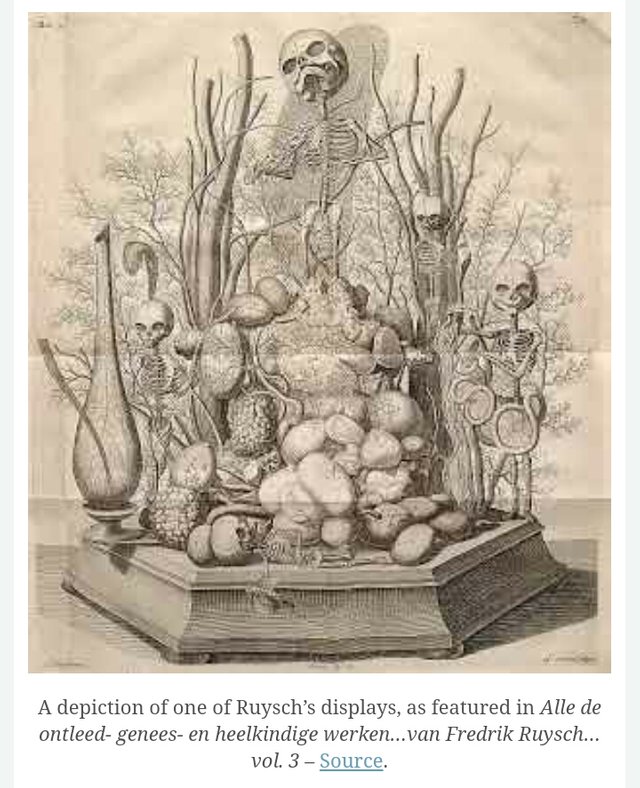

The historical center was more than basically an accumulation of anatomical proof. The individuals who entered were promptly stood up to with a tomb containing different skeletons and skeletal remains. Among them was the skull of an infant put in a case, beside a sign with the proverb: 'no head, anyway solid, escapes remorseless passing'. The tomb likewise contained the skeleton of a kid of three, holding the skeleton of a parrot, which had been set there as a reference to the adage 'time flies'.

In spite of the fact that the admonitory inscriptions were particularly in the built up custom of anatomical introduction, the gallery was very one of a kind in that Ruysch had endeavored to give it an appealing plan. In the midst of the little skeletons in the tomb, for example, was the preserved body of an embryo of seven months. Its very characteristic shading officially made the sight somewhat less repulsive, yet Ruysch had decorated the kid in different courses too, by putting a bunch in its grasp and crown of blossoms on its head. The blossoms, as well, had been protected with the goal that they would keep their petals and their brilliant shading.

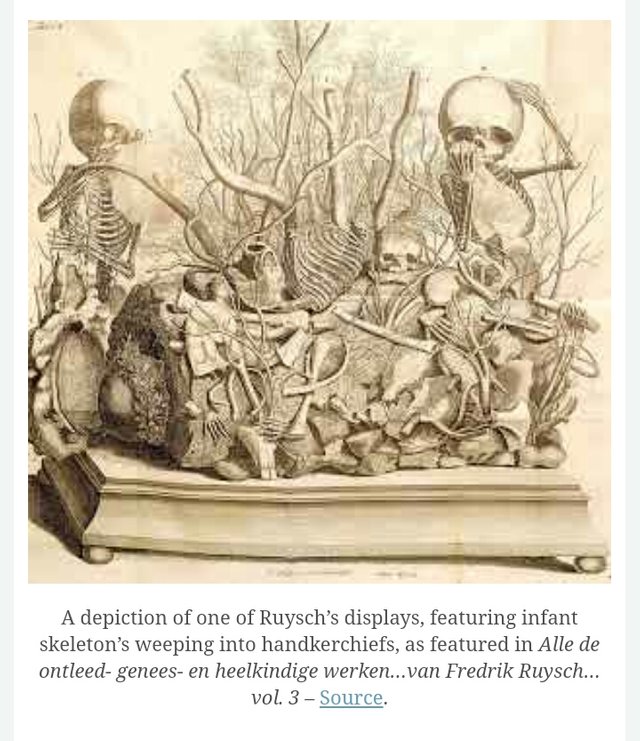

Guests were gone up against with the skeletons of an offspring of four with a toy in its grasp, a five-year-old holding a silk string with a treated heart dangling from it, and a young lady drying her eyes with a pocket tissue.

Improvements, keepsake mori pictures and vanitas images put the loathsomeness of death in context by focusing on the short life of life, by demonstrating that the body was close to a natural casing for the spirit. After death it never again filled its need – just an anatomist could even now make it valuable to the living.

Obviously, the genuine objective of the anatomist was not to astound his group of onlookers, despite the fact that that desire, as well, could be defended, especially by belligerence that it would inspire the watcher with the wondrousness of God's creation. Be that as it may, a definitive target of life structures was to build man's learning of the structure and workings of the human body. Ruysch had built up his abilities to have the capacity to make structures noticeable which would some way or another have stayed undetectable.

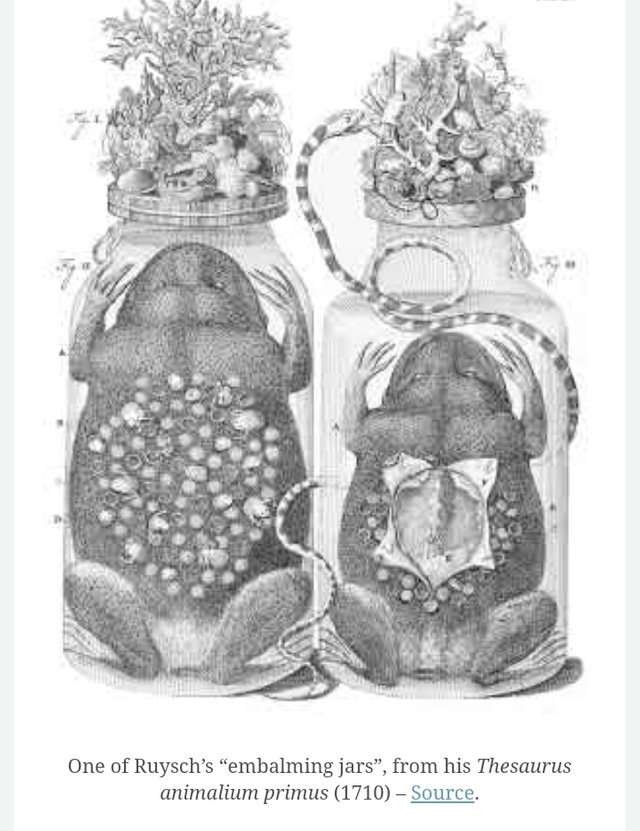

Towards the finish of the seventeenth century, following thirty long stretches of training, Ruysch, helped by his child, figured out how to culminate his planning technique, which, as he stated, now made 'the most diminutive parts of the human body clear to the eye'. Key to the procedure was the infusion of a substance that would not coagulate until the point that it had infiltrated the most modest of veins. Fluid wax went a reasonable route towards this goal, however not the extent that Ruysch needed. So he had continually been searching for a superior substitute. When he had that, he made numerous new anatomical revelations, and he could make arrangements that contrasted little in appearance from living tissue. The majority of them presently were put away in glass jugs and containers, in an astoundingly clear fluid he called alcohol balsamicus, a fluid that protected their similar shading and versatility. While they used to end up hard and firm, and lost their shading, now they were kept splendid and supple

At the point when Ruysch first made his outcomes open, his procedure was viewed as similar to magic. A few people essentially declined to trust their eyes. Ruysch was blamed for utilizing dishonesty to make his arrangements more appealing. He was frequently censured for the way he introduced his anatomical material. What was the purpose of all that frivolity, he was asked, and he countered by requesting to know why individuals spent so much cash covering bodies that were at that point worm-eaten. His reasons were clear: 'Most importantly, I do it to alleviate the aversion of individuals who are normally disposed to be disheartened by seeing carcasses', he stated, however (and this was the reason he would not like to be blamed for shameful moves) he additionally observed an unmistakable association between the presence of his arrangements and their logical legitimacy, for he asserted the capacity to reestablish a body to the state it was in before death. That his bodies appeared to be snoozing was not simply astonishing, it was likewise noteworthy.

Since his new procedure empowered him to work all the more productively and to improve and more lovely arrangements he chose to rearrange his historical center, and in doing as such, he focused like never before on the introduction. The gathering was set in various cupboards that filled three rooms. As previously, the course of action was not methodical: Ruysch turned each bureau, which he called a thesaurus, a storage facility of information, into an individual gem, comprising of various types of arrangements in one of a kind mixes. The focal point of each bureau was an anatomical still life put on a bed of bladder-, kidney-and rankle stones, from the middle of which rose 'trees' of dried veins loaded with a red wax-like substance. Among these stood little fetal skeletons. Regardless they conveyed their grave message to the guest, however at this point they did it with a comical inclination

Such a mix of earnestness and diversion fits in with a long-standing convention. Sixteenth-century distributions possessed large amounts of delineations of skeletons utilizing bones as drumsticks. As it were, Ruysch's creations were inconspicuous, three-dimensional forms of those anatomical outlines indicating skeletons in emotional stances put in inquisitive settings. Various distributions on life structures – the well known map book of Vesalius, for instance – contained pictures of skeletons depicted as undertakers, or hanged offenders. Be that as it may, to show skeletons as characters in a scene non vivant was very uncommon, and a sign of the degree to which Ruysch had removed himself from his material. In one of his creations a skeleton says: 'even after death I'm as yet alluring!'

Despite the fact that the gathering mirrored his scan for answers to logical inquiries, and could be utilized to answer such inquiries – in any event when Ruysch could discover the readiness he was searching for – it was to a great extent an end in itself. Ruysch did not arrange his work as per particularly figured issues. Rather, he kept himself to portraying his accumulation and recording the perceptions his infusions had empowered him to make.

He kept up that he was just satisfying the longing to watch the supernatural occurrences of God Almighty, however in truth his inspiration was twofold: not exclusively did he lift up the human life structures as a wondrous result of creation, yet he introduced himself as a veritable craftsman of death. His show of his anatomical virtuosity contained the hidden message that he – and only he – could resist