In late May, Brussels has a sizzling smell. In the European Parliament building at the Schumann Square, Zuckerberg dressed up and tried to squeeze a smile. "Face has always been to Europe." He is receiving questions from lawmakers about the Cambridge analysis incident. "User privacy has always been It's the focus of Facebook work, but we can do better."

Speaking with humility and evasiveness when answering, from tone to strategy, were all the same as when he was questioned by the US Congress six weeks ago. The reason why he was questioned - that large-scale data leakage event that may have affected the outcome of the US election - has pushed the world's attention to data protection to a small climax. People are beginning to realize that technology companies are likely to treat personal data only as profitable raw materials rather than assets that need protection, and this needs to be corrected.

This time, in Europe, Zuckerberg may not be so easy to pass.

Three days after the end of the parliamentary inquiry, on May 25, 2018, a data protection bill known as "the strictest in history" was issued from Brussels and was fully implemented in the EU. The bill, named GDPR (Translated as the General Data Protection Regulations), has attracted the attention of all parties long before it came into effect, because of its strict regulations, wide scope of application, and high fines. As the date approaches, emails are being screened by authorized emails from various types of data companies. It seems that this is also an indication that a whirlwind in the digital age is coming.

The strictest in history, where is Yan

"One of the most important principles of GDPR is that wherever there is data, there must be protection. If there is no national border in digital space, then protection also has to follow the data, not just the EU's borders." Member of the European Commission, Vera Chu Věra Jourová told reporters that the European Commission on Justice, Consumer Rights, and Gender Equality, which she heads, led the legislative process of GDPR. She stressed that "in the EU, privacy is a basic human right."

The GDPR guided by this principle shows more stringent appearance than the previous data bills. "The most prominent is giving unprecedented rights to individuals who are the subject of data." Data protection law expert Christopher Kuner told reporters on the interface that he is currently a member of the Commission's GDPR task force. He believes that the protection of individual rights stipulated in the constitutional level, together with the emerging privacy threats in the digital era, is the fundamental driving force behind GDPR.

These rights are reflected in: In addition to broadening the scope of “personal data” and explicitly protecting personal privacy “data portability” and “right to be forgotten” into the law, GDPR also emphasizes the importance of data protection.” The territory "changes to "personality." This means that the scope of application of the Regulations is no longer confined to the territory of the European Union. Any enterprise that provides goods services to the EU market and collects or processes personal data is subject to jurisdiction.

Undoubtedly, this puts high demands on companies engaged in data collection and processing and their industrial chains.

The GDPR stipulates that both the data controller and the data processor must collect and process information in a legal, fair, and transparent manner, and must explain the way the data is collected to users in a common language. Obligation to take steps to remove or correct incorrect personal data.

The GDPR also stipulates the method of data exchange among enterprises: allowing EU enterprises to exchange data within the group, but if data is to be transmitted outside the EU, certain conditions need to be met, for example, the place must belong to the European Commission to determine “with proper data protection. "Level" of the area. In the event of non-compliance, all parties of the data supply chain will be accountable from top to bottom.

The GDPR also made suggestions for the manpower of the company: Regardless of whether it is an EU enterprise or not, if there are more than 250 employees in the EU, it is necessary to hire a Data Protection Officer. The 28 member states of the European Union have established the Data Protection Authority, a regulatory agency, which will monitor the implementation of GDPRs in various countries. In case of illegal business, the maximum amount of the penalty can be up to 20 million euros or 4% of the company's annual global turnover (whichever is higher).

It is worth noting that not only enterprises but also the government is under the jurisdiction of GDPR. As the "public authority" handling personal data in the EU, the government is one of the actors in the GDPR regulations. Zhu Luowa told the reporter that the main goal of GDPR also included restricting the collection and use of personal data by the government. “We need to let the government control the citizen data less, not more.” Zhulova said, “We ( The EU hopes to gradually extend this set of standards to the United States. Of course, the FBI and CIA may not be happy."

The first landing, why is the EU

GDPR is not written in one day.

“For Europeans, privacy has always been important. GDPR is only the last step in this long accumulation.” Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, a professor at the Institute of Cyber Studies at the University of Oxford, told the interface reporter, “ This has historical reasons. In the past, dictators used the personal data they controlled to kill innocent people.” He pointed out that during World War II, Nazi Germany identified Jews and tried to genocide. Another well-known identity of Ziberger is the defender of the "right to be forgotten" and he also has several bestsellers on digital ethics.

In Europe, discussions on data protection began as early as the middle of the last century, and legislative practice can be traced back to Germany in 1970 when the Hessian State promulgated the world’s first law specifically for personal data protection. By 1995, the European Union issued the "EU Data Protection Directive" (abbreviated as the "95 Directive"). This is the first data protection law for the entire European Union and has been used up to now. After May 25, 2018, the "95 directive" will be replaced by GDPR.

According to lawyer Feng Jianjian, the "95 directive" abdicated because it could not continue to adapt to the new requirements of the digital age. In the year of 95, the network technology was only aimed at the automation of computer data, mainly the two functions of information release and transmission. "At the time, the Internet was only a prototype. Although the '95 directive' was a good bill at that time, it certainly did not consider the mobile Internet and the Internet of Things will develop as it is today." He told the reporter. Feng Jianjian has many years of experience in data compliance and cross-border investment business. Now he is a partner of Jingtian Gongcheng Law Firm's Shanghai office.

After entering the year 2000, the rapid development of science and technology has brought new cases of digital infringement, and the “prism door” has also triggered new concerns about government monitoring. Thomas Poell, a communication scholar, shared one of his studies: Today's society is a “platform society,” and users and data are constantly gathering on big platforms such as Google and Facebook, in addition to bringing huge commercial benefits to the platform. It also gave them increasingly unconstrained power. After this round of digital shuffling, the power structure was reorganized and it was time to enter the stage of "platform society" control and control.

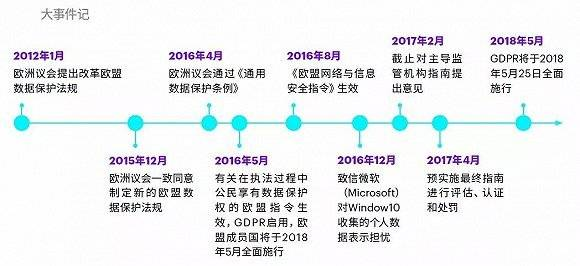

In order to catch up with this trend, the European Parliament proposed to reform the EU data protection regulations in January 2012, passed GDPR in April 2016, and gave a two-year transition period to May 2018.

In the system of EU law, directives and regulations are two different legal forms: Directives do not apply directly to member states, but also need to be transformed by member countries into domestic laws. Member states are involved in the conversion process. China has a certain degree of discretionary power, and the regulations have direct effect on the member states.

Kuna pointed out that from the "95 Directive" to the GDPR ("General Data Regulations"), it not only reflects the EU's determination and intensity of data protection is "the most strict in history", but also the pursuit of the "single digital market". . “The EU has always hoped that the internal digital market can be unified. Now it starts with data protection, integrates all member countries, internal data can flow, and there is a unified law out of problems. This is the first step in simplification. Kuna said.

Protection and development, how to balance

For a long time, China’s industry seems to have an understanding of the EU that the EU’s strict protection of data, especially personal data, has limited the development of the data industry and even the entire Internet industry, resulting in the EU countries’ lack of competition in the Internet industry. Force is far behind China and the United States.

In the European industry, a critical voice comes from the artificial intelligence industry that has recently been strategically focused. John Thornhill, the European editor of the Financial Times, once pointed out that "by limiting data flow and increasing legal risks, GDPR will bring a cold wind to the artificial intelligence industry. If data is an algorithm that requires large amounts of feed, then Europe may It is being rationed to supply its most valuable commodities... Chinese AI companies that are almost completely immune to privacy concerns will have original competitiveness in the use of massive amounts of data."

In Feng Jianjian's view, this understanding has its short-sightedness. After carefully studying the cases of data sharing between EU enterprises, he concluded that the core of data sharing is trust. Strict legal protection can establish enough social confidence that the data can be flowed at the level of the enterprise and there will be room for new products and industries. This is an entire virtuous circle of ecosystems. In Europe, the overall level of trust is stronger than in China, and data sharing can therefore be preceded.

A survey by Accenture Consulting in 2016 confirmed this: 83% of respondents believe that trust is the cornerstone of the digital economy. Roland Busch, a Siemens CTO, earlier told an interface reporter that GDPR could provide a “meaningful and thoughtful” guidance to companies like Siemens, which is beneficial to the ecology of the industry. .

“If you look at the logic of GDPR, you will find that there are two conflicting values throughout: protecting the rights of individuals to data, and ensuring that data can legally flow freely.” Feng Jianjian pointed out that the public and the media are seeing more protection. The orientation of personal data rights, because often the data leak events and produce bad results to win the attention; the free flow of data is actually ignored.

For example, GDPR stipulates that users have "data portability", which is an innovative right. It not only gives the user the right to obtain and reuse relevant data, but also gives the user the right to transmit such data. For example, users can ask Facebook to pack all their Facebook data into a format that can be used by Twitter, Linkedin, and Weibo. When they leave Facebook, they can take it away, transfer it to another platform, and continue using it. In Feng Jianjian's view, although this is a great challenge for companies, there are no good practices on how to land them, but it may have a profound impact on promoting the free flow of data.

"What the European Union is doing now is to repair the data protection dams very high. Other countries have to follow suit. The EU just wants to play with countries that are doing as good as I do." Feng Jianjian views GDPR as such influences. As mentioned earlier, the European Union has identified more than a dozen countries and regions with “appropriate data protection levels”, and they are not restricted when conducting cross-border data transmission; while those who are not on the list need to meet more stringent conditions. . China is still not on the list.

The French Open is a grand, difficult point in the implementation

A number of Chinese and foreign academics and industry professionals who have contacted the interface journalists have a basic attitude toward the GDPR outlook: cautiously optimistic.

"Almost no one will specifically and unequivocally oppose GDPR. Its benefits to individual freedoms and social norms are self-evident. But if you go to investigate now, almost any organization can find that it is illegal," Kuna said.

This is a footnote to the complexity of GDPR. There are 99 mainstream GDPRs, which are complicated in terms of the subjects and matters they govern. They involve the internal manpower, legal affairs, IT departments, and involve many links in the industry chain. They also include many groundbreaking and experimental laws. It is no easy task to completely complete compliance.

Hiring a professional who knows GDPR and establishing GDPR compliance for the company is encouraged. According to the reporters on the interface, the cost of GDPR compliance depends on the size of the company and the complexity of the data business, and it can be as low as RMB 100,000 or as high as tens of millions. "For large companies, these costs are nothing. They can even afford a whole GDPR team. But it is not easy for SMEs." Chen Hongjuan, a senior legal adviser in the Netherlands, told the reporter that the EU is making laws. It did not take into account the compliance costs of SMEs, which would make them more vulnerable to competition. Compliance itself constitutes an obstacle to entry. There is the suspicion of strengthening old companies and curbing SMEs. This is another aspect of GDPR being criticized.

The nature of GDPR's ability to take effect outside the EU also invites doubts about the possibility of extraterritorial law enforcement. In principle, the EU law still has binding force on the subjects outside the domain and can issue a ticket, but how to implement it remains doubtful. Feng Jianjian said that mainly rely on the attractiveness of the EU market. Once it violates regulations and refuses to pay fines, it will be very difficult for the company to go to the EU to develop its business. It would be a complete abandonment of this market. "The EU market has a population of 500 million people with low spending power, but companies that do a little bit of international business cannot possibly ignore the impact of GDPR." Feng Jianjian pointed out that other advanced economies in the world, such as Australia, Singapore, and the United States, are currently also Are doing the corresponding data protection work.

Limberg, who has been concerned with data legislation for many years, recalled that he had gone through the “95 Directive” legislation more than 20 years ago. "There was also a similar discussion at that time, thinking that the decree could lead the global privacy discussion. To a certain extent, it does have an impact, but it is far lower than the expectations of European privacy defenders." Hey Berg said.