The success of modern science in many areas has spread the notion that ever-advancing technology will enable us to solve all of our most pressing problems. And yet, on the remote outer islands of Micronesia, it is the rekindling of age-old traditional wisdom that could hold the key to sustainable ocean management. The people of the outer islands depend on fish from their coral reefs for daily sustenance. However, their present and future well-being is critically threatened by unprecedented environmental and cultural change.

In 2010, the people of Ulithi Atoll recognized rapid decline in fish populations from the surrounding reefs. They asked for help in understanding this threat to their survival. Led by marine ecologist Nicole Crane of Santa Cruz, California, a team of scientists came together to respond to the outer islanders’ plea for assistance. Crane’s previous work with communities around the globe to sustain, manage, and revive local fisheries provided a framework for the revolutionary approach they would develop in Micronesia—an approach that combines modern science with the outer islanders’ time-honored techniques of ecological management.

Crane appreciated that the people who have called the islands home for thousands of years know far more about the problems they face than she and her team of biologists and ecologists could learn in a lifetime. She also knew from her prior work that people who have been living sustainably in one area for such a long time will have developed indigenous methods of management that efficiently balance the complex systems that support them. Over generations they have created sophisticated traditions, taboos, and myths around fishing and access to the reefs and their bounty.

“We need to have a common understanding around management, so that everyone agrees and supports it. Understanding the old ways, and the impacts of the new ways, can help us protect the ocean for our children, and their children. We need to do this, its making a difference.” - Isaac Langal, Chief on Asor Island, Ulithi Atoll

The people of the Micronesian Outer Islands speak a patchwork of dialects, each with an oral rather than a written tradition. Crane’s team gathered myths and legends from the islanders, seeking out the elders of the community to relate tales of the distant past. Using conventional ethnographic techniques, they interviewed community members about how they used to fish, in contrast to how they mostly do it now. From these collected narratives they were able to paint a vivid picture of ecological and cultural collapse that could be traced back to World War II.

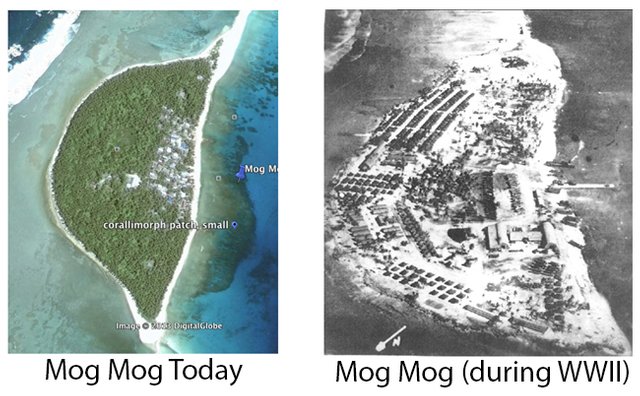

During WWII every tree was cleared from Mog Mog to make room for R and R facilities for service men and women.

During the final year of the war, the tiny islands of Ulithi Atoll served as a major staging area for the U.S. Navy. Local populations were moved to a single island while their former homes were flattened and defoliated beyond recognition, all in order to make room for huts to house the 8,000 service men and women belonging to the 720 ships occupying the lagoon. Of course, such a profound alteration of the islands had unimaginable ecological impact. After the war the United States entered into a compact agreement with the outer islands, bringing temporary prosperity to their inhabitants in the form of aid, food, and supplies.

For the local populace, the war represented a massive cultural and ecological upheaval. Traditional food was replaced by a diet of Spam and other canned meats, along with white rice, and white sugar—a diet that impacts the health of islanders even today. Large numbers of young people left the region to go to school, many never to return. Elders stopped passing on age-old cultural knowledge because many young people who remained no longer valued such traditions. Cultural breakdown in turn precipitated a breakdown of the traditional management techniques that had sustained the reefs for countless generations. As the myths and traditions associated with local supervision of reef biology began to disappear, modern Western fishing technology permitted the exploitation of resources that had once been too difficult, distant, or taboo to access. With U.S. federal aid, the islanders were able to purchase motorboats and a surplus of fuel to replace traditional fishing canoes, while spear guns and nets replaced over 78 diverse fishing methods.

As the compact agreement with the United States comes to a close, the initial prosperity is waning. Because fuel is now scarce and expensive, areas closest to boat landings are over-exploited. Neglecting the traditional fishing methods that targeted specific fish at specific depths, seasons, and sizes, native fishermen intensified the catching of only certain species of fish—until only a handful remained within the reef.

Coral is not just the substrate for a reef ecosystem but a vital participant with a major role in fish diversity and populations.

Another task of the science team was to re-educate the islanders about local reef ecology. For example, herbivorous fish promote coral health, and a healthy reef means a habitat for many types of fish. But when herbivorous fish are depleted by excessive spear fishing, the reef begins to degrade and other food fish disappear. Crane and her colleagues explained this story of imbalance to the islanders—along with others that link cultural and technological changes to the ecological changes that now jeopardize their food supply.

Of course, as both scientists and communities realize, traditional eco-management methods cannot work precisely as they did in ancient times; they must be adapted to a modern context. But the cultural renaissance that hit Hawaii a decade ago has migrated to the outer islands, whose people are now finding novel ways to reconnect to their roots and reinvigorate the customs of a by-gone era.

Today, island communities are formulating management strategies unthinkable only a few years ago. They are instituting no-take areas and autonomously managing their own reefs using long-established traditions as a framework to guide them. Data recently collected by Crane and her team indicate that these autonomously managed zones have indeed recovered significantly from previous years. As of Spring 2014, three of the four islands of Ulithi Atoll have adopted new management planning, with the fourth beginning such planning this past summer. And in July of 2014, the islands of Ulithi hosted a historic gathering of outer island communities.

2014 Summer Workshop

This workshop brought together 75 community leaders from all fifteen islands to discuss the critical issues of food security, cultural integrity, and the effects of climate change. They shared data concerning recent ecological changes, how the breakdown in traditional management played a role in reef deterioration, and how the introduction of more impactful fishing methods has had a drastic effect on the health of the reef system. Participants left the workshop more informed about the threats to their communities and armed with some strategies to combat these threats—strategies not for the incorporation of “new technology” but for encouraging people to reach back into their history and rekindle ancient ways grounded in balance and sustainability.

In future posts I will share the details of our work and how they can serve as a model to other communities that rely on their local environment for their sustenance. I have tons of great photos and stories from the islands. I'll touch on the challenges the Micronesian Outer Islanders continue to face, and the story of their survival through Super Typhoon Maysak in April of 2015. Our 2016 field season has just closed so we return with plenty of fresh data and stories to share! The good news is, it's working, but we have much more to do to help these unique communities not only survive but thrive!

(Any Steem generated by this post, and my future posts about our work in Micronesia will go to the direct aid of people of Ulithi Atoll! You tell me what you'd like to provide! They are in desperate need of water, food and building supplies. This platform could be an important key to secure vital resources to rebuild, replant, and replenish their lives after Typhoon Maysak! We are all One People One Reef! )