Stories in Science

Because scientific research is usually presented impersonally, it's easy to forget that there's an incredible amount of toil, frustration, and excitement behind every single discovery. And the story of a discovery doesn't just end after a paper is published, it continues to grow so long as similar research is being done. This post will tell the story behind some unusual research and investigate a question raised by its findings.

Shulgin: A Prolific And Unorthodox Chemist

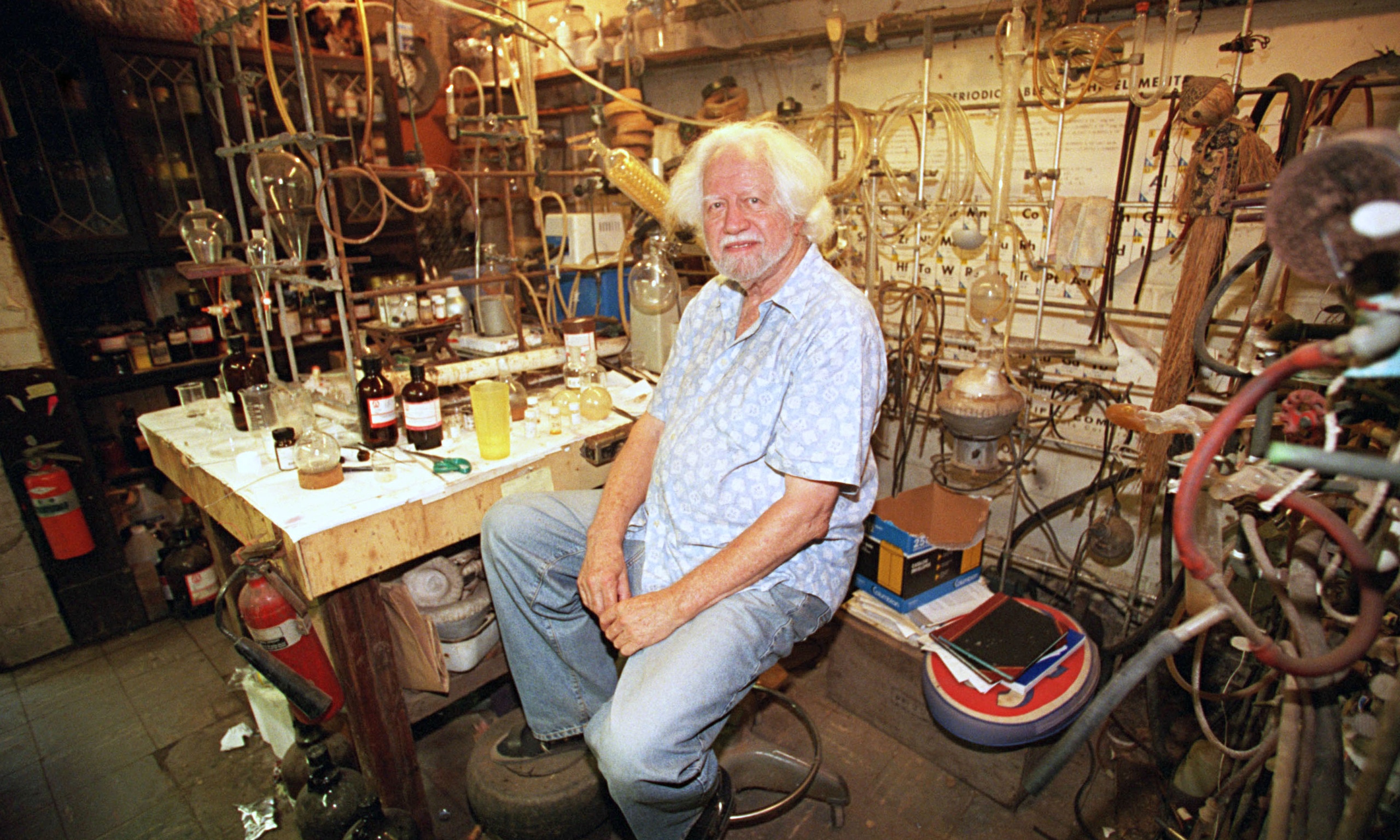

Dr. Alexander "Sasha" Shulgin (1925 - 2014), was an incredibly productive scientist. While he enjoyed success as an industry chemist, he left his job in 1965 to pursue independent studies in a laboratory he built behind his house in Lafayette, California. His research was fair from mainstream chemistry: it entailed him inventing new psychoactive drugs and testing them with himself, his wife, and his friends.

Alexander Shulgin, aged 76, in his laboratory (2001). Source.

If this whole thing seems ridiculously dangerous and illegal, that's because it absolutely would be. Yet for over 20 years, Shulgin had a strong relationship with the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), where he regularly gave talks to agents and even wrote their definitive texts on pharmacology. In return, the DEA awarded him several service plaques and gave him a research license to produce Schedule I drugs, which are the most highly restricted substances in the US.

With his license, Shulgin invented and tested over 230 unique drugs. Keeping rigorous notes, he eventually published a book detailing how each one was manufactured, and what its effects were. In 1994, two years after publishing a compilation of this work, he had drawn too much of a public eye to his controversial research and questionable self-experimentation. The DEA raided his lab, fined him for breaching license terms, and revoked his research license.

While Shulgin's research was shut down, his work continues to heavily influence pharmacological research through his inventive methods and informative publications. Today, we look at one notable compound that Shulgin invented, DiPT.

DiPT: A Pitch-Distorting Drug

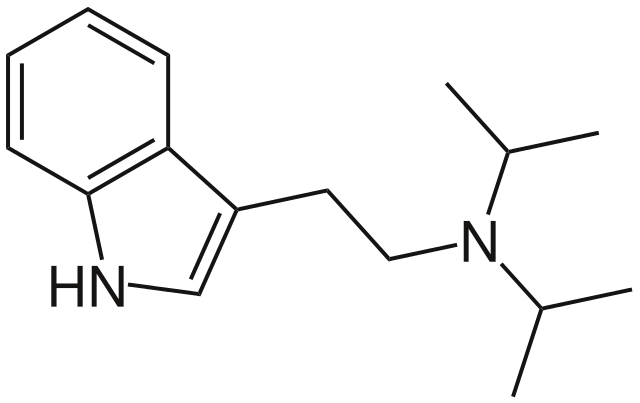

Most of the 230 drugs Shulgin invented were hallucinogens, and DiPT is no exception. But while DiPT is structurally similar to traditional hallucinogens, which tend to cause visual distortions, DiPT does not affect a person's vision. Instead, it changes the pitch and tone of what is heard. For example:

"There was a decrease in high frequency acuity with an unusual tonal shift of all frequencies to a lower pitch... All familiar sounds became foreign, including the chewing of food. No effects were noted with respect to clarity of speech, and both comprehension and interpretation were normal. Music was rendered completely disharmonious although single tones sounded normal. There were no changes in vision, taste, smell, appetite, vital signs, or motor coordination." (Shulgin and Shulgin, 1997)

Because DiPT is completely unique in its ability to distort hearing, some researchers have been eager to examine its microbiological behavior to figure out what exactly can happen in somebody's brain to distort pitch. Thinking broadly, this could also inform the science of tone deafness, which causes about 5% of the population in the United States to misperceive pitch.

The chemical structure of DiPT (N, N-Diisopropyltryptamine)

Neurobiology of DiPT

All psychoactive drugs, which alter one's experience, work by acting as neurotransmitters in the brain. Neurotransmitters bind to receptors on neurons in the brain, triggering or repressing activity in that particular cell. For example, dopamine binds to dopamine receptors in the reward system in the brain, which stimulates activity in the brain cells there. Lets look at some common neurotransmitter receptors:

| Receptor Type | Role in Brain | Color in Figure |

|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | Regulates mood, appetite, sleep | Beige |

| Dopamine | Mood regulation, reward | Red |

| Adrenergic | Stimulation, alertness, arousal | Green |

| Histamine | Regulation of wakefulness, body temperature, and apetite | Yellow |

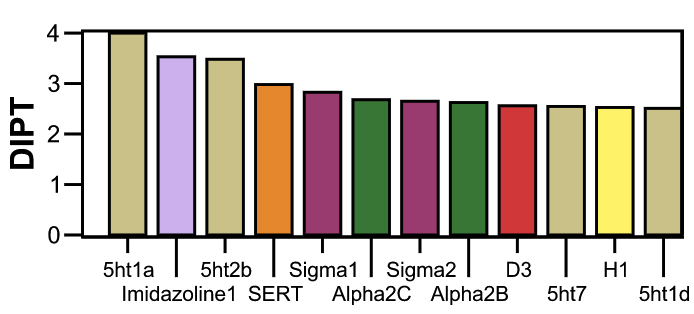

All classic hallucinogens (like LSD) work in part by stimulating similar receptors. However, each unique drug has a certain "receptor profile" that shows how different drugs binds to different receptors. Each drug's unique receptor profile is may help us understand why intoxication of different compounds can cause such different experiences. Let's look at the receptors that DiPT binds to, as determined by a study in 2010. If any of these receptors are unique to DiPT, perhaps we can discover a molecular explanation for this unique auditory phenomena!

The receptor profile for DiPT. The left axis indicates how likely DiPT

is to bind to that particular receptor. Refer to the table above for

color codes of common receptor types. From Ray, 2010.

After examining each of these receptors, in turns out that every single receptor DiPT binds to is also bound to by hallucinogens that are known to cause visual distortions, such as psilocin, LSD, and DOI. Unless DiPT engages receptors interactions that we are not accounting for (which is very possible), it is not obvious which molecular-level behaviors account for the auditory affects of DiPT. This is a common thing to find in science: a promising pursuit might not actually take you anywhere conclusive. My personal experience is that whenever I look to answer a particular hypothesis, I end up finding very few real answers, and a ton of new things to test.

Conclusion

When studying something as complicated as hallucinations, there are no easy answers, and many interesting questions. Animal research into DiPT has shown that rats are able to discriminate between DiPT and other hallucinogens, and mice under the influence of DiPT are less likely to learn to recognize tones, which may reflect that they experience pitch distortion.

The discovery of a compound DiPT teaches us that we in fact understand very little about the process of hearing in the brain, and gives us a tool to investigate. Future research directions could include continued microbiological research on receptors, neuroimaging to examine activity in different parts of a brain under the influence of DiPT, or continued animal research.

Sources

Arnie Battaglene. (2007). Sasha Shulgin in his lab.

Bennett, D. (2005, January 30). Dr. Ecstasy. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/30/magazine/dr-ecstasy.html

Carbonaro, T. M., Forster, M. J., & Gatch, M. B. (2013). Discriminative stimulus effects of N,N-diisopropyltryptamine. Psychopharmacology, 226(2), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2891-x

Hamlet, W. R. (2010). The effect of N, N-Diisopropyltryptamine on modified acoustic startle reflex tasks. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261322305_The_effect_of_NN-Diisopropyltryptamine_on_modified_acoustic_startle_reflex_tasks

Kalmus, H., & Fry, D. B. (1980). On tune deafness (dysmelodia): frequency, development, genetics and musical background. Annals of Human Genetics, 43(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1980.tb01571.x

Power, M. (2014, June 3). Alexander Shulgin. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/jun/03/alexander-shulgin

Ray, T. S. (2010). Psychedelics and the Human Receptorome. PLOS ONE, 5(2), e9019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009019

Shulgin, A., & Shulgin, A. (1997). Tihkal: The Continuation (First Edition edition). Berkeley: Transform Pr. Retrieved from https://www.erowid.org/library/books_online/tihkal/tihkal04.shtml

Shulgin, A. T., & Carter, M. F. (1980). N, N-Diisopropyltryptamine (DIPT) and 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (5-MeO-DIPT). Two orally active tryptamine analogs with CNS activity. Communications in Psychopharmacology, 4(5), 363–369. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/6949674

Related posts

- Steemit for Students – more about this post series

- How to Keep Track of Facts – tips for citing information

Thanks for reading!

Your post was a bit similar to breaking bad series..... Your post made me think about that... Keep steeming!!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks @sid9999! I guess there's an audience for content about "brilliant rogue drug chemist" types out there.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

a good drug to take before watching a chick flick with a girlfriend, it will sound hilarious and becomes fun.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Awesome. This guy reminds me of my former friend who was creating all kind of drugs in his underground lab. The real hypocrisy is though when the allowed him to do so and when he wanted to share his findings with the rest of the world instead of keeping the information just for himself he got stopped...

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yeah, it's an interesting ethical and legal quandary. Must have been very tense for both Shulgin and his friends at the DEA. I wonder how the personal relationships played out over that time period.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @somethingburger! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

brilliant - well written with some dense material. I tend to glaze over when I start to read about receptors and anything microbiology really, but you concisely presented a good biological puzzle.

I'm totally naive to drug biology, but this mystery makes me imagine that there's a whole other mediating level of drug effects... not what receptors they bind to, but how they enter the brain having an effect in and of itself, or how they disrupt other neurotransmitters.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit