You won’t find it in your family album, but a tiny prehistoric creature with a bag-like body, a huge mouth and no anus has become the best candidate yet for our earliest known ancestor.

Thought to have lived as long as 540 million years ago, the creature is the oldest known member of a large group of animals known as deuterostomes, which includes vertebrates – such as humans – as well as starfish, sea urchins and a host of other fauna.

While it is highly unlikely the new species is our direct ancestor, scientists say the creature could be very similar to it. As a result, the discovery of the fossils sheds light on the early stages of our evolution.

“In effect what we are suggesting here is that this is the earliest, oldest, most primitive of the deuterostomes,” said Simon Conway Morris, professor of palaeobiology at the University of Cambridge, and a co-author of the research. “This is, if you like, the starting point of an evolution which led ultimately to things as different as a sea urchin, starfish and rabbit.”

Discovered in sedimentary rock in Xixiang County in the Shaanxi province of central China, the species has been dubbed Saccorhytus coronarious for its sack-like, globular body and large mouth. Just one millimetre in length, the tiny animals are believed to have lived on the sea bed, where they would have nestled between grains of sand and moved by wriggling.

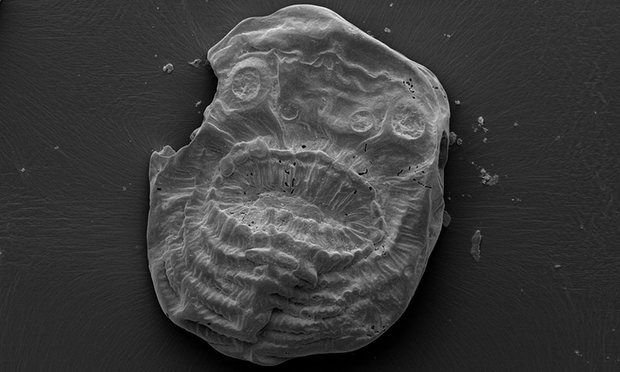

“When you look at them under the microscope they look like tiny grains of black rice, frankly – they are pretty uninteresting – but as soon as you put them under the electron microscope, the detail becomes absolutely phenomenal,” said Conway Morris who, with colleagues from China, has published the discovery in the journal Nature.

Among the details revealed by such techniques are a series of folds or wrinkles around the creature’s mouth which, the authors argue, could have allowed the animal’s mouth to dilate allowing it to swallow relatively large prey. Like humans, the creature has bilateral symmetry – that is, two symmetrical halves.

The large quantities of water the animal would have swallowed while feeding, adds Conway Morris, were likely ejected through a number of openings that can be seen on each side of the creature’s body. “These are, we suggest, the precursors of what we call the gill slits which you see in a fish,” he said. The role of small pores across the body, he adds, is more of a mystery, although he suggests that they might have been involved in securing the animal to sand grains, possible by releasing some sort of adhesive, or may otherwise have played a sensory role.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the animal appears to be lacking an anus. While Morris admits it is possible that the team simply haven’t spotted it, he points out that other creatures, such as the worm-like acoels, are also known to lack the orifice. “These things are so small, you can envisage something which is basically just a digestive sack with holes on the side,” he said of the new creatures.

Imran Rahman, museum research fellow at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and an expert in the field, described the findings as exciting.

“These are really interesting and to my mind surprising fossils,” he said. “[They have the] potential to greatly improve our understanding of the early evolution of deuterostomes, which is the major group to which vertebrates – including humans – belong, so they are obviously going to be important going forwards for understanding our evolutionary history.”

The tiny size of the fossils, he adds, is particularly remarkable, noting that previously discovered fossils of younger deuterostomes are often several centimetres in length. “That kind of opens up the tantalising prospect that maybe some of these oldest animals were really microscopic as well,” he said.

It’s a point, says Conway Morris, that could shed light on an enduring conundrum: why there is an apparent blank in the fossil record from around the time that animals are thought to have emerged based on the so-called “molecular clock” – an approach that estimates the dates of evolutionary splits from the rate at which genetic differences accumulate.

“If indeed the first of these animals including Saccorhytus were very, very tiny, they could only preserve in very, very exceptional circumstances – they basically slip through the fossilisation net,” said Conway Morris.

While Conway Morris admits the idea is speculative, the latest discovery, he says, makes it an intriguing possibility.

“The question here of course is: is it possible that there is a deep cryptic history that has almost entirely eluded discovery because these things are absolutely tiny?” he said.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jan/30/huge-mouth-and-no-anus-earliest-known-ancestor-saccorhytus-coronarious-evolution

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @vamius! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @vamius! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit