Kim Carsons, the “morbid teens of unwholesome proclivities” who stars in William S. Burroughs’s novel The area of dead Roads, would like Richard Barnett’s gorgeously illustrated new book, The sick Rose: disorder and the artwork of medical instance. In his father’s “good sized and eclectic library,” Kim discovers a trove of clinical texts, which he devours, driven by his “insatiable appetite for the extreme and sensational”:

He cherished to examine approximately illnesses, rolling and savoring the names on his tongue: tabes dorsalis, Friedreich’s ataxia, climactic buboes…and the photographs! the poisonous pinks and greens and yellows and purples of pores and skin sicknesses, instead like the items in those Catholic stores that sell shrines and madonnas and crucifixes and spiritual images. there has been one skin disorder in which the skin swells right into a red wheal and you could write on it. it'd be a laugh to find a boy with this disorder and draw pricks all over him. Kim idea perhaps he could observe medicinal drug and turn out to be a medical doctor, but whilst he preferred illnesses, he didn’t like unwell people.

As an established habitué of medical museums and, much less thankfully, an all-too-frequent visitor to the O.R. (short model: most cancers, publish-op complications), I recognise the types: the gourmet of the Pathological chic, due to the fact i am one, and the misanthropic physician who places the irony in “caregiver,” due to the fact I’ve met him inside the most cancers ward.

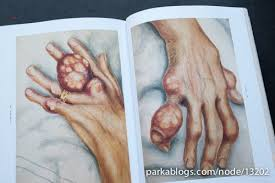

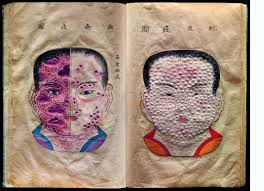

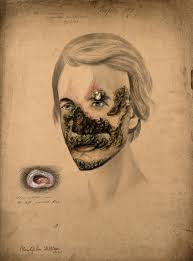

simply what is it that makes some of us no longer handiest now not preclude our eyes but fasten onto pictures just like the ones in Barnett’s book, antique clinical illustrations taken from the collections of the Wellcome Library in London? within the unwell Rose, Barnett—a professor at Pembroke college, Cambridge who became nicely on his way to a point in forensic pathology earlier than he veered off into the humanities—has curated a collection of normally 18th and 19th-century photographs of such grotesque beauty or revolting grossness they make the thoughts gasp. here is a delicately, almost tenderly rendered cartoon of a nude younger woman with ichthyosis, her head discreetly cropped off, her girlish frame disfigured with the aid of Rorschach-like blots. right here, on the e book’s cowl, is an unforgettable portrait of a younger Viennese woman depicting her an hour after she reduced in size cholera—and an insignificant 4 hours before she died from it. There’s a peculiar aesthetic jolt, almost a ghastly beauty, to her glaucous skin and blue lips, the ironic comparison between her demure braided hairstyle and the excessive-opera melodrama of her horrified expression. here is an old man with leprosy, his face a mass of crusted growths that look uncannily like crumbling rock, which makes you think of The element from The tremendous four, then makes you experience cheap and ugly for doing so, because there was a person in there, behind the ugly masks the sickness made him put on, under the pain the ailment—and the people who shrank from his touch—made him experience. here, too, is a girl with dermatographic urticaria, the skin condition Kim dreamed of setting to a laugh use; actual to Kim’s fantasies, a person—a health practitioner?—has used a needle or a pencil to write down on her pores and skin, causing the words to stand out in welts, like the writing on the possessed girl’s belly within the Exorcist.

Barnett is a cautious, erudite historian of technological know-how, no longer to mention a fantastic stylist who turns a pleasing word, but what makes The unwell Rose so affecting is his refusal to disclaim the perverse pleasures of these items—the “severe and sensational” fabric that captivates the Kim Carsons in a number of us—whilst on the same time forcing us to confront the politics of looking; the psychological and philosophical fees of savoring the ache of others, pain that reverberates down through the centuries in pix that once seen, can’t be unseen.

Mark Dery: I do not forget the younger Richard Barnett because the form of little one who might stare, in undisguised fascination, at some abject sufferer with an giant goiter, and who grew into the form of teenaged boy who stored under his bed, in area of the same antique Playboy, a colour atlas of pathological anatomy. Am I incorrect?

Richard Barnett: pretty wrong. i used to be an particularly shy and introverted little one (probably it’s extra accurate to say a commonly shy and introverted English little one), with a satisfactory horror of deformity, violence, and viscera. Skulls mainly, for a few purpose: I remember being fully spooked for a few weeks by using the usage of the sight of a sheep’s skull we decided out on a walk even as i was possibly seven or eight. (i wonder if I’d caught sight of a Dennis Wheatley paperback someplace in advance?) The bareness of the tooth, the emptiness of the attention-sockets, the texture of some issue ghastly lurking beneath the floor of life—as Eliot says, “the cranium below the pores and pores and skin.” So there was a kind of fascination, sincerely, but it became a few element I may want to only undergo to glimpse out of the corner of my eye, some issue I couldn’t confront at once till i was tons older. i was a ways happier hidden away with The e-book of one thousand Poems.

M.D.: searching once more, modified into there any incident or ongoing obsession, to your young people, that now appears premonitory of the pastimes that flowered inside the sick Rose?

M.D.: some. One pretty out of my manipulate: all through my lifestyles I’ve had pretty a piece of surgery, commonly an operation every six or seven years or so. (I’m now not significantly ill, thank heavens; just no longer thoroughly put together.) As a boy this, quite obviously, scared the hell out of me: the pain, of course, but likely greater the enjoy of losing manipulate over one’s frame, of being naked and prone below the gaze of impassive strangers, and the feeling of being deserted to at least one’s surgical destiny by means of one’s dad and mom, helpless as they're in that situation.

As an grownup I’ve come to enjoy very tremendous: going beneath with a brand new anesthetic is one of the exquisite metaphysical studies, and one I assume everyone need to enjoy as soon as. some other become studying, on the age of eight or nine, Keith Simpson’s forty Years of murder. Simpson become one of the main British forensic pathologists (I think you name them medical experts) in the mid-20th century, and studying his autobiography set me on my early career route to medical college. Oddly sufficient it wasn’t the gory aspects of his artwork that interested me, but as an alternative the narrative, nearly progressive component: the reconstruction of a tale, a scene, probably an identification, from scattered and fragmentary clues, precisely what I now do as a historian.

M.D.: in your introduction, you speak about the cognitive dissonance inspired by the usage of antique medical instance. searching at this stuff crosses our indicators; our intellects say aesthetic rapture, our emotions say visceral horror. A good deal of it's far exquisitely rendered, with apparent artistic cause; in lots of those illustrations, the classy eye and the clinical gaze share equal billing. on the identical time, plenty of the subject rely is quite grisly stuff: dissections, disfiguring pores and pores and skin illnesses, the ravages of cancer, ulcerations due to typhoid, the earlier wizened face of an infant bothered with the aid of hereditary syphilis.

To what volume do you revel in the ones forms of conflicted emotions, whilst looking at clinical illustrations much like the ones you’ve collected within the sick Rose? How massive a part of the inducement in the back of the ebook end up the selection to make feel of the uncanny electricity of those pix; to parse the emotions they evoke?

R.B.: I think some component could be incorrect if those illustrations did not evoke emotions of struggle and unheimlichkeitin us. one of the most difficult, and at the identical time maximum worthwhile, ways to have interaction with those pictures is to enjoy and mirror on the sorts of energy they own: sympathy, disgust, beauty, image-realism, dignity, pity. i am able to’t do better right here than to copy what I wrote within the advent: “[These images] deliver us, so to talk, the outside of the inner; they're insistently concerned with surfaces, but surfaces that during lifestyles and fitness are never visible … They gift an uncanny spectacle of the useless frame articulated: now not most effective prepared and installed for display, however also made to talk (in a voice that isn't always absolutely its personal).” There’s a peculiar and intimate form of sublimity about them; they undermine the seeming integrity of the viewer’s own frame with the aid of foreshadowing its last destruction via ailment, damage and death.

As I wrote the book, and spent increasingly time with these depictions of struggling and disfigurement, i discovered myself turning into uneasy in ways I couldn’t pin down. It wasn’t until the ebook changed into completed that I could placed this into phrases, in an essay for the Wellcome Library weblog. without repeating too much of that here, i found myself asking whether those images in reality constitute a shape of human stays. And that makes me want to be very, very cautious about what I do with them.

M.D.: having said that, you well known that the anatomical and pathological textbooks and atlases created among the French Revolution and world warfare I—the “golden age of clinical picture-making,” on your estimation—represent “a corpus of artwork that is lovely and morbid, singular and sublime.” Reflecting on the cultured seductiveness and visceral repulsion of antique medical illustrations, you ask, “How ought to we apprehend this tension between ‘the beauty of the coats of the belly’ and ‘the sight of a useless and mangled frame’? must we searching for to solve…it, or ought to we exercise what…the medical student-grew to become-poet John Keats known as terrible capability—the capacity to be ‘in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable attaining after fact and reason’?”

within the unwell Rose, you depart the query hanging within the air. I’d be curious to hear you enlarge on it, if not clear up it.

To top the pump, I’ll say that I’ve usually felt that the enchantment (to a number of us, at least!) of, say, wax moulages of diseases or deformities, or the 19th-century chinese painter Lam Qua’s photos of patients with gruesome tumors, owes something to our tendency, after Surrealism, to peer such things as desires made flesh. also, the emotional and intellectual impact of this form of factor is synonymous, in my thoughts, with the tug-of-warfare between wonder and terror that the 18th-century logician Edmund Burke calls the chic. In reality, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., in a brief, unsigned overview of an exhibition of Lam Qua’s paintings (“Illustrations of Tumors some of the chinese,” Boston clinical and Surgical journal, might also 21, 1845), calls Qua’s visions of “tremendous diseased growths” an instance of “the pathological sublime.”

R.B.: nicely, it’s very Keatsian to go away the question striking, and my very own view is exactly that we have to. I’d hate to clear up this tension, because it’s so captivating, so idea-upsetting. It’s now not that I assume those photographs must provoke a sure set of reactions, however alternatively that we should technique them in a manner that recognizes the power they have got, and the roots of this power in our private fragile human condition. An earlier technology spoke back to this electricity by way of manner of locking the ones photos away (literally in a few cases), and the cutting-edge technology responds, in so many instances, with the aid of reframing those photos as lack of life kitsch or gross porn. every attitudes, of route, replicate moving cultural conditions, but both strike me as deeply inadequate. They live clean of the critical query of strength, and neither enables to attract out the richness and intensity those images embody (a word i found myself using an extended way too regularly in successive drafts of the e-book) and the complexity of the responses they initiate.

speakme of which: you’re clearly right close to Surrealism. The uncanniness of those pictures is living within the truth that, like Dali and Magritte (and, of course, Bosch earlier than them), they use the strategies and spaces of realist art work to depict matters that appear perverse, nightmarish, unreal.

M.D.: In a feel, Surrealism became born within the O.R. (or, in case you need, the dissecting desk): André Breton, the movement’s founder, studied medication. The Surrealists drew thought from Lautréamont’s Maldoror, a bizarre, hallucinatory nineteenth-century novel whose terrific-recognized line, “lovable because the threat meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing system and an umbrella,” have grow to be a Surrealist slogan. The Surrealist mechanism, par excellence, for forcing dreamlike unfastened-affiliation modified right into a parlor endeavor called “the super corpse,” which concerned creating Frankenstein-ian mash-u.s.a.of drawings or poetry. The Surrealist movie Un Chien Andalou, through Dali and Luis Buñuel, opens with a razor slicing into an eye with clinical dispassion. And, of path, Surrealism’s crucial motive was to peel again our aware defenses, exposing the innards of ourselves—to anatomize the unconscious.

extra recently, iconoclastic novelists together with William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard have drawn notion each from Surrealism (the college technique, “determined” literature) and remedy: Burroughs, who briefly studied medication, cut up and sutured texts collectively; one in all his amazing-recognized literary modify egos is the drug-addled, hilariously depraved Dr. Benway. Ballard studied medication at King’s university, with the intent of turning into a psychiatrist, and spoke regularly about the effect of medical imagery, mainly the enjoy of anatomizing a cadaver, on his literary imagination.

What do you're making of the plain connection, right here, among the novel inventive creativeness and remedy as transgression, directing our hobby to disease, internal organs, and different elements of the body society would possibly as a substitute now not study?

R.B.: The awesome Dr. Benway has been in my thoughts a remarkable deal over the past decade, as I dropped out of scientific faculty, and searched for a frame wherein to location my very very own questions about remedy and its electricity, and underwent greater surgical treatment, and tried to start wondering with my complete frame in choice to just my brain. The flesh, and greater in particular a feel of rage and frustration at its limitations, is the clue with which we are so frequently compelled to begin our investigations, clinical and literary. For me, the telling time period is post-mortem, from a Greek root which means to peer for oneself, but additionally, sincerely, to peer oneself. The body inside the library is typically our personal, and it’s no coincidence that lifestyle and artwork are suffused with corporeal metaphors. “O, that this too too strong flesh would melt, thaw, and solve itself right into a dew,” and so forth on your examples. One have to write a whole thesis for your query, however it appears to me that the hidden link right right here is the libelous, barbarous, interesting statement that a person or women is multiple hundred pounds of meat gifted with the troubling electricity to stroll and talk and realise something of itself.

M.D.:inside the ebook, you ask, “What aesthetic and cultural values have been inscribed in those pics, and via whom?” It’s easy to come across social Darwinist ideas approximately race in Victorian clinical imagery or the Romantic aesthetic in nineteenth-century depictions of tuberculosis sufferers. We applaud ourselves for questioning the purportedly “goal clinical gaze,” as you call it, of pre-cutting-edge-day clinical imagery.

thru evaluation, it’s difficult to figure the cultural biases, ideological subtexts, and aesthetic affects within the scientific imagery of our 2nd, introduced to us thru X-rays, CAT and puppy scans, MRIs, ultrasound, and so on. Is that due to the reality such device-made photos truely are more representationally true, less prone to cultural and historical assumptions, than photographs created by using the human hand? Or are we as blind to their aesthetic and ideological biases as, say, the Victorians have been to the clinical imagery in their day?

R.B.: that is a tough one. As you're pronouncing, we will be predisposed to treat the generation of “mechanical objectivity” as sincerely better, more neutral, extra true. however as a cultural historian I’m professionally suspicious of any sweeping claims to more neutrality or objectivity. I’d say the most vital aspect to undergo in mind about any kind of instance of the human body is that it is a illustration and not the element itself.

X-rays, as an instance, are pretty lots the most massive shape of mechanical objectivity in present day remedy; they’re primarily based on a technology—pictures–which has been in commonplace use for more than a century, and they certainly don’t seem like an obvious instantiation of cultural values. however have you ever ever tried to interpret a simple popular chest X-ray? It’s an art work. It calls for a honed, skilled gaze that may’t (as a minimum hasn’t but) been decreased to a hard and fast of algorithms. It suggests a few matters, mainly bones, in crisp detail, and others– smooth tissues–in hazy, indistinct define. It’s like anatomizing a cloud, or a ghost. The human element, the cultural and aesthetic and person element, stays gift and essential.

Objectivity in technological know-how is continually and everywhere a communal business organisation, a rely of debating and agreeing on shared standards of rigor and interpretation, and imposing the ones necessities in the community of practitioners. So despite the truth that it can be extra difficult to look aesthetic and ideological undercurrents in those technology, I anticipate we are able to see them in the moving styles and meanings of objectivity over the past couple of centuries. The grand claims made with reference to fMRI studies of the mind are a terrific instance of this. but don’t get me began out on neuromania, cultural, medical and academic, or we’ll be right right here till Christmas.

M.D.:You communicate approximately the politics of “concerning the ache of others,” as Sontag positioned it—the dangers of commodifying or even actually emotionally exploiting, for prurient purposes, photos of ailment, disfigurement, death. You wonder if such photographs “certainly represent a form of human stays,” and urge us to think twice approximately the politics of searching, and to be “very, very cautious” what we do with the ones pictures of various peoples’ pain.

In that mild, i am capable of’t help questioning what you remember the burgeoning hobby, amongst erudite weirdoes and hipsters of the morbid persuasion, in the greater obscure and curious corners of scientific history. I’m thinking of the subcultural demographic inquisitive about the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn, the reality-tv show Oddities, the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, and of course books like yours. (ought to we mention Gunther von Hagens’s frame Worlds exhibitions of “plastinated” cadavers? Arguably, they represent a crass, mass-market model of this visitors in “darkish” clinical imagery, reviving the general public anatomy instructions of 17th-century Bologna for the age of Miley Cyrus and anal bleaching. And wherein does the fad for taxidermy fit into this phenomenon, if it does?) This emerging hobby expresses itself at the whole through the consumption of images.

R.B.: Tempting as it is to take an intensive left emerge as the horrific dialectics of anal bleaching, I’ll say, first, that it’s absolutely no longer my vicinity to inform all of us how they have to respond to those pictures. Of direction I’ll say to each person who’ll concentrate that we should deal with them with dignity, that we need to make an effort to understand the wealthy and complicated topics they embody. I’m quite adverse to individuals who clutch clinical or ancient images out of context and scatter them throughout Twitter or Pinterest and now not using a cause past lurid gawping.

but unwell elegant has many faces, and that i discover such things as Morbid Anatomy and Oddities very well heartening. (full disclosure: i was scholar in residence on the Morbid Anatomy Library in April 2014; whilst i was there I were given to apprehend Evan Michelson and Mike Zohn of Oddities, and that i’m now an honorary founding member of the Morbid Anatomy Museum.) Morbid Anatomy mainly has pioneered a manner of commencing those kinds of collections as lots as clever, curious, unorthodox oldsters outside the traditional confines of an academic museum or library, and prolonged may it prosper. and that i’m sympathetic to von Hagens, weird character although he may be. Plastination is streets in advance of formalin as a way for retaining anatomical specimens, with considerable capability as a coaching device in scientific colleges. It appears to me that what unites von Hagens and William Burroughs (aside from a taste for natty headgear) and all of the human beings we’ve mentioned right here is an obsession with the antique philosophical imperative: nosce te ipsum, “understand thyself.”