When a woman first senses and responds to the spirit of her unborn child, this is known as a “quickening.” When the spirit of an age changes, the mystic, the poet and the artist sense this shift in global consciousness. If this quickening ushers in darkening times, the world relies upon these keepers of culture to work with the dying light to reflect not only what is being lost, but what can be birthed and shaped into alternate possible realities.

Each day seems to offer a fresh serving of bloodshed, hatred and intolerance, calling the artist, the mystic and the poet to respond. Opening today in Los Angeles is one such response: “Satan’s Disco,” a group exhibition of contemporary art whose “artists are not afraid to shine a light into the shadows …” (Art Share-LA)

Contributing to this show is Monsù Plin (PLIN), one of TTDOG’s most often referenced artists. PLIN draws from traditional fine art, folk art, indigenous art, graphic art, street art and graffiti to create expressive and communicative works that directly engage the viewer. In his collection of works for “Satan’s Disco,” he has brought together and integrated aspects of each of these influences. TTDOG caught up with PLIN by email for a Q&A about his collection.

TTDOG: What inspired this collection and how does it fit in with the brief of “Satan’s Disco?”

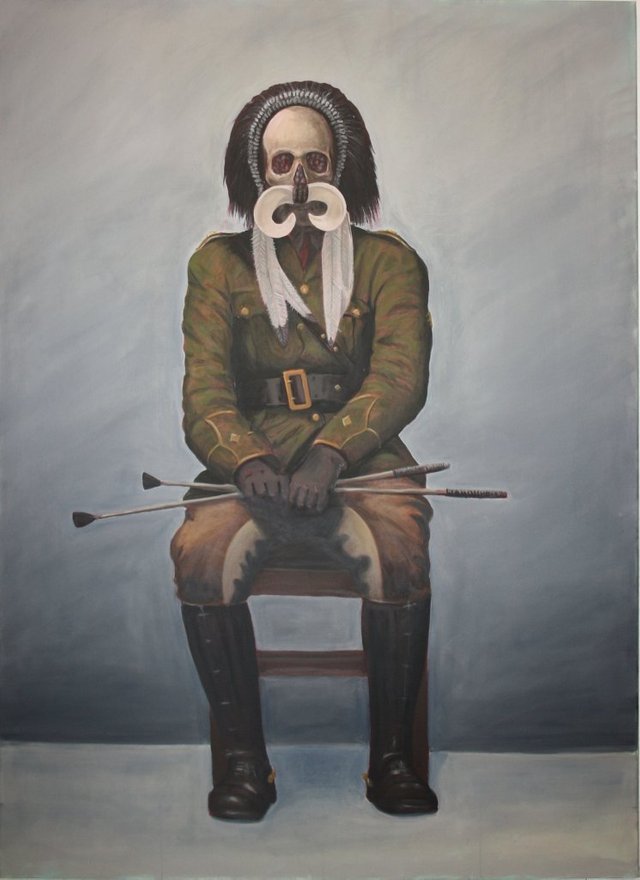

PLIN: It all started with a visit to the De Young Museum in San Fransisco about 4 years ago when a Papuan ancestry skull caught my eye on the way out. It was the skull of an Asmat ancestor beautifully decorated with beads, shells, feathers and warthogs tusks. I have always been intrigued by masks and something about it immediately entranced me. I knew I needed to incorporate it into my work. When I returned to LA, I overlaid it on a 19th century cavalry portrait and the collection was born.

Although the collection can be interpreted many different ways I believe that it forces the viewer to confront the messy and often ugly history of imperialism and the expansion of western culture. I see this as illuminating a dark corner of my own cultural heritage that is far too often ignored although it is shared by most of the world in some way or another.

TTDOG: In revisiting a 2013 theme that you began with Seated Figure 1, what has evolved for you, in the intervening time?

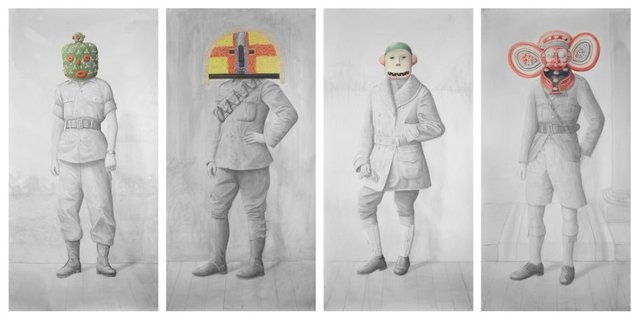

PLIN: Over this time I have been working on a body of oil paintings and the collection for Satan’s Disco all of which share the same theme. Although in the past 3 years I feel that I have grown as an artist and my work has developed in depth and sophistication, I believe that the most significant changes have occurred in the world around us rather than in myself or my work. Today, as we are experiencing the repercussions of industrialization and globalization, issues regarding cultural identity, compatibility, appropriation, and domination have become much more acute and poignant. Because of this, the body of work has become more relevant and enters into an important discussion in which we have to reassess how we interpret culture in a new global era.

TTDOG: Tell us about your choice of the particular branches of military/military rank and the masks worn by the figures? What appeals to you about these combinations and about the particular associations or cultural references these may conjure for the viewer?

PLIN: I tried not to get too specific in my military references in an effort to allow the viewer to explore his or her own ideas on what they represent. I selected the ranks and uniforms more to give the collection a bit of diversity in its representation of cultures and climates. In contrast with the mask, differences between the bodies are minimal, even superficial. Their utilitarian quest for uniformity have made them homogenized and faceless much like our modern, globalized culture today.

TTDOG: Your pieces reference 19th and early 20th century, empire-era, military portraits. Why has this period and type of portraiture captured your imagination and what concepts has it allowed you to play with, in this collection?

PLIN: I think the turn of the century captivates me for many reasons. It was an incredible transitionary period for the world, much like what we are experiencing today. Besides the obvious reference or western imperialism, I am also interested in the many ambiguities the photographic portraits represented. This transition from the traditional to the modern manifests itself both in the uniforms and representation of military power but also in the early use of photography influenced by the transition from painting. Not only do they capture the death of an ancient agricultural society, but also the death of painting and traditional art of the time.

TTDOG: What is your relationship with various forms of power and the exercise of that power? In what ways did that relationship impact and find its expression in this collection?

PLIN: Power is a concept that is difficult to grasp as it is often elusive and opaque. I think I have always exercised a healthy suspicion for power structures, a habit I owe largely to my experience with graffiti. However I am also becoming aware of the unwitting role I play (as we all do) in reinforcing these structures which leads me to seek out forms of empowerment, such as art making.

The figures represent these authoritarian power structures we are all familiar with and, in the context of my experience, the masks can be compared to those colorful bursts of graffiti decorating the grey walls of an oppressive urban landscape. Just like in graffiti, there is a certain amount of struggle over the idea of ownership, both in physical and creative property. My collection examines ideas of a dominant culture appropriating often sacred cultural features of indigenous communities, but ignoring the rest. This non-consensual cultural theft permeates the modern psyche which is especially visible in the progression of modern and contemporary art. Although the masks are somewhat dominated by their unforgiving military bodies it is important to note that if you neglect the head, the body is rendered useless, just as isolating a mask from the cultural context in which it was created dismisses its very significance.

TTDOG: You contrast head and body. From a holistic point of point of view, there is also the heart and the spirit. The kinds of masks you incorporate in your visual language are associated with the endowment of spiritual powers. What, if anything, has been your journey to work with the spiritual meaning and power of these masks?

PLIN: Although I am not religious in the traditional western sense, I feel much more of an affinity to the types of spirituality often practiced by indigenous cultures around the world. To me, the two are distinctly different in that traditional organized religions tend to look inward at the human spirit while other, often indigenous, spiritual practices address the interaction between humans and their environment. Another distinction which is present in my work is the idea of hierarchy which is fundamental to our western psyche and determines the way we structure our society and approach our spirituality. In Western religions, we are inclined to anthropomorphize omnipotent deities, whereas non-Abrahamic spirituality tends to look to spirits who reflect the patterns of nature rooted in our experience on earth. Considering the fundamental differences between these strains of spirituality and religious practice, I am drawn to their visual representation and the differences between indigenous abstraction and the realism of human-based depiction in western tradition.

TTDOG: On a more practical level, why have you chosen to use this format and media for this collection that is being exhibited in “Satan’s Disco?” What challenges did you face in executing the pieces?

PLIN: I decided to go for the large format because I wanted the viewer to relate in a direct way with the subject matter. Since I had chosen to essentially personify cultural relationships, it seemed only natural to make them at a human scale.

As is our practice, we had one final question for PLIN: For what are you most grateful and where do you find your greatest joy?

Hi! I am a content-detection robot. This post is to help manual curators; I have NOT flagged you.

Here is similar content:

http://tenthousanddaysofgratitude.com/index.php/2016/07/27/monsu-plin-illuminating-the-dark-corners-of-cultural-history/

NOTE: I cannot tell if you are the author, so ensure you have proper verification in your post (or in a reply to me), for humans to check!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This entire post is plagiarized. Please delete it. I am the author and editor of tenthousanddaysofgratitude.com and I did not give permission for its use. I ask that you delete not only the post but ban @benjiberigan and @tessadavis for downvoting and hiding what amounts to copyright infringement.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

just gave you an upvote. I am sorry

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Photos in this piece are also copyrighted by photographers and not Benji Berigan. Photo of Monsu Plin on train is copyright Artem Barinov. Photo of Monsu Plin at work is copyright Cyndy Fike. Photo of Monsu Plin with Mayan ruins is copyright Francesca Perruccio. All other images are copyright Monsu Plin.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I, Tania D Campbell, am the author of this content, originally published on TenThousandDaysofGratitude.com (TTDOG in the article). This post was copied verbatim without permission or attribution to the author/publisher of the content or attribution to the photographers of the images that appear here on Steemit or on republishing sites that take their content from Steemit. I requested this post be taken down from Steemit but it cannot be removed, once in the blockchain, and despite being downvoted here, it has been republished elsewhere on the net. As the next best remediation, Benji Berigan issued a public apology for publishing this without permission and I'm posting it here, so that it accompanies all republications elsewhere on the net. This content does not belong under the byline of Benji Berigan but was written by me, Tania D Campbell. Berigan's public apology can be read here: https://steemit.com/steemit/@benjiberigan/a-public-apology-for-posting-without-attribution-monsu-plin-illuminating-the-dark-corners-of-cultural-history

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit