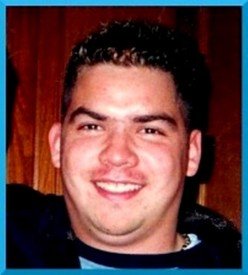

This story is about my son, John. He died at the age of 28 after a three- to four-year-long addiction to Vicodin that I didn’t even notice he had, even though he lived with me during that time. He was a very high-functioning addict.John’s teenage years were very trying, as he was drinking and smoking pot almost every day. Calls from the police in the middle of the night were becoming common. And yet, he looked like the proverbial boy next door. He was an outstanding athlete, with many trophies and awards. He played baseball and was a pitcher, and this was the brightest shining star in his life. He was also very gifted intellectually and artistically. At some point in his early 20s he toned down his drinking, as he got a promotion and he worked incredibly long hours. But he had a serious fall at work that injured his back. He was prescribed Vicodin and went for his physical therapy regularly. I was very concerned about John taking Vicodin, and when his therapy was over I asked him if he had stopped the Vicodin. As an addict often does, he lied and told me he wasn't taking it anymore. John still had that sense of invincibility that so many young people have.About two weeks before John died, he started becoming ill. He couldn't go in to work, which was unusual because he never missed a day. He couldn't keep any food down, and he couldn't even read or write anymore, which I discovered from his boss, who was also very concerned. John's addiction was now affecting every part of his life. I didn't know about his addiction at this time, but I did notice he started isolating himself, did not visit his family, quit baseball, and stopped going out with his friends. One morning John pounded on my bedroom door doubled over in pain and begged me to take him to the hospital. He was diagnosed with pancreatitis, but lied to the doctor about his drug use. When I went home to get some things for him, I found literally hundreds of empty little pill baggies stashed all over in his room. I also found what he titled his "Drug Schedule." He was taking 30 to 40 pills a day, and it was eating up his whole paycheck, which finally explained why he asked to move back home. On October 4, 2008, John went into cardiac arrest while he was still in the hospital—the day before he was scheduled to be discharged. This led to his being put on life support, which is a shocking thing to see, and prepped to be airlifted to the University of Michigan hospital for a liver transplant because his liver was failing. The doctors worked on him for a long time, but he never came back.As his mom, the visions of that morning are still so very vivid and heartbreaking. I was waiting outside John's door and a Code Blue was announced. A feeling of hysteria and fear started rapidly building in me. All kinds of people were running down the hall with various medical devices. The nurses had to keep pulling me out of the room, but I saw a person on John's bed giving him chest compressions. I saw the electric paddles. Eventually I sat down as reality set in. John was not going to make it to U of M’s hospital. John was not going to make it all. His life was over. When I saw John afterward, I just sat by his bed, astonished by the coldness of his body. All I could say to him was, "Why?" It was surreal, and I think I blocked it out for a while.The medical examiner who performed John's autopsy said that John was a 'dead man walking.' The acetaminophen in the massive amount of Vicodin he was taking damaged every single one of his vital organs. He never stood a chance.I am committed to educating young people about the incredible danger of addictive prescription drugs. Just because a doctor prescribed it does not mean it is safe. Opiate pain killers in particular are the most addictive prescription drugs and are so easy to obtain and hide. I would like to tell young people to not even think about it—and if they find that they do become addicted and cannot stop using, to please, please ask for help. There is a great deal of shame for someone with an addiction, but I believe they would be surprised at the immense help they would get. The people who have negative attitudes regarding addiction are becoming fewer all of the time. Addiction is a medical illness and it needs to be treated as such. John was an incredibly loved young man. Friends flew across the country to be at his funeral, and the incredible sadness about how his death could have been prevented just permeated the air. John was just coming into his own, but because he falsely believed he could handle abusing drugs, and because of the embarrassment he felt, he never asked for help. John was a very bright young man, and he knew when he reached that point of having a serious problem. But he never asked for help because his drug—the very thing killing him—had complete control over his life. For parents, losing their child for a reason that could have been prevented is so incredibly painful.All I have of John are memories, and of course his baseball glove and a few other things. But at the cemetery you cannot hold a grave marker. What I miss most about my son is his affectionate nature, his great sense of humor, and even the small things like hearing his feet bouncing up and down the stairs, the smell of his cologne—just everything about him.For parents, this is their greatest fear come true, because the grieving never stops when it is your child that has been lost too soon. Children are supposed to bury their parents. Parents are NOT supposed to bury their children.I took the Medicine Abuse Project pledge to help young people realize the very real danger of prescription drug abuse. To the kids reading this story, you are loved and have so much to give to the world. The temptation to abuse prescription drugs is very real, but the courage to resist that temptation is also very real.If my son's story saves even one life, then his life and death were not in vain.

DISCLAIMER: This is not my post. I'm trying to tell people about these stories. The link is right here: http://medicineabuseproject.org/stories/nobody-knew-how-bad-johns-addiction-was-until-it-was-too-late