When I was a child my father was a tower of strength to me, his body was gnarled but strong, like a giant oak tree.

When he was cut down, my world shook. - Antaeus

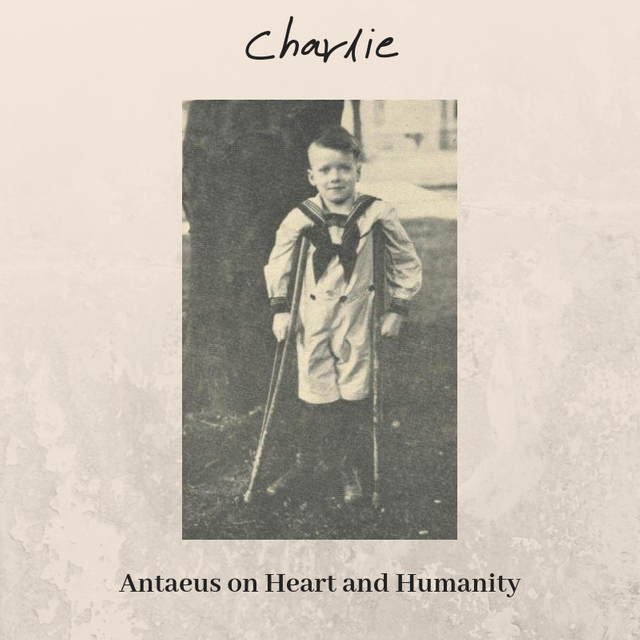

Charlie was born in Italy in the year 1915. He was the third youngest of two sisters and nine brothers. At the age of six months, he was stricken with Infantile Paralysis (Polio). The disease left Charlie with one leg shorter and weaker than the other, and he spent the better part of his childhood on crutches.

In 1928 Charlie's mother, Norma, immigrated to the United States with six of her children. They were to join Norma's five older siblings who were already living in the US. The olive-skinned, curly-haired, Sicilian boy arrived at Ellis Island commonly known as the "Island of Tears," on his 13th birthday. Once in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), a doctor conducted a "six-second physical" and denied Charlie entry into the United States.

Back then there were two main reasons why an immigrant could legally be denied entry: if a doctor diagnosed that the immigrant had a contagious disease, or if a legal inspector thought the immigrant was likely to become a public charge or an illegal contract laborer. In the reason for denial section on Charlie's paperwork, the doctor had written "Cripple."

A Congressman from New York happened to be on the island meeting his relatives. When he saw Norma crying, he intervened and demanded that the physician allow Charlie to enter the country with his family.

Life in the United States was easier on the young boy than his life on a farm in Italy had been, and he flourished. His arms grew thick and brawny from supporting himself on crutches. By the time Charlie had reached his twenties, he had tenaciously taught himself to walk without crutches, albeit with a pronounced limp and a painful back.

I can't speak to what Charlie went through when he was younger, as I wasn't born yet. What I do remember is that, as I was growing up, his crooked nose and scarred chin spoke volumes to me. Most of his life this gutsy man was referred to as "The Cripple" by the people in our inner-city area of Jersey City, New Jersey. Never to his face, though. To say that to Charlie's face would cost that person a tooth or two. I know because I saw him knock a molar from a troublemaker's mouth with one punch.

#

My father worked as a bartender and cook in a bar that was owned by three of his brothers. Standing on his feet preparing food and serving drinks for twelve hours a day was not an easy job. Especially for someone physically challenged.

The eight of us, my parents, my sister, four brothers, and myself, lived on the third floor in a three-room cold-water walkup. My dad would be up at 5:00 AM, six out of seven days a week to start his workday. Sometimes I would lie awake in the fold-out bed I shared with three of my brothers and listen to my father eat his breakfast of coffee and stale Italian bread.

Whatever the weather, rain, snow, or sun, and no matter how he felt, healthy, sick, or feverish, my dad went to work. There were no "sick days" or "sick pay" in those days. His "vacation" was the five days which included Christmas day when the bar closed for maintenance. My father didn't receive a paycheck for that week, so our meals were minimal because of it.

#

Monday to Friday were 12-hour workdays, Saturday was a 10-hour day, and Sunday was a 5-hour day for my dad. Most of those laborious 75 hours would be spent limping from one end of the 30-foot long bar to the other end, serving drinks and food.

From the age of seven until I was sixteen-years-old, I worked at that bar to help my father. I would show up at the bar at six-thirty in the morning to clean up the vomit and other messes in the men's room from the night before. After doing that, I would put all of the bar stools on top of the bar, sweep the floor, and mop up drink spills and more vomit. Then I would take the empty beer bottles down to the basement and bring up the full ones, along with the ice. I say this not to brag, but to make a point. These were all things that my father's brothers expected him to do before the bar opened for business, things that hurt his back and bad leg as he struggled to climb up and down the cellar stairs.

I never received payment for doing the work that I did. I did it so my dad wouldn't have to; because that's what family does. At least our family did. My uncles were a different story; they worked their brother like a dog.

My father was expected to do all of the work I just described, as well as tend bar and cook, for a small salary of $60.00 a week. Even for the 1950's, that was a paltry wage. In contrast to Charlie's 75-hour workweek, his brothers worked 35-hours a week, never went near the kitchen, and paid themselves very well.

After school, and on weekends, I would walk to the bar, where I would help out wherever I could. While my friends played stickball and other games, I worked. There were always dishes to wash, floors to sweep, and sundry other tasks that needed doing at the bar.

Every day, before I left the bar, my dad would embrace me and remind me that he wanted me to do better in life than he had. Every day I promised him that he would. My uncles, on the other hand, wanted me to take my father's place when he could no longer work.

#

I was eight years old when he saw my father bow his head and back away from a fight for the first and only time in my life. It was the summer of 1953. I was sitting by the open back door with my friend waiting for my dad to get off work. My father was waiting for his brother, Orlando, to relieve him at the bar. It was 8:30 in the evening, two and a half hours after quitting time, and my uncle hadn't shown up yet.

That particular day, the bar was unusually busy, and my friend and I watched as my dad's limp became more pronounced as the hours dragged on. Orlando was typically late by a half hour or more most days, and his tardiness usually went unchallenged. However, after working almost fifteen hours straight, two of them without pay, my father had enough. I could tell by the look on his face that he was hurting.

When Orlando finally arrived, the two men stood facing each other. My father told his brother never to be that late again. Orlando's response was deliberately insulting and demeaning. I still remember his words all these years later. "I own this place," he shouted. "I'll come and go as I please. You're lucky I don't fire you, nobody wants to hire a cripple." Then he turned to the crowded bar and yelled, "Isn't that right? Would any of you hire a cripple?"

"I would!" The words just shot out of my mouth into the dead silence of the room.

I saw my dad ball his fist, and although Orlando was three inches taller and several years younger, I figured he was toast. Instead of hitting his brother, Charlie just relaxed his hand, hung his head, turned, and limped painfully away. Most of the people in the bar just went on drinking. I could see how much those words hurt my father, so I shed the tears my dad wouldn't.

#

When we got home, I asked my dad why he didn't break his brother's jaw for saying what he did. My father patted his good knee, and I sat on it.

"I have six young mouths to feed and eight bellies to fill," he said. "If I hit Orlando, I would be out of a job, and there aren't that many jobs around for people like me. You'll understand when you have your own family."

I told my father I hated my uncle, and when I got bigger and stronger, I was going to beat up Orlando for him. My dad didn't do it often, but when he smiled, all signs of the pain he suffered every day disappeared. He smiled and kissed me on the forehead. Then he looked into his my eyes and said the words that I have passed on to my children. "We are all born with a demon inside us, and that beast feeds on hate. The more you hate, the bigger the creature gets. When the monster gets big enough, it will consume you too."

Those were pretty scary words for an eight-year-old. I was sure I could feel the demon eating away at my insides and told my dad as much. My father said I was just hungry, and he was right. As soon as we had our supper of rice and milk, the demon went away.

#

There were times, as a child, that I deliberately fed that monster. There wasn't a lot of money for food or clothing, so we were skinny, shabbily-dressed kids back then. Most of the clothes that I and my brothers and his sister wore were hand-me-downs from our older cousins. When we walked down the street, some of the other kids would say, "Look, here comes one of Charlie's kids, and he's wearing so-and-so's old shirt." Or shoes, or pants, or whatever I was wearing that day.

It was at those times that I wished my dad hadn't told me about the hate demon. I could feel him growing in me as I fed him. It all worked itself out, though. Eventually, they stopped making fun of my siblings and me. After a few bloody noses, courtesy of the hate monster, and myself of course.

#

It was during those years in the bar with my father that I learned the meaning of what would later be called "work ethic." I also learned a lot about humanity. As I grew up, I watched the same people who laughed and joked with my father have a few drinks and turn mean. For example. My dad always stayed at the end of the bar nearest the kitchen, and the beer tap. That way if someone ordered food or drink, he was right there. Some of these "men" would start off sitting at that end of the bar. After a few drinks, they would move to the other end of the bar, as far away from my father as they could get. Usually, one of them would order a beer, watch my father fill the glass from the tap, and bring it back to him. As soon as he walked back to the other end of the bar, the other one would say, "Hey Charlie, how about a refill?"

And so, the game would go. If my father stayed at that end of the bar, they would move to the other end. To them, it was a game, to my dad it was agony. I saw the pain on my dad's face as he limped the 30 feet from one end of the bar to another, and 30 feet back again. I also saw the look of determination. The stubborn set his jaw would have whenever he faced a challenge. That tenacious, persevering, persistent, pig-headed expression of a focused man of Sicilian descent. It was this same mindset that enabled my father to accomplish the things that people told him he couldn't do.

My dad may have been forgiving of those men, but I wasn't. In retaliation, I would key the paint on the cars of the men who were mean to my dad, along one or both sides. If I were pissed off enough, they'd get a flat tire or two. If the mean men didn't have a car, I would remember who they were. Sooner or later they would order a sandwich, and I would run to the kitchen to make it. Once there, I would decide if I would use spit or snot as a condiment.

Yes, I got my revenge, but I never really hated those men. They weren't worth the cost of feeding the monster inside me. Instead, I felt sorry that they would never know the man that I knew and loved. The man that lived in pain every day, so that his children would have a better life. A disabled man that, except for the grace of God, they might have been.

#

When I was twelve-years-old, my parents divorced. Two of my brothers and I stayed with my father. My sister and the two youngest brothers went to live with my mother. The court awarded her $30 a week in child support, half of my father's income. My two brothers and I all got part-time jobs to help supplement our father's income. Charlie's family did nothing to help us.

At age sixteen and a half, I joined the military. My father had to sign for me to go, which he reluctantly did. My plan was to be deployed to Vietnam because Uncle Sam paid more for battlefield assignments. I was fortunate in that I never saw combat.

While I was in the military, I sent every penny home that I could, hoping to make things a little more comfortable for my dad and brothers. When Uncle Sam discharged me, I was twenty-one years old, and my father was 50. When I walked through the door of my father's apartment, the smile faded from my face as I stopped in my tracks. Those four years had changed my dad. He was no longer the dark-haired, barrel-chested, and high-spirited man I remembered. All those years of working seven days a week at the bar had taken their toll.

My father's hair had turned white, and his back had given out, but he still went to work every day. He wore a back brace and walked the bar doubled over with the aid of a cane. The fire was no longer in his eyes, and for the first time, I heard the tiredness in my dad's voice when he spoke. As I sat across the table from my father, my heart sank, and I struggled to hold back the tears. It had suddenly dawned on me that my father was mortal. There was even some part of me that knew my dad wouldn't be with us too much longer.

That same afternoon I begged my dad to quit his job and let his sons help him, as he had supported them. He wouldn't hear of it. "You and your brothers should make your own lives, he told me. Get married and give me grandchildren to play with." He insisted that he would be okay, and he became adamant about it. The set of his jaw told me there would be no compromise.

I didn't understand why then, but I do now. My father needed to have a purpose, a reason to keep going. That, and his pride would not let him accept what we had so often heard him call a "handout."

Pride is indeed a double-edged sword.

#

At the age of twenty-two, I married my first wife and was hired by "The Phone Company." Ten months later my wife presented my father with his first granddaughter. A little over a year after that, at age 52, Charlie passed away. It was just three months after our daughter had died. I was devastated for the second time. My oak tree had fallen.

It was at my dad's funeral where I learned things about my father that I had never known. They were things he could have bragged about but never did. One man told us that my dad had been the assistant manager of the Orpheum Theater in Jersey City, New Jersey. He showed us pictures of my father posing with famous people. We also found out that before working for his brothers at the bar, my father was a well-paid master diesel mechanic. He had lost his job because the other workers told the foreman having a cripple around disturbed them, and they couldn't focus on their work.

Things are different these days. People with disabilities can do the things my dad could only dream of doing. No one calls them a cripple anymore, and they can get a decent paying job almost anywhere.

Many people came up to us as my brothers and I sat together at my father's casket. A few people told us how he had helped them through difficult times. Some said my father had convinced them to stop drinking and they had turned their life around. Others stated that my dad would lend a sympathetic ear when they were going through a tough time in their life. It was his advice and support that had helped them get through it. To those people he was not "Charlie the Cripple," he was Charlie, their friend.

#

On the day my father was put into the ground, we were all gathered together at his apartment to pay tribute to him. Two of his brothers, who owned the bar, were lamenting the fact that they wouldn't be able to find anyone to take his place. They looked at me as if to say, "What about you?"

The anger rose in me, as I sat across from them at the table. The anger I had been holding in my whole life. You good for nothing, brother killing bastards, I thought. It's because of you that my father died so young, you fuc*ing bastards worked him to death! My combat training kicked in; it was all muscle memory. I looked from one uncle to the other. Which one would die first? The killing sequence scrolled through my mind, like a set of instructions, just as my instructors taught me.

As above so below. The mind controls the body. The switchblade clicked open under the table, and my body started to react to the images in my mind. I'd made my decision, Orlando, the one who hurt my father the most, would be the first to die.

As I began to rise, my dad's pet cat, Skippy, jumped onto my lap. She looked at me with such a sad expression that all of the hatred drained from me. Love for this little creature who had loved my father unconditionally replaced it. Skippy missed my father too. While tending to the cat's needs, my anger faded away. Luckily for my uncles, the hate monster didn't get to eat that day.

#

My father told me once that, according to Sicilian legend, when a person dies, they can "call" someone to be with them on the other side. I don't know if that's true, I only know that within a year of Charlie's death all three of the bar owners were also dead.

Orlando was the first to go. Quick with his temper and his fists, he died of a heart attack at the gym. This, the day after a complete physical found he was in perfect health. The next brother died a few months later, and the third a few months after that. Call it karma or whatever you want; I didn't attend any of their funerals.

My only regret is that my dad didn't live long enough to see all of his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren become the successful people they are today. More successful even than those of his brothers.

I have faced many challenges in my life, but none of them were as challenging as the ones my father met. Thanks to the values my dad instilled in me, I have survived them all. Each time I encountered a particularly daunting task or felt that I'd been given more than I could handle, I'd picture my father. That stubborn look of determination on his face would say to me. "You promised me you would do better. If I could endure, so can you."

Charlie may not have been a hero to the rest of the world, but he was to me.

That's why I wrote this.

By the gods, I miss that man.

The End

Photo Credit: Disability History Museum

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://therelationshipblogger.com/charlie/