Emotionally saturated experiences contribute to the consolidation of memories of minor previous events and stimuli that would have been forgotten without these experiences. American scientists have shown that such a retrospective consolidation of memories is selective. Not all the details of recent experience are memorized, but only related in terms of the circumstances of the subsequent emotional experience. The results obtained are consistent with the "synaptic label" hypothesis, proposed in 1997 to explain the fundamental mechanisms of memory.

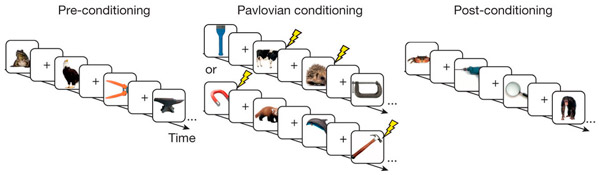

Fig. 1. The scheme of the experiment. In the first phase of training (Pre-conditioning), the subject is shown in a random order the images of animals and instruments. The subject must sort the pictures into these two categories. In the second phase (Pavlovian conditioning), when a picture of one of the categories (either animals or instruments) is shown, the subject receives a slight electric shock. The third phase (Post-conditioning) repeats the first. Sets of pictures are used differently each time.

Over the past 20-30 years, neuroscientists have made tremendous progress in deciphering the mechanisms of memory (see links at the end of the news). However, there are still many unresolved issues. One of the most important tasks is to test the hypothesis of "synaptic tags", proposed in 1997 by Frey and Morris (U. Frey & R. G. M. Morris, 1997. Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation). The hypothesis explains the mechanism of formation of long-term memory (see Long-term potency). Simply put, memory is the amplification or relaxation of certain synaptic contacts between neurons. Short-term memory is based on transient changes in synapse strength (Synaptic strength), which occur when it is briefly excited and does not require protein synthesis. Such changes may be related, for example, to the phosphorylation of already existing proteins and to a change in their conformation. To fix (consolidate) the ephemeral memory, a steady change in the strength of the synapse is necessary. For this, new proteins must be synthesized in the nerve end (dendritic spine or axon terminus). The production of these proteins is triggered by a sufficiently strong and prolonged excitation of the neuron.

The problem here is that the mRNA required for the synthesis of proteins is produced in the nucleus of the neuron, and there may be thousands of endings and synapses in each nerve cell. From where do mRNAs (or proteins synthesized on their basis) "know" to which of the hundreds of dendritic spines they need to go to provide long-term potentiation? Frey and Morris suggested that in synapses with temporarily increased conductivity, certain biochemical "tags" are formed, and the production of new proteins is not required for this. These labels, which last no more than 2-3 hours, help to capture the desired mRNA (if the neuron starts producing them within the specified time) and use it to synthesize the protein in this dendritic spine. As a result, the postsynaptic membranes located on this spinule undergo a long-term potentiation: the memory from the ephemeral becomes stable.

From the hypothesis of synaptic labels follows a number of verifiable consequences. For example, it implies that if a neuron has "tagged" synapses, then the long-term potentiation at these synapses can form not only in response to a repeated signal transmission through the same synapses, but also in response to signals received by a neuron through other synapses . In other words, the transient memories of some non-essential events that would normally be forgotten soon can be written into long-term memory if the corresponding neurons are strongly excited for two or three hours after these events on any other occasion.

Indirect confirmation of this prediction was obtained in behavioral experiments in rats. It turned out that if rats teach a little something to one, and after a short while to intensively teach something to another, but necessarily new to the rat, then the first skill that would normally be forgotten is retained for a long time. This phenomenon was called "behavioral tagging" (behavioral tagging: see F. Ballarini et al., 2009. Behavioral tagging is a general mechanism of long-term memory formation. In addition, it is known that strong emotions in people sometimes contribute to remembering many small and seemingly insignificant events and details of the environment, perceived shortly before a strong experience. This may be a consequence of the mechanism of "synaptic tags." However, the existence of "behavioral labeling" in people has not been strictly considered.

A new study by neurobiologists from New York University and from the Nathan Klein Institute for Psychiatric Research, the results of which are published on the website of the journal Nature, added a number of significant details to the existing picture. First, the authors convincingly showed that "behavioral labeling" is characteristic not only of rats, but also of humans. Secondly (and this is the main thing), they demonstrated the selectivity of the retroactive (directed from the present to the past) fixing the memory of recent events with subsequent experiences. From the hypothesis of synaptic labels it follows that the consolidation of memories should be facilitated by the subsequent excitation of not any neurons, namely those that have marked synapses. Accordingly, we can expect that the subsequent experience should fix the memory of nothing, but only that one way or another associates with this experience (and therefore causes the excitation of the same populations of neurons).

In the experiment, 119 volunteers participated. Each of them first performed three tasks (Figure 1), and then passed a memory test. The first task was that the person was shown in random order the images of animals and instruments (30 of those and others), and he had to divide the pictures into two thematic groups. Subjects did not know that the subject of study is memory; remember the pictures of them no one asked. Tools and animals were chosen for the reason that, as previous studies have shown, the processing of information related to these two categories involves different parts of the cortex. Some groups of neurons in the occipital-temporal region are excited at the sight of instruments or memories of them, but do not respond to demonstration of animals, and vice versa. Accordingly, it can be expected that the experiences associated with animals will interact with synaptic marks associated with them, but not with tools.

Then another series of 60 images of guns and animals was demonstrated. This time, electrodes were attached to the subject and, with a probability of 2/3, beat him lightly with an electric current when an image of one of two categories appeared. The "task" was now to anticipate the electric shock, but it was only for a divorce. In fact, the authors conducted the development of the classical (Pavlovian) conditioned fear fear, accustoming some subjects to worry at the sight of pictures with animals, and others - at the sight of pictures with instruments. Reflexes in the subjects really worked out. This was confirmed by measurements of the electrical conductivity of the skin: it increased in the "trained" subjects at the sight of pictures of the category with which they associated the expectation of electric shock (CS +), but not the one that was safe for them (CS-). Finally, the third task, performed immediately after the first two (intervals between tasks did not exceed 5 minutes), was a repetition of the first. All the pictures were new again, not used in the first two tasks.

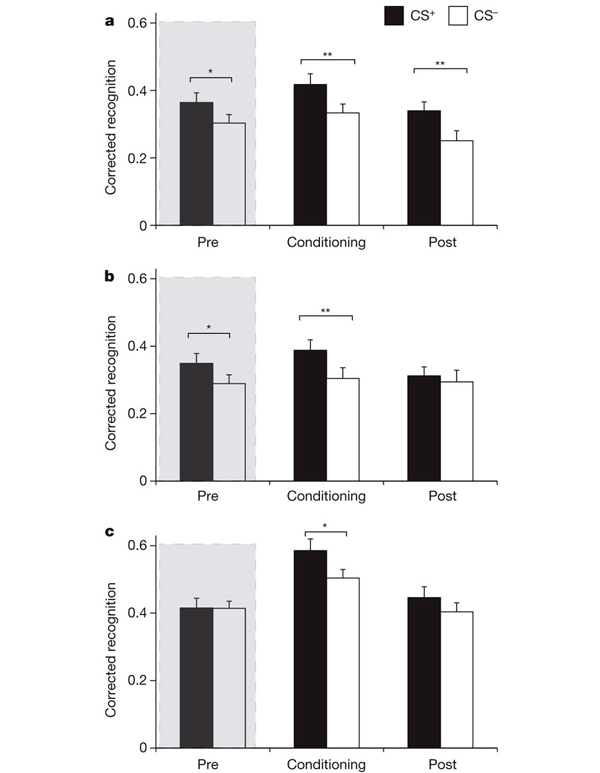

Then the authors checked how many pictures each participant remembered. Recall that the test for memorization was a surprise for the subjects: they were not warned that remembering pictures matters. Participants were randomly divided into three groups. The first group was tested immediately after the third task, the second one - the same day after 6 hours, the third - after 24 hours. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Memorization of the pictures by the subjects depending on the category of the picture (black bars - the category on which the conditioned reflex of fear was developed), the testing phase, on which the subject saw the picture (Pre - the first task, conducted before the experiments with electric shocks, Conditioning - the second task , when pictures of one of the categories were accompanied by unpleasant sensations, Post - the third task, conducted last and in its design repeated the first one), and the time elapsed between performing tasks and checking the memory (a - 24 hours, b - 6 hours , C - 0 hours).

References for Text and Images:

- https://currentmedicalresearch.wordpress.com/basic-info/other/what-are-dreams/

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/feb/08/total-recall-the-people-who-never-forget

- http://www.like2do.com/learn?s=Emotional_memory

- http://susankriegler.blogspot.in/2015/08/unlocking-emotional-brain.html

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/12/141203084059.htm

Support @steemstem and the #steemstem

project - curating and supporting quality STEM

related content on Steemit

the beauty of science.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

cool

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit