Today I've got a wireless mouse to take apart and explain. I got this useful little device on an Ebay auction for a few bucks.

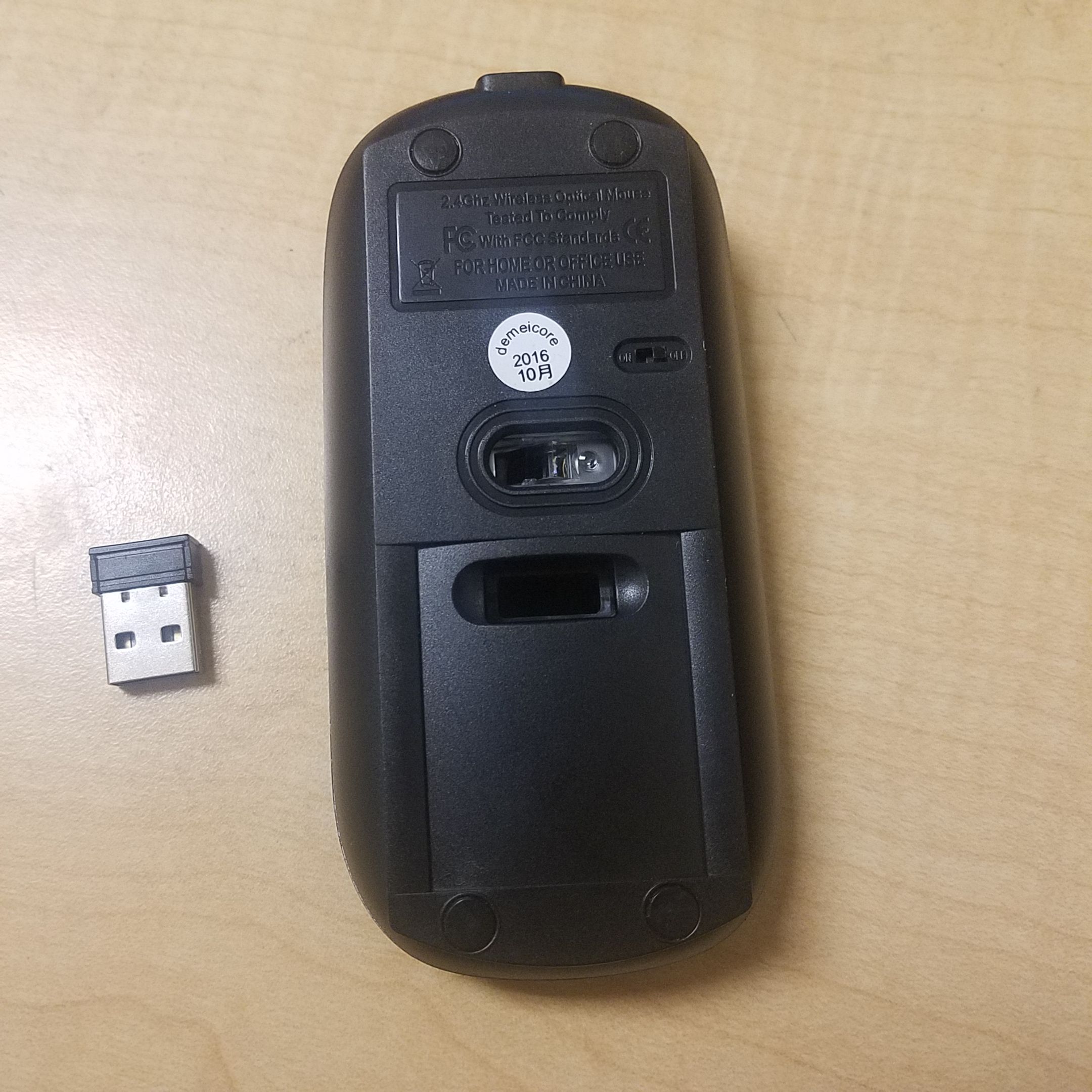

As the name implies, this computer mouse can be used to click on things without any connecting wires. A tiny USB receiver plugs into a computer to receive and send signals to the mouse. Of course, an onboard battery within the mouse allows it to power itself, since sending wireless power would be quite difficult. Here's the mouse in its intact state:

Let's take a look inside.

Getting inside the mouse

Surprisingly, there were no screws on the outside of the device. I thought that they were hidden under the rubber feet, but happily found out that you can actually take this device apart without a screwdriver. The two click-pads pull right off, revealing a second internal plastic shell:

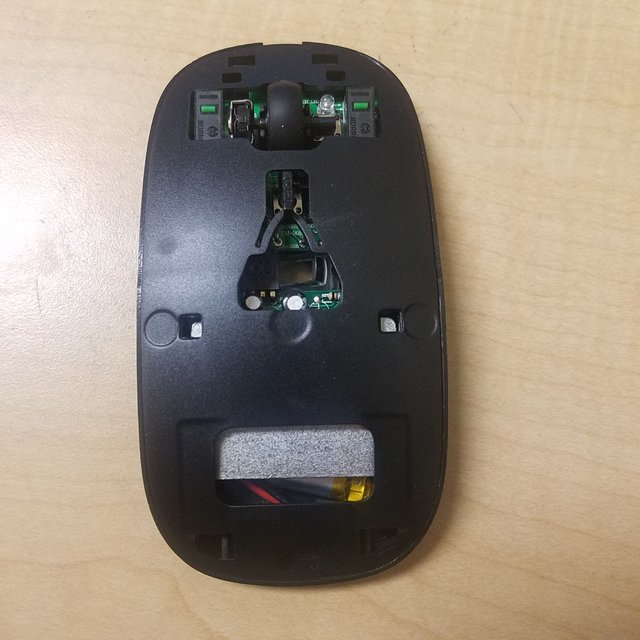

Immediately you will notice two large buttons (to tell the computer when you've clicked on something) and a strange metallic plate. This piece of metal intrigued me, and I immediately thought it was some sort of heatsink or even a RF shield. However, neither of these items make sense: A heatsink would be totally unnecessary for such a low-power device, and there would be no need to shield any of the components in a simple wireless mouse. To get to the metal chunk, I peeled off the second plastic shell (which also had no screws!) with a flathead screwdriver and it snapped right out with very little damage. Now it is easy to see the true purpose of the mysterious metal piece, along with the mouse's internal circuitry:

It's finding stuff like this that really makes opening up electronics fun. You would have never known this was in here without opening up the mouse. As you can clearly see, the piece of metal does absolutely nothing. It appears to be a thick (>5 mm) chunk of solid aluminum, clamped to the outer plastic frame by a single screw and washer. I unscrewed the chunk to see if anything was underneath to no avail.

The aluminum has no actual purpose. It simply lies above the main circuit board, stuck to the plastic. The reason it's there? Marketing, at least indirectly. This piece of useless metal makes the mouse feel physically heavier, which for some reason makes people think that the mouse is higher quality than it actually is. I'm not sure who was expecting an incredibly high quality mouse for $5, or who was expecting a high-quality mouse to actually be heavy when it doesn't need to be, but apparently the factory in China decided that this was the best use for some spare chunks of aluminum. Interesting that it's there, nonetheless.

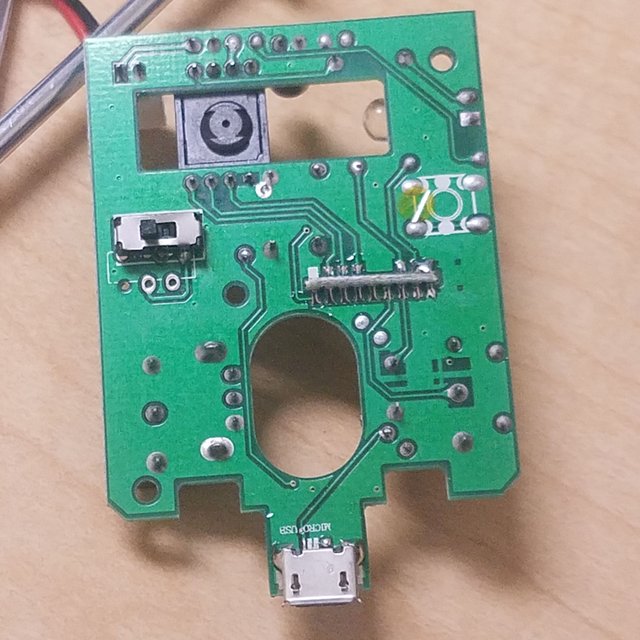

Anyway, back to the actual circuit. As you can see on the above image, we have a small lithium-polymer battery connected to a single green PCB containing all of the electronics. Let's take a closer look...

Detector Circuitry

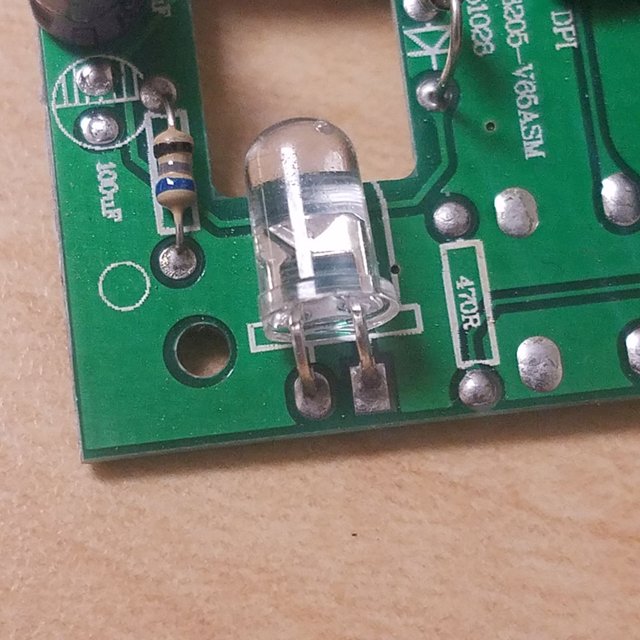

As you surely know, the bottom of a computer mouse contains a set of optical lenses that emit red light when the mouse is turned on and used. This light is sourced from a rather large red LED, shown below:

The gap in the PCB allows light to escape the mouse

Nicely enough, it appears that the manufacturer was kind enough to label most of the component values! A nice plus if you are looking to repair your mouse.

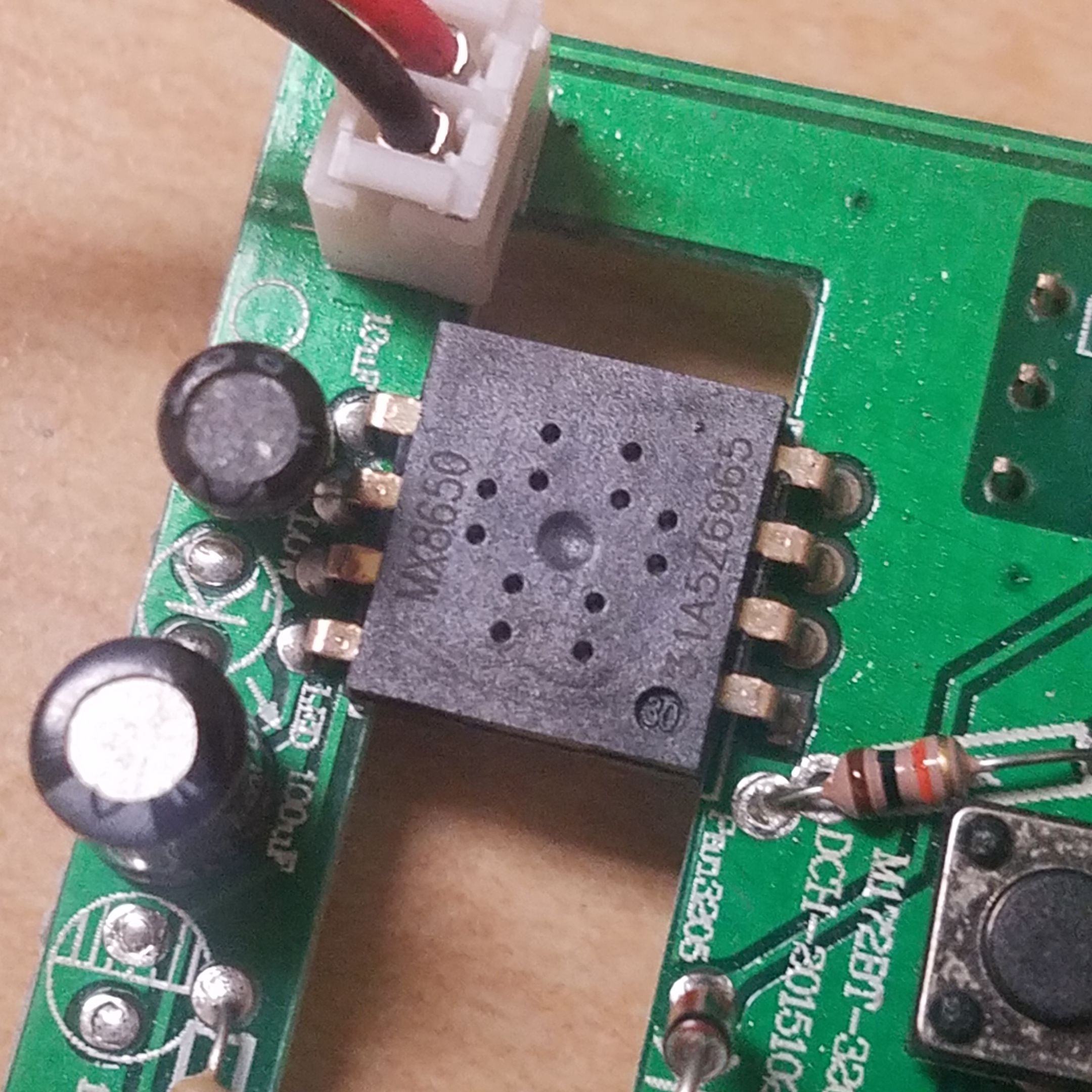

Just across the PCB gap lies a black box that looks like a speaker. The underside looks like a laser diode, with a tiny pinhole opening for detecting something. That "something" is light: This device is known as the MX6850 (Datasheet), and serves as a 2-dimensional motion detector. This sensor is what tells your mouse where to place the pointer on the screen, and is powered by the battery. This in conjunction with the red LED shown previously is what lets your mouse detect where is it on the table, and in turn figure out what part of the screen it is clicking on.

MX8650 Optical Sensor. Above and to the left is visible a removable battery connector. I was quite surprised that the battery was not directly soldered to the board, but this connector would make it pretty easy to add a much larger battery to the mouse.

Flipping the board over reveals the business end of the MX8650.

Charging and Power

The other side of the board (accessible by removing a single easy to reach screw) reveals a few additional parts. At the top, the sensor opening of the MX8650 is visible (taping over this would make the mouse cease to function). All that is left on this side of the board is a metal on/off switch and a steel microUSB charging port. This allows you to charge the battery directly from your computer, using the integrated charging circuitry.

Once the device is plugged in through this port, the battery can be charged. The battery itself is a lithium-polymer cell, which is pretty small but perfectly adequate for a mouse like this. Unfortunately no energy/mAhr rating is visible on the cell, but the voltage is going to be around 3.7 Volts nominal. At the front of the cell, the typical charge protection circuitry is visible. This battery is charged through the white connector from before and can be used to run the mouse for hours without any wires.

The surface-mount resistors and capacitors at the top are part of the protection circuitry. The orange sticky tape is kapton tape, a special tape that keeps its properties for a range of temperatures, making it useful for stuff like 3D printer heated beds and spacecraft.

Radio Transmitter

But of course, this mouse still needs to be wireless. One last subsystem handles this. Without a way to tirelessly communicate with the computer, the mouse will need to be wired up to the USB port. This problem is solved by an onboard 2.4 GHz microwave transmitter. 2.4 GHz, if you remember, is the same frequency used in microwave ovens, WiFi connections, and Bluetooth (+- a few megahertz).

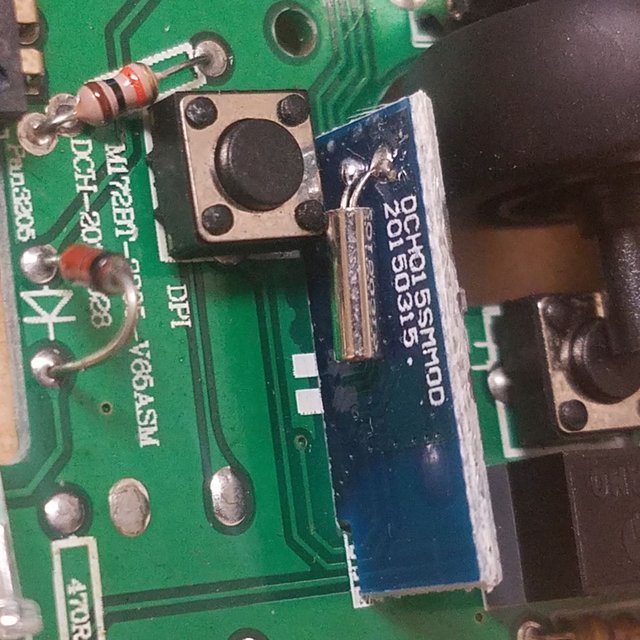

On the mouse's board is a small, additional blue PCB that has been shoved vertically into the green board and soldered into place. This board contains a metal crystal oscillator. Crystal oscillators, as I covered in my AM radio post, are essentially piezoelectric crystals that oscillate at a very specific frequency, usually several megahertz. While this crystal could be being used to generate the 2.4 GHz oscillation directly, I have a feeling that it's just being used as part of the remaining oscillator circuit, maybe as a way to keep the frequency precisely on target.

Blue 2.4 GHz oscillator/transmitter board. The metal can is the crystal oscillator. You can also see a resistor and diode off to the side.

Unfortunately I've been unable to dig any information on this board. The circuitry on the opposite side, containing the actual oscillator, is covered by a black hardened paste, making it impossible to view what is going on. Regardless of what we can see, this small blue PCB is generating an electrical oscillating wave at 2.4 GHz frequency, the directing it to an antenna to radiate away 2.4 GHz microwaves.

But the computer needs a way to receive these electromagnetic waves so that it can communicate with the mouse. This can't be done via wifi (a much more expensive wifi chip would be necessary), and the mouse (despite being falsely advertised as such) doesn't have a bluetooth module. Instead, a secondary receiver is used: The USB receiver. This little device fits into the back of the mouse, to be removed when the mouse is in use. Plug the USB device into any computer USB port, and it acts as a radio receiver for the 2.4 GHz radiation produced by the mouse. Powered by the computer directly, this USB receiver can then receive electromagnetic signals from the mouse, allowing you to interact with your desktop wirelessly.

Unfortunately, taking apart the USB receiver would destroy it, and I still intend to use this mouse so I am unable to show you the insides. Don't be too disappointed though - I've done it before, and it's not that interesting. They typically just contain a small 2.4 GHz zigzag antenna and a bunch of tiny, covered-up circuitry that I can't really interact with. I suppose there could also be a transmitter onboard, but I doubt it - this USB receiver should only need to receive signals from the mouse, not send them back.

That's about it for this mouse: A strange little fusion of optics and radio technology in a tiny, cheap, everyday package. I hope you learned something new and found this teardown interesting. Thankfully for me, the mouse was really easy to re-assemble and I am able to use it even after getting to almost every part. I should have covered every subsystem of this device.

I'm kind of interested in what that crystal oscillator is doing. I know you can get GHz range crystal oscillators, but one in that form factor is something I haven't seen. I may buy the next $2 one I see at the dollar store and see if there are any high frequency signal generators on campus to try it out, single the oscillator isn't labelled.

Let me know if you have any questions or comments, or if I made a mistake here. I'll try to respond as fast as possible to any questions.

Thanks for reading!

All images in this post are my own. You are welcome to use them with credit.

Nicely executed wireless mouse is smothing really beneficial gadget and thanks for sharing .

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I have a wireless mouse from A4Tech. Recently it started occurring problems. I was thinking about tearing it down. your post helped me @proteus-h

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Being A SteemStem Member

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit